Compounder Fund: Markel Investment Thesis - 22 Apr 2021

Data as of 20 April 2021

Markel (NYSE: MKL), which is based and listed in the USA, is one of the 40 companies in Compounder Fund’s initial portfolio. This article describes our investment thesis for the company.

Company description

Markel has three key economic engines in its business: It markets and underwrites insurance products; it invests the premiums and profits from its insurance operations into stocks and bonds; and it acquires full or majority stakes in privately-held companies from a wide range of industries.

Under its insurance arm, Markel focuses on specialty insurance products. The standard insurance markets deal with relatively predictable exposures while the products and coverages that are offered by different insurance companies tend to be similar; as a result, insurance companies in the standard markets tend to compete based on price. Examples of standard insurance products that are common for individuals in Singapore would be life insurance plans and hospitalisation plans.

Specialty insurance, on the other hand, deals with insurance coverage for unique risks and as a result, has a lesser focus on price. To generate good business returns with specialty insurance products requires an insurer to develop expertise in niches. Some examples of niches that Markel has targeted include: liability coverage for highly specialized professionals (such as architects, engineers, lawyers, doctors, dentists and more); wind and earthquake-exposed commercial properties; equine-related risks (risks faced by horse farms); and classic cars.

Markel’s insurance arm is also involved with reinsurance, where Markel insures other insurance companies. There are times when an insurance company needs to purchase insurance products to manage its own exposure to risks – this is where Markel’s reinsurance operations come into play.

Under its investing arm, Markel invests the insurance premiums it collects from its clients into high-quality government, municipal, and corporate bonds. Markel also invests the profits from its insurance arm (premiums are not profits – profits are what’s left from premiums after insurance claims and expenses are paid) into stocks.

The business unit where Markel acquires full or majority stakes in privately-held companies from a wide range of industries is called Markel Ventures. There are more than 20 companies in Markel Ventures and they are from outside the specialty insurance market. Some of the companies are: Brahmin (creates leather handbags); CapTech (technology consulting firm for businesses); Costa Farms (largest producer of ornamental plants in the world); Cottrell (designs and manufactures on-road transportation equipment for road vehicles); Diamond Healthcare Corporation (provides behavioural health services); Havco (designs and manufactures wood floorings for truck trailers and containers); Reading Bakery Systems (designs and manufactures industrial baking systems); and RetailData (provides retail intelligence).

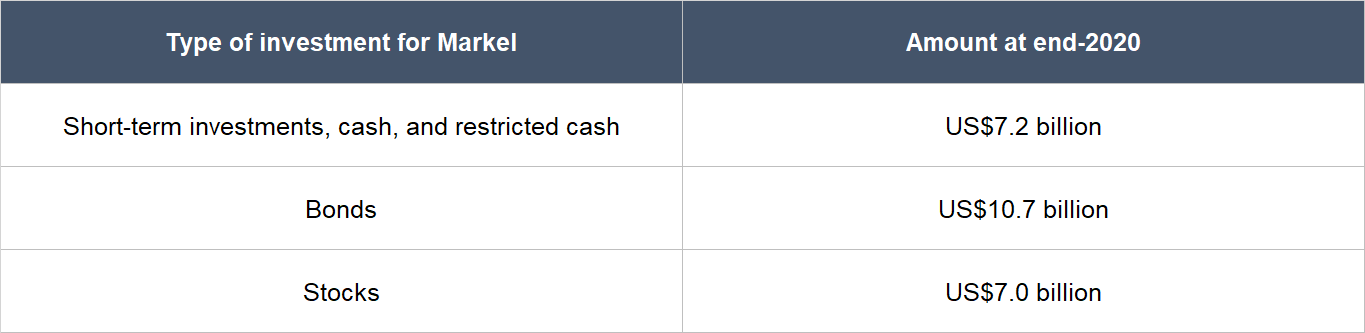

Markel enjoyed earned premiums (the revenue of its insurance arm) of US$5.61 billion in 2020 while Markel Ventures generated total revenue of US$2.79 billion. The company also ended 2020 with US$41.7 billion in total assets, of which US$24.9 billion are in the form of cash and equivalents, stocks, and bonds (see table below for a breakdown). In contrast, Markel Ventures only accounted for US$3.64 billion (8.7%) of Markel’s total assets. So from both revenue and asset perspectives, Markel’s more heavily tilted toward insurance/investing rather than Markel Ventures.

Source: Markel annual report

In terms of geographic exposure, Markel’s a US-centric company. In 2020, 79% of the company’s total underwritten gross premiums of US$7.2 billion came from the USA. (Gross premiums are the total premiums Markel collects before it deducts certain expenses and transfers some risk to other insurers – what’s left is effectively known as earned premiums.) Meanwhile, the USA accounted for 95% of Markel Ventures’ revenue in the same year.

Earlier, we mentioned that Markel’s insurance arm is focused on speciality insurance products. Here’s more colour: 84% of Markel’s total underwritten gross premiums of US$7.2 billion in 2020 came from its specialty insurance products while the remaining 16% was from reinsurance products.

Investment thesis

We have laid out our investment framework in Compounder Fund’s website. We will use the framework to describe our investment thesis for Markel.

1. Revenues that are small in relation to a large and/or growing market, or revenues that are large in a fast-growing market

We think that there’s still plenty of room for Markel to grow. Let’s start with its insurance arm.

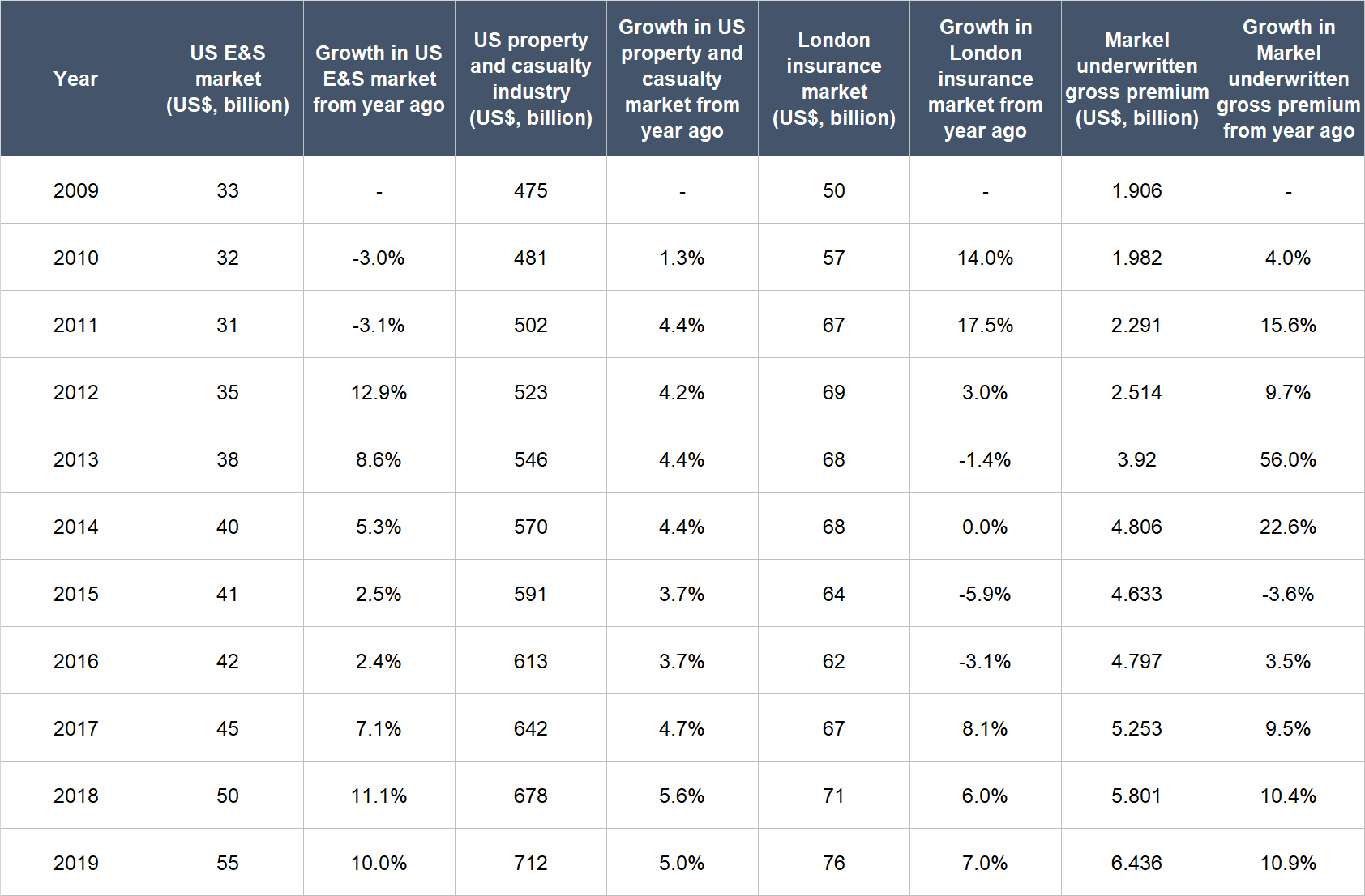

As we had already mentioned, Markel’s focus is on specialty insurance, which is also known as excess and surplus lines (E&S). The E&S market in the USA was US$55 billion in 2019, or around 8% of the entire US$712 billion US property and casualty insurance industry. For perspective, Markel’s total underwritten gross premiums in 2020 – which includes premiums from beyond the USA – was US$7.2 billion. Outside of the USA, Markel participates in the London insurance and reinsurance market, which produced US$76 billion of gross written premiums in 2019; Markel’s share of the London market in the same year was merely 2%. Markel also participates in the US$71 billion Bermuda insurance and reinsurance market and had a market share of just 1% in 2018.

The table below shows the growth over the last decade of the various insurance markets mentioned above along with Markel’s total underwritten gross premiums. Two things to highlight here: (1) Markel’s insurance markets are growing, albeit slowly; and (2) Markel’s total underwritten gross premiums had generally grown faster than its markets, which indicates that the company had been winning market share for a long time. More market share gains for Markel could be on the way. The company recently unveiled its “10-5-1” goal, where it aims to reach US$10 billion in earned premiums in five years (up from US$5.61 billion in 2020) and earn US$1 billion in underwriting profit.

Source: Markel annual reports

Let’s now move to Markel’s investing arm and Markel Ventures. Markel’s stock market portfolio is heavy in US-listed stocks and Markel Ventures derives nearly all its revenue from the USA. Markel’s primary focus in the stock market and in acquisitions for Markel Ventures are on finding great companies and owning them for the long run (more on this later). We think these traits put Markel’s investment portfolio and Markel Ventures in a good position to ride on the USA’s long-term economic growth. We recognise that the US economy is not going to deliver fast growth due to its sheer size – it is currently the world’s largest economy – but we’re still optimistic about its long-term prospects. In his 2018 Berkshire Hathaway shareholders’ letter, Warren Buffett wrote:

“Charlie and I happily acknowledge that much of Berkshire’s success has simply been a product of what I think should be called The American Tailwind. It is beyond arrogance for American businesses or individuals to boast that they have “done it alone.” The tidy rows of simple white crosses at Normandy should shame those who make such claims.

There are also many other countries around the world that have bright futures. About that, we should rejoice: Americans will be both more prosperous and safer if all nations thrive. At Berkshire, we hope to invest significant sums across borders.

Over the next 77 years, however, the major source of our gains will almost certainly be provided by The American Tailwind. We are lucky – gloriously lucky – to have that force at our back.”

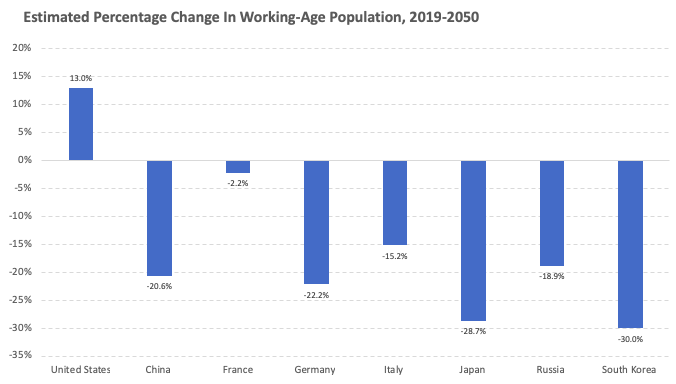

To build on Buffett’s American Tailwind idea, we want to highlight that the working-age population in the USA is estimated to increase by 13% from today to 2050. This is one of the healthiest demographics among developed nations across the world and could be an important driver for the growth of the US economy in the long run. Here’s a chart from venture capitalist Morgan Housel showing this:

2. A strong balance sheet with minimal or a reasonable amount of debt

Since Markel is primarily an insurance company, we’re focusing on its total assets and shareholders’ equity to assess the strength of its balance sheet. In particular, we’re looking at the leverage ratio, which is the ratio of total assets to shareholders’ equity. The lower the leverage ratio, the higher the percentage of an insurer’s assets that is being funded directly by shareholders’ equity, and the sturdier its balance sheet.

At the end of 2020, Markel had total assets of US$41.71 billion and shareholders’ equity of US$12.80 billion, which gives a leverage ratio of just 3.25. We think this is a healthy leverage ratio.

3. A management team with integrity, capability, and an innovative mindset

On integrity

Markel’s top two leaders are its Co-CEOs, Thomas Gayner and Richard Whitt, III. Gayner, 59, was appointed as Markel’s Co-CEO in January 2016 and has been with the company since 1990. He has played – and is still playing – a major role in Markel’s investment process and operations since his employment with the company began. Prior to being Co-CEO, Gayner’s title from May 2010 to December 2015 was Chief Investment Officer. Meanwhile, Whitt, 57, was appointed as Co-CEO at the same time as Gayner. He is also a long-tenured Markel employee, having joined the company in 1991. Whitt was previously Markel’s chief operating officer from May 2010 to December 2015 and is currently leading the charge for Markel’s insurance activities.

We appreciate Gayner and Whitt’s long tenures with Markel and relatively young ages. The fact that Markel promoted two long-time employees to become Co-CEOs also speaks positively to the company’s culture, in our view.

Markel’s compensation structure for its key leaders is one of the best we’ve seen among public-listed companies we’ve studied and we think this highlights the integrity of the management team. The key points:

- Gayner had a base salary of US$1 million in 2020. For the year, he could also earn RSUs (restricted stock units) and cash awards. The RSUs typically vest over a three-year period.

- The amount of RSUs and cash awards Gayner could earn would be a certain percentage of his base salary. This percentage, in turn, is determined by the compound annual growth rates (CAGRs) for Markel’s book value per share and share price for the five years ended 31 December 2020.

- For annualised growth rates of between 0% and 16% for Markel’s book value per share and share price, the amount of RSUs and cash awards could be between 0%-600% and 0%-300%, respectively, of Gayner’s base salary. For growth rates of 17% or more for the two financial measures, Markel’s directors have full discretion to determine the percentage of Gayner’s base salary that his RSUs and cash awards are.

- Markel’s actual CAGRs for its book value per share and share price for the five years ended 31 December 2020 were 10% and 3%, respectively. This resulted in Gayner earning RSUs and cash awards in 2020 that were 210% (US$2.1 million) and 105% (US$1.05 million), respectively, of his base salary for the year.

- In all, Gayner’s total compensation for 2020 was US$4.18 million, comprising his base salary of US$1 million, RSUs of US$2.1 million, cash awards of US$1.05 million, and other compensation of US$33,420. This means that 75% of Gayner’s overall compensation in 2020 came from his RSUs and cash awards.

- Whitt’s total compensation for 2020 was identical to Gayner’s in both structure and amounts except for one tiny difference: Whitt’s other compensation was US$27,972 instead of US$33,420.

We do note that there’s no skin in the game for Markel’s Co-CEOs. As of 2 March 2021, Gayner and Whitt collectively controlled just 32,405 Markel shares. At the company’s 20 April 2021 share price of US$1,197, their shares are worth only US$38.8 million. But this lack of meaningful ownership is nowhere near being a dealbreaker when we consider Gayner and Whitt’s well-crafted compensation structure at Markel.

On capability and innovation

We rate Gayner, Whitt, and their team highly on this front and there are a few things we want to discuss. These things include Markel’s business and financial data that stretch back to 2007 or earlier. Although Gayner and Whitt only became Co-CEOs in January 2016, they both have been in important leadership roles at the company for a much longer period of time. So the fingerprints of Gayner and Whitt definitely can be found on the good work that Markel has accomplished over the years.

The first thing we want to discuss is Markel’s excellent culture in risk management in its insurance business. Markel’s investing arm has two portfolios: A portfolio of stocks, and a portfolio of high-quality government, municipal, and corporate bonds. The bonds generally have durations (the times taken for the bonds to mature) and currencies that match those of Markel’s insurance policies (duration, when applied to the context of insurance, is the amount of expected time that exists between underwriting insurance policies and expecting clients to make claims on the policies). This is important from a risk-management perspective beecause an insurance company with mismatches in duration and currencies between its investment portfolio and insurance products is at higher risk of running into financial problems.

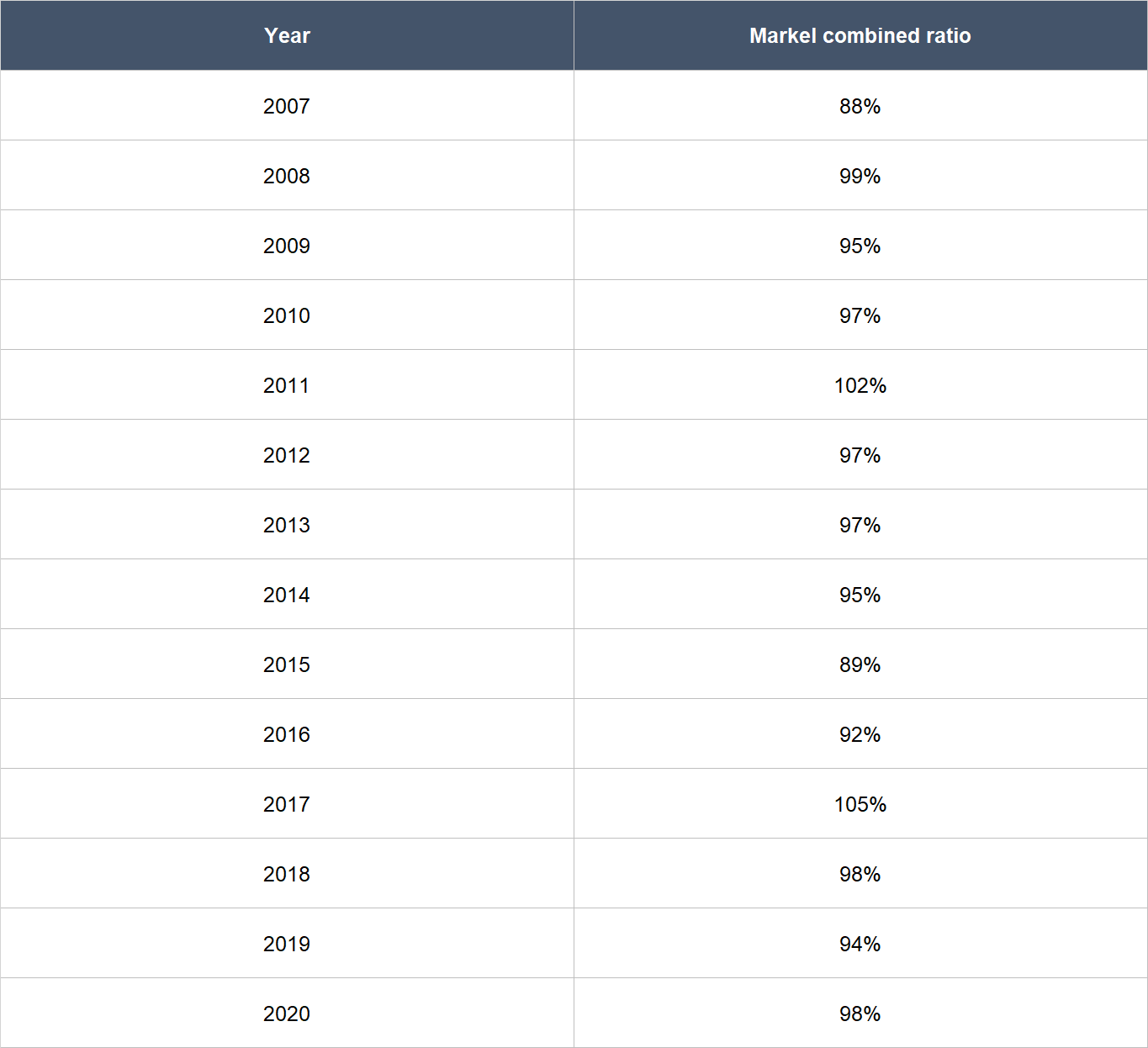

In addition to matching the duration and currencies of its bond investments portfolio with its insurance policies, there is Markel’s combined ratio. An insurer with a combined ratio of less than 100% is making a profit from the policies it has underwritten. A combined ratio of more than 100%, on the other hand, means that the insurer is making a loss on its policies. If an insurer has a history of regularly producing a combined ratio of more than 100%, there’s a strong possibility that the insurer’s leadership team has a poor approach to risk management. Consequently, the lower the combined ratio, the better.

The table below shows Markel’s combined ratio from 2007 to 2020 (we chose 2007 as the starting point to observe how the company fared during the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis). During the period, Markel’s average combined ratio was 96% and only exceeded 100% in two years (2011 and 2017). This is an excellent long-term track record of profitable insurance underwriting.

Source: Markel annual reports

In particular, Markel’s combined ratio of 98% in 2020 is worth highlighting in a positive way. 2020 is well-known now to be the year of COVID-19 and the pandemic alone accounted for six percentage points of Markel’s combined ratio of 98% for the year, largely because the company had underwritten insurance policies for event cancellations and business interruptions. But what’s perhaps less well-known about 2020 is that it was also a year of above-average levels of weather-related disasters, thus compounding the misery for insurance companies. Given the difficulties faced by Markel in 2020, it’s commendable that the company still managed to produce an underwriting profit during the year.

Another thing that speaks to the appropriately-conservative approach of Markel’s leaders is the fact that the company has not been taking undue financial risks. This can be seen from Markel having kept its leverage ratio, which is the ratio of total assets to shareholders’ equity, low for a long period of time (more on this later).

The second thing we want to discuss is about Markel’s stock market investing activities. The company has a longstanding four-step approach for its stock market investments: (1) It looks for profitable businesses with “good returns on capital that don’t use too much leverage [in essence, leverage is debt]”; (2) it looks for “management teams with equal measures of talent and integrity”; (3) it looks for “companies with reinvestment opportunities and capital discipline”; and (4) it looks for these investments “at fair prices.” And Markel invests in each stock with the intention of holding it for the long run. The company’s way of investing resonates with us because it’s really about identifying great businesses and patiently holding their shares. Importantly, it’s a sensible way to invest and the company’s investment performance, led by Gayner, speaks to this.

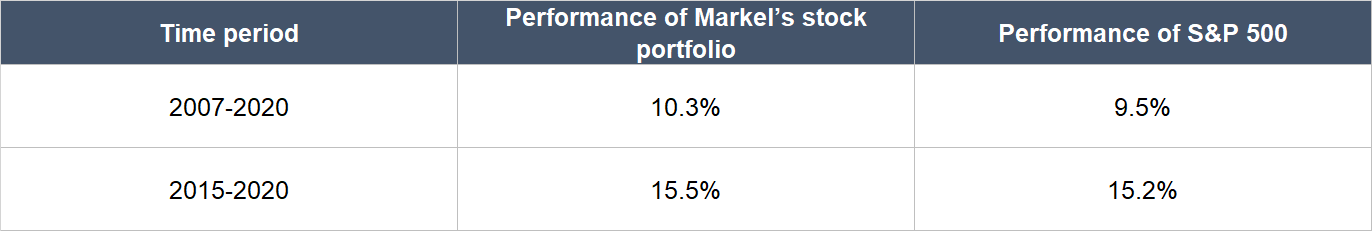

The table below illustrates the superior annualised returns of Markel’s portfolio of stocks versus that of the S&P 500 for two meaningful timeframes: 2007-2020 (2007 was chosen as the starting point here to observe how the company fared during the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis) and 2015-2020 (to see how the company fared over the last five years).

Source: Markel annual reports and Ycharts

The third thing we want to discuss deals with Markel Ventures, which was established in 2005. When selecting private companies to acquire for Markel Ventures, Markel uses the same four-step approach that it uses for stock market investing. Another important point about Markel Ventures is that Markel goes into every acquisition with the intention of being a long-term owner who cares deeply about the business and yet is willing to let it be run autonomously. Because of this, Markel’s reputation has grown steadily over the years and the company is increasingly becoming a preferred buyer for private business owners who are looking for a worthy home for their life’s work.

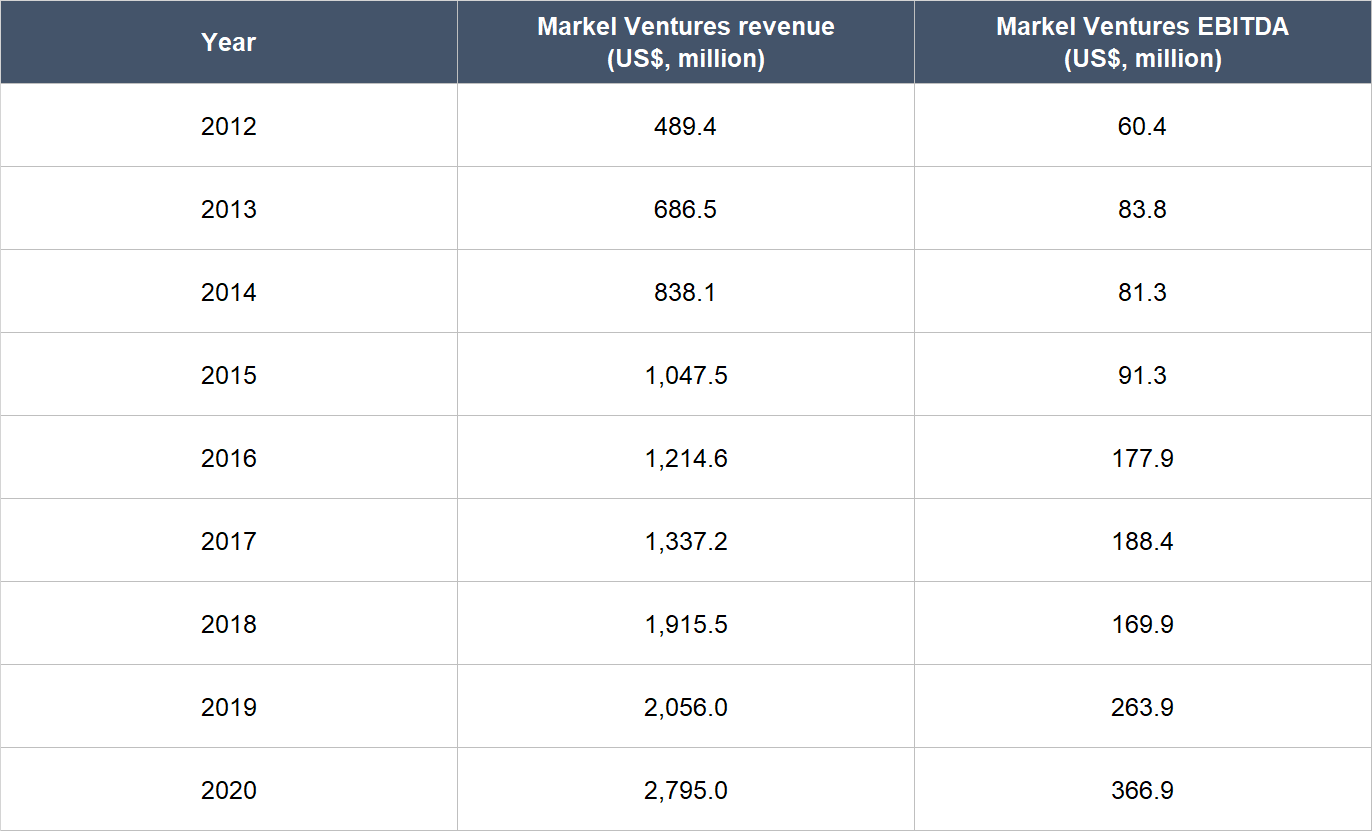

The results from Markel Ventures have been impressive. Over the past 15 years from 2005 to 2020, Markel has invested a total of US$2.7 billion for all the acquisitions that comprise Markel Ventures. The companies in Markel Ventures have so far produced dividends, and built up internal cash balances, of around US$1.2 billion. So, Markel has made a net investment of US$1.5 billion (US$2.7 billion minus US$1.2 billion) in a collection of companies that generated a solid US$367 million in EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) in 2020. For another perspective on Markel Ventures’ results, the table below shows the strong annual growth for its revenue (41.7%) and EBITDA (43.5%) from 2012 to 2020.

Source: Markel annual reports

The fourth thing we want to discuss is the unique mindset of Markel’s leadership team. Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett’s investment conglomerate, holds its annual general meeting in May each year in its hometown of Omaha, Nebraska (there was sadly no meeting in 2020 because of COVID-19). Although Markel is headquartered in Virginia, which is a long way from Omaha, its leaders have made the trek to Omaha every year since the early 1990s (except for 2020) to hold Markel’s own brunch event the day after Berkshire’s meeting. During Markel’s brunch, which is open to the public, its leaders, including Gayner, would answer any question from attendees. (Ser Jing attended Markel’s brunch in 2014 – feel free to ask him more about it!) The reason for Markel wanting to organise the brunches? We first need to go back in time to Markel’s founding.

Markel’s roots can be traced to 1930 when Sam Markel formed the Mutual Casualty Company to insure jitney buses. A few years later, Sam Markel’s four sons – Lewis, Irvin, Stanley, and Milton – joined the company and it became Markel. Over the years, the company grew and continued to have interests in insurance. By the 1960s and 1970s, the third-generation of the Markel family – Anthony Markel, Steven Markel, and Alan Kirshner (Anthony and Steven are cousins while Kirshner is a cousin-in-law) – have joined the company and begun to take on leadership roles. Markel was listed in 1986 and by then, the trio of Anthony, Steven, and Kirshner were all part of the company’s senior leadership team, with Kirshner being CEO, Anthony running operations, and Steven taking the lead on Markel’s finances and investments.

For a few years after its listing, market participants could not understand Markel’s idea – developed by Steven – of wanting to underwrite insurance policies profitably and make excellent long-term investments using the capital from the insurance business. By the early 1990s, Markel’s leadership had decided to make a trip to Omaha every year. This was because they knew of – thanks to Gayner – the fantastic long-term success of Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway in making great, patient investments with the profits from well-run insurance operations; Markel’s leaders figured that they could meet like-minded investors in Berkshire’s home.

To us, the story behind Markel’s annual pilgrimage to Omaha illustrates that the company’s management team has a unique mindset that they are willing to hold steadfastly to. And importantly, this unique mindset works – Markel’s share price has increased from US$22 at the start of 1990 to well over US$1,000 today. Often when people think about the word “innovation”, they will picture cutting-edge technology – Markel, as an insurance company, is not involved with such. But what Markel lacks in technological innovation, we think it makes up for with a unique mindset in the world of business. Even though Gayner and Whitt have no familial ties to the Markel family (as far as we know), we’re confident that Markel the company is in good hands. It helps too that Steven is currently Markel’s chairman, a role he inherited from Kirshner in May 2020. Kirshner, meanwhile, was Markel’s CEO from its listing in 1986 through to 2015, when Gayner and Whitt became Co-CEOs.

4. Revenue streams that are recurring in nature, either through contracts or customer-behaviour

Markel’s main revenue source is in insurance products. And insurance is a service that enterprises and individuals require on an ongoing basis, so there should be high levels of recurring business activity there for Markel.

5. A proven ability to grow

In our explanation of this criterion, we mentioned that we’re looking for “big jumps in revenue, net profit, and free cash flow over time.” But for Markel, our focus is on its book value per share. This is because Markel’s assets currently are mainly cash, bonds, and public-listed stocks. But if Markel Ventures grows over time (and it likely would), Markel’s book value per share will increasingly lose its relevance as a measure of the company’s intrinsic economic value. Markel Ventures’s companies are not represented on Markel’s balance sheet at their “market” values – instead they are represented at their historic costs. Because of this, Markel Ventures’ intrinsic economic value is not appropriately captured by the book value metric. For now though, Markel’s book value per share is still important.

The table below shows the company’s book value per share from 2007 to 2020, along with other important financial numbers. We chose 2007 as the starting point to observe how Markel fared during the 2008-2009 Great Financial Crisis.

Source: Markel annual reports

A few things to highlight from Markel’s historical financials:

- Earned premiums (the company’s insurance revenue) did not grow every year, but there’s still an unmistakable long-term upward trend. From 2015 to 2020, earned premiums compounded at 8.0% annually, which is similar to the growth rate of 7.8% per year for the 2007-2020 period.

- In a similar manner to earned premiums, Markel’s book value per share did not increase in every year for the period under study but had also increased meaningfully over time. For 2007-2020 and 2015-2020, Markel’s book value per share compounded at respectable annual rates of 9.7% and 9.6%, respectively. The book value per share did drop by 16% in 2008 (during the Great Financial Crisis), but then quickly recovered and grew in every year since, except 2018.

- Importantly, Markel did not achieve its growth by taking on undue financial risks. For the entire time frame we studied, Markel’s leverage ratio (total assets divided by shareholders’ equity) did not exceed 4.36.

- Dilution is not a problem at Markel. From 2007 to 2012, Markel’s weighted average diluted share count declined by 0.6% per year. There was a big jump in the share count in 2013 because Markel had issued 4.398 million new shares of itself to fund part of the US$3.3 billion acquisition of specialty insurance and reinsurance services provider Alterra in May of the year. From 2013 to 2020, Markel’s weighted average diluted share count had increased at a pedestrian pace of only 1.3% per year, and in fact, the share count had been declining in more recent years after peaking at 14.078 million in 2016.

- Markel managed to grow its book value per share by 10.4% in 2020. We think this is a commendable feat, given the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic during the year. Earlier, we mentioned that COVID-19 added six percentage points to Markel’s combined ratio in 2020 (remember, the lower the combined ratio, the better) and that 2020 was a year with a much higher number of weather-related catastrophes compared to the past. But that’s not all, the pandemic also caused wild fluctuations in the financial markets.

6. A high likelihood of generating a strong and growing stream of free cash flow in the future

Being predominantly a financial services company, the concept of free cash flow is not as important for Markel. So what we’re concerned with is the future growth in the company’s book value per share.

We think there’s a high likelihood that Markel will grow its book value per share in the years ahead at a similar rate as it had done in the past 10+ years. The company manages risk in its insurance business in a sensible manner, it has a good approach for stock market investing with a solid long-term track record of outperformance, and it has been making sensible acquisitions for Markel Ventures.

Valuation

We like to keep things simple in the valuation process. In Markel’s case, we think the price-to-book (P/B) ratio is a suitable gauge for the company’s value, for now. We explained earlier:

“But for Markel, our focus is on its book value per share. This is because Markel’s assets are mainly cash, bonds, and public-listed stocks at the moment. But if Markel Ventures grows over time (and it likely would), Markel’s book value per share will increasingly lose its relevance as a measure of the company’s intrinsic economic value. Markel Ventures’s companies are not represented on Markel’s balance sheet at their “market” values – instead they are represented at their historic costs. Because of this, Markel Ventures’ intrinsic economic value is not appropriately captured by the book value metric. For now though, Markel’s book value per share is still important.”

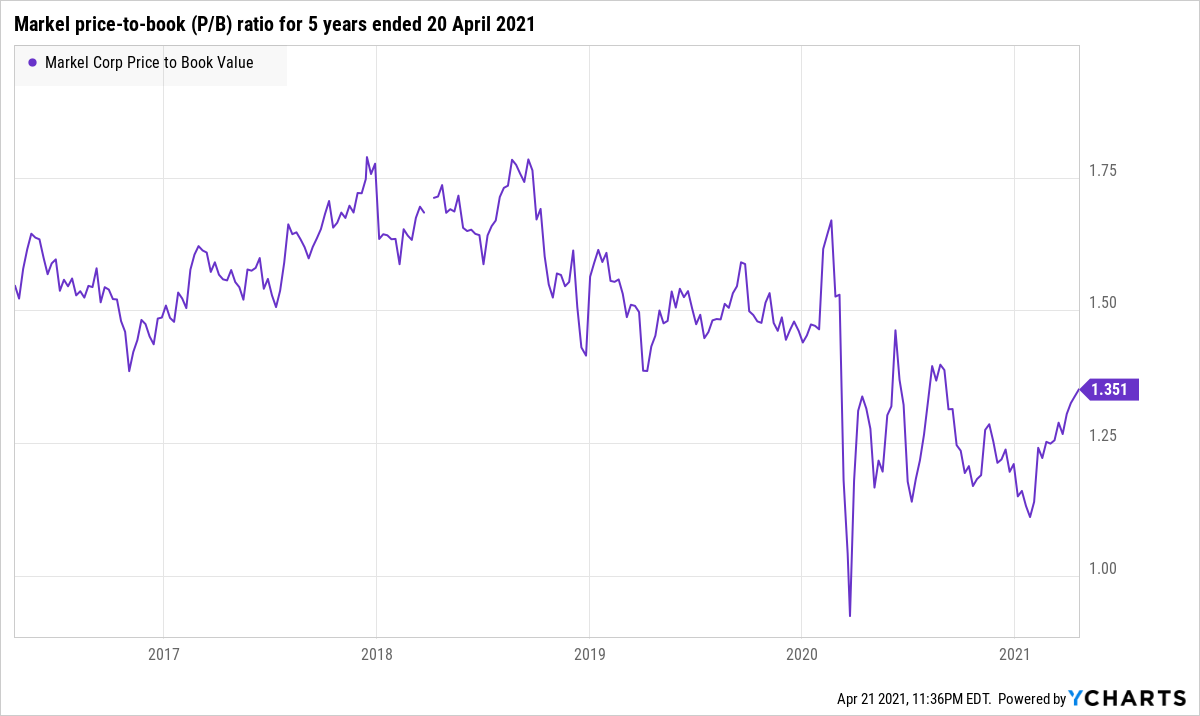

We completed our purchases of Markel shares with Compounder Fund’s initial capital in late July 2020. Our average purchase price was US$994 per Markel share. At our average price and on the day we completed our purchases, the company’s shares had a trailing P/B ratio of around 1.27. We think this is a reasonable valuation for a company that could likely compound its book value per share at a low-teens rate in the years ahead. Moreover, the P/B ratio of 1.27 is also not high in relation to history and so, there could be the possibility of our investment return with Markel being enhanced by an expansion in its valuation multiple. The chart below shows Markel’s P/B ratio over the five years ended 20 April 2021.

For perspective, Markel carried a P/B ratio of around 1.35 at the 20 April 2021 share price of US$1,197.

The risks involved

Markel’s future success relies heavily on Whitt’s ability to underwrite risk thoughtfully for the insurance business, and the investing and acquisition chops of Gayner. Should either or both of them lose their way, Markel’s growth could be stunted and in the worst-case scenario (where Markel underwrites lousy insurance policies that could result in massive claims and/or where Markel borrows significantly to buy shares or make poor acquisitions), even the survival of the company could be threatened.

Meanwhile, if either of Markel’s Co-CEOs leave the company for any reason, we’ll be watching the leadership transition. The good thing is that Gayner and Whitt are both relatively young at 59 and 57, respectively, so they should still have plenty of gas left in the tank to continue leading Markel in the years ahead. For perspective, Kirshner retired from his CEO role at Markel at the age of 80.

Summary and allocation commentary

In short, we think Markel can be described as a baby-Berkshire Hathaway in both form and substance. When it comes to form, Berkshire Hathaway, has three core economic engines: Its insurance-related businesses; a massive portfolio of fixed income investments and shares in public-listed companies; and a huge collection of privately-held businesses that span a wide variety of industries, from railroads to candies and energy utilities, and from industrial tools to ice cream and furniture retailing. As we had described earlier, Markel too has the same three economic engines. When it comes to substance, Buffett is famous for his integrity and long-term orientation in the world of business and investing. We think Markel’s leaders have the same traits too.

After weighing both the strengths and risks in Markel that we’ve identified, we initiated a 2.5% position – a medium-sized allocation – in the company with Compounder Fund’s initial capital. We appreciate Markel’s steady historical growth profile and the high chance it can continue with a similar growth path in the future. But our enthusiasm is tempered by our awareness that Markel’s historical growth rates are not the fastest.

And here’s an important disclaimer: None of the information or analysis presented is intended to form the basis for any offer or recommendation; they are merely our thoughts that we want to share. Of all other companies mentioned in this article, Compounder Fund only owns shares in Markel. Holdings are subject to change at any time.