What We’re Reading (Week Ending 27 March 2022) - 27 Mar 2022

Reading helps us learn about the world and it is a really important aspect of investing. The legendary Charlie Munger even goes so far as to say that “I don’t think you can get to be a really good investor over a broad range without doing a massive amount of reading.” We (the co-founders of Compounder Fund) read widely across a range of topics, including investing, business, technology, and the world in general. We want to regularly share the best articles we’ve come across recently. Here they are (for the week ending 27 March 2022):

1. RWH002: Investing Wisely In An Uncertain World w/ Howard Marks – William Green and Howard Marks

William Green (00:34:23):

Part of what’s curious to me though, is that I always had this image of you, having interviewed you several times, that I was sort of in the presence of a most superior machine, that you clearly had a lot of extra IQ points, but you were also very rational and analytical. But then what kind of started to mess with my head was that I started to realize, well actually you do have very strong intuition, and not only that, but you were a good artist as a young man, you’re a very good writer. There’s something kind of curious about your makeup, where there are these characteristics that seem kind of contradictory, or at least it’s very unusual to see them together in the same chemical experiment. Does that resonate at all that view of you?

Howard Marks (00:35:00):

I think so. I hope so. Because I’d hate to be able to be reduced to one dimension of some brain sitting in a tank some place turning out investment ideas. The investors that I respect are not all the same. Some write, some don’t, some draw, some don’t, some ski, some don’t. But they’re all bright. Buffet says, “If you have an IQ of 160, sell 30 points, you don’t need them.” But they’re all bright. I think they’re just about all unemotional, but you can be lots of other things. And in fact, I think you have to be able to, again, reach conclusions that are not analytically based, quantitatively based. You have to have some imagination.

Howard Marks (00:35:38):

If you go back and read the memos that I wrote, for example, during the Global Financial Crisis, October of ’08, which was the bottom for credit, it was a meltdown that was going on in the credit world that month. Or the one that I wrote two weeks earlier, it was, I guess Lehman went out bankrupt on September 15th of ’08, I think it was, so I put out a memo four days later titled, I think it was Now What? or something like that. I think it was Now What? You couldn’t figure out whether or not the world was going to continue to exist. You couldn’t prove that the financial institution world was not going to melt down. And a lot of people thought it would. And a lot of people were absolutely panicking to sell. And there was no experiment you could conduct, no calculation you could perform to prove that it wasn’t going to happen. It felt like a meltdown.

Howard Marks (00:36:26):

And we had Bear Sterns disappear and Merrill Lynch go into the hands of B of A and then Lehman bankrupt, Washington Mutual, Wachovia Bank. And everybody knew who was next, and who was after them. And it felt like falling dominoes. And so I wrote a memo, Now What? And I said, “What do we do now? Do we buy or don’t we?” And I said, “If we buy and the world melts down, it doesn’t matter. But if we don’t buy and the world doesn’t melt down, then we failed to do our job. We must buy.” Now that’s not scientific. It’s logical. I hope it’s logical. As you say, I think I’m logical. But it sure wasn’t quantitative or analytical or anything like that. It was an intuition.

William Green (00:37:08):

And there was a deep level of gut. Because I remember you coming back from a meeting with an investor who kept saying, “Well, what if it’s worse than that? What if it’s worse than that?” And you telling me that you rushed back to your office and you were like, “I’ve got to write about this.” Because sometimes it’s too bad to be true. So that’s actually again for somebody who I had viewed as a superior machine, actually, that’s a lot of EQ involved in seeing that and seeing, “Oh, people have melted down to this extent that they can’t see that things can get better.”

Howard Marks (00:37:35):

Well, I think that’s right. That was discussed in a memo. I think that was October the 12th of ’08. And that’s one of my favorites. It’s called the Limits to Negativism. But as an investor, one of our responsibilities is to be skeptical. And most people think that to be a skeptic, you have to blow the whistle when people are too optimistic. Somebody comes into your office and says, “I’ve managed money for 30 years. I’ve made 11% a year. I’ve never had a down month.” You have to say, “No, that’s too good to be true, Mr. Madoff.” But what I realized on that day in that meeting was that our job as a skeptic also includes blowing the whistle when it’s things that people are saying are too bad to be true, when there’s excessive pessimism. And that’s what that day was.

Howard Marks (00:38:15):

We had a levered loan fund. It was in danger of getting a margin call and melting down. So I went around to the investors, asking them all to put up more equity. And the one person that you mentioned said to me, “Well, what if this happens?” And I said, “Well, we’re still okay.” “Well, what if this happens, what if it’s worse than that?” Well, we’re still…” “What if it’s worse than that?” And I could not come up with a set of assumptions that satisfied her as to being negative enough. And she refused to participate in this re-equitization. So as you say, I ran back to my office, I wrote out the memo, and she was the only one who wouldn’t participate.

Howard Marks (00:38:51):

So I felt it was my duty to put up the money. I put up the money. It was one of the best investments I ever made. And I did it in part out of duty. You say EQ, one of the great things we can do, which has nothing… Well, it’s hopefully based on financial analysis, but when we have a sense for the excesses of emotion in the market, whether it be too optimistic or too pessimistic, if you can meld that with financial analysis to have a sense for what things are worth, see the differences from where they’re selling, understand the origin of the difference as coming in large part from emotional error, then you really have a great advantage.

William Green (00:39:30):

So when you look at today’s environment, as someone with 50 years of pattern recognition, with deep skepticism, but also with this renewed sense of humility about the fact that maybe some of your previous principles need to be updated because we’re living in a different world today. How do you look at this moment that we’re in now in this kind of impressionistic way that you do? Are you seeing evidence that it’s a time when investors need to be more defensive than usual, that too many people are taking too much risk? I’m just curious to see how you weigh the kind of optimism that’s baked into prices and behavior and deal structures and the like in the way that you do when you are looking to gauge a market?

Howard Marks (00:40:11):

Well, as I mentioned before, life gets harder when you have to give up on things never being different. And when you can’t live by a formula or a rule and the S&P 500 hit 3,300 on February 19th of ’20, and then it hit 2200 and change on March the 24th. So it was like 33 days later. And it was down a third. By June of ’20, it was back around 3,300, back to the all time high. And a lot of people said, “This is ridiculous because we’re still in a big mess. We still have a pandemic. The economy is still shut down. We just had the worst quarter in history for GDP. How can the market possibly be back intelligently to its pre COVID high?” So people started to blow the whistle and say, “Bubble, it’s a bubble.” And obviously now the stock market is a third higher than that. So it’s around 4,500.

Howard Marks (00:41:07):

So anybody who blew the whistle on bubble and went to the sidelines was at minimum too early. It’s now 20 months later. I would normally have been among the cautionary commentators. And maybe it was because of the conversations that were going on between me and Andrew. I couldn’t bring myself to do it because for two reasons. Number one, I think that a bubble is an irrational high. I think today’s prices are not irrational. They’re rational given the low level of interest rates. Interest rates have a profound effect on what something is worth in dollars and the lower the interest rate, the higher the value. So I think that today’s values are relatively appropriate given the level of interest rates. And the other thing is I believed and believe that we are looking at a period of healthy economic growth.

Howard Marks (00:41:55):

So we have rational prices, albeit low, and a good economic outlook. I don’t think that’s a formula for a collapse of the markets. And so I’ve given up on saying, “Buy, sell. In, out.” What I now say is, “If you know your normal risk posture, is today a time to be more aggressive or more defensive?” And I would say around your normal posture may be a little defensive, mainly because today’s prices are fair given the interest rates, but we all think that interest rates are going to rise somewhat, which means that assets will be worth less, somewhat, offset somewhat by the economic strength. But I don’t think it’s a time to take extreme action, timing wise, in either direction. I wouldn’t ramp up my aggressiveness, but I wouldn’t hide under the mattress.

William Green (00:42:40):

And you’ve lived through intense inflationary times before. Can you give those of us like me who haven’t been through this before, I’m 53, I didn’t experience it. Although one of my childhood memories was of my dad and my uncle getting smashed by the market in those days. How do sensible, prudent investors invest wisely during inflationary times? What are the tweaks you make to your portfolio just to sort of adjust the sales a little bit so that you’re likely to survive and prosper?

Howard Marks (00:43:08):

Well, first of all William, I get this question. Is this like the ’70s? And that was about with inflation. And number one, I believe that some aspect of today’s inflation is temporary because I think that there were supply chain interruptions, which took longer to work out than people expected or hoped. But it makes sense. A Toyota, I think has 30,000 parts. If one of them is unavailable, you get no cars for a while. So it makes sense. So I think that some of this and some of it is a bulge in demand, which came from too many people being given too much money in COVID relief in ’20 and early ’21. So an artificially high demand, artificially low supply, some of it will probably be temporary, depending on what happens with so-called inflationary expectations and whether they get baked in.

Howard Marks (00:43:58):

Number two, we have roughly 7% inflation now for the last eight, nine months. We had about twice that in the ’70s. Number three, nobody had an idea how to fix what was going on. We tried wind buttons, whip inflation now, we tried price controls, we had a pricing Czar. But they couldn’t figure out how to beat inflation. Now we know all you have to do is raise rates. Maybe it causes a recession, but you can do it. The other thing is that the private sector was heavily unionized in those days. It is not now. The union contracts had cost of living adjustments where if the cost of living goes up, you get a wage increase. But if you get a wage increase, it feeds through to the cost of the goods manufacturer. There’s more inflation and somebody else gets a wage increase. So it was circular and upwards spiraling. We don’t have COLAs anymore in our private sector.

Howard Marks (00:44:49):

So I don’t think we’re going to have inflation like we did then, or interest [inaudible 00:44:54] like we did then. I had a loan outstanding at three quarters over something called prime, if you remember prime. And I used to get a slip from the bank every time it changed, I have framed on my wall, the slip which says, “The rate on your loan is now 22 and three quarters.” I don’t think we’re going there, but we’ll have more inflation in the next five years than we did in the last five. There will be some unpleasant aspects to that. It’s important to remember that most of the world was trying to get to 2% inflation for the last decade or two, and they couldn’t do it. They couldn’t get inflation that high. Now it’s going to run hot for a little while.

2. Gaurav Kapadia – Everything Compounds – Patrick O’Shaughnessy and Gaurav Kapadia

[00:05:30] Patrick: Maybe you could describe the aspects of each of those dimensions where it ends up being the hardest, the types of situations in which it’s the hardest to be rigorous or the hardest to be kind, because like any company values that might sit on someone’s wall or in a poster or something, they’re hard to disagree with ever. They’re always aspirational and sound great and then are useless unless they’re, as you’ve described, constantly in practice. At some point, it’s hard to do that and it’s the whole point. So maybe pick for each one, I’d love to do both, an example, an anecdote, whatever, when it was really hard to stick to that standard.

[00:06:06] Gaurav: The first thing is people con sometimes confuse what rigor is and what kindness is. Kindness doesn’t mean just being unfailingly polite, or it can conflate the issue or being non-confrontational. One of the kindest things people do, they tell you the truth. Getting people in that mindset sometimes in the most difficult situation and most complicated interaction, the kindest thing to do is to say, as an example, tell someone that it’s unlikely they’re going to be promoted here or make a career here for the long run, and it hurts. I’ve had to do that many times. I’m crying, they’re crying, but in the end it ends up almost unfailingly I get a call a few years later saying, “You are totally right. That was the kind thing to do, and by the way, thank you for following up with me along the way to make sure I landed in the right place and mentor me, give me a reference,” whatever that is.

That’s a good example of things that are over the long-term kind, but feel cruel in the moment. Just being honest and transparent as a measure of kindness, rigor, I think people get rigor wrong in investing a lot, especially people who come through a specific analytical background. It’s not that you have to get your estimates or model perfect. That’s actually almost like the table stakes. Of course everyone we hire, interview can do that. What’s the rigor around it, which is how do you put pieces together? How do you take conclusions that are not obvious and stitch them together in a differentiated way? So that could mean chasing down some orthogonal competitor, going to a trade show. It could be looking at the end product. It could be just a different, more qualitative form of rigor. It doesn’t need to be quantitative necessarily, but it has to inform the mosaic to make you a great investor or a great colleague…

…[00:14:28] Patrick: What have you learned about the art of interacting with company management? So if you spend a lot of time doing that and you want to show that to the team, if I compared you when you were 28 or something to you today in an important management meeting, how would you be different today and how you conduct those versus then?

[00:14:46] Gaurav: Interestingly, the 28 versus today I don’t think is that different. I was very lucky in that I had a huge accelerator and a huge mentor very early in my career. So instead of going to investment banking or private equity out of college, I went to a consulting firm. I went to the Boston Consulting Group, and that it was a really interesting experience because when you’re 22, you have to interact with senior management teams immediately, and so that’s a real trial by fire. One of the things that I decided and I observed is very few investors, public or private view themselves as partners or advocates for the management team or companies. If you go to many meetings, they automatically start adversarial. They go, “How much shares are you going to buy back? Why do you miss your margins?” We never start by that. We lead with insight. We lead with work. We never go to a management meeting without tons of prep.

Almost always, we have a significant prep document that we often share with the companies so they know from the outset that we have the long-term interest of the company at heart and that we’re putting in the elbow grease to make sure that we understand what they’re trying to accomplish. That alone has been a huge differentiator. Can you imagine 90% of investor interactions are like, “Why didn’t you do this for me lately?” Hopefully, the ones with us are, “We see a lot of potential. We think the world’s not it. Help us understand it better. Can we help you understand how to communicate it better? What are we missing? How can we help? Do you need a customer introduction?” That just changes the tenor of the conversation. That started for me really early because I had this luxury of starting, I think, as a consultant. I worked for people my whole career who became successful very early in their own careers. I was lucky to be able to do that too, so there’s no hierarchy of seniority.

I would walk in, be prepped and hopefully, be able to lead the meeting to ask important questions, develop a really good relationship. It’s actually interesting, so these three executive partners that I mentioned and a bunch of the executives I still have relationships with. I met Carl when I was 24. I met Jan when I was 23 and I met Rob when I was 28. That relationship still carries through. One of the most gratifying things for me is that it’s not just me anymore. If you look across the whole organization, look outside this conference room, everyone here brings that kindness and rigor, the insight, the management interactions that I really want to pride our organization around, they do it independently. One of the really fun things I’ve been able to observe, because I have some of my colleagues here that I’ve known for 20 years, worked with five or 10 and seeing them grow and be huge and impactful leaders and partners is great. My favorite thing these days is when I talk to a CEO and they’re like, “Hey, Gaurav. Great to see you. I’m good. I’ll talk to one of your colleagues.” That’s a great way for me to measure-

[00:17:51] Patrick: Success.

[00:17:52] Gaurav: -our impact. Yeah. Yeah…

…[00:36:01] Patrick: I absolutely love the notion of trying to figure out what problem each company or leader of a company is dealing with at a given moment and having that be the wedge of the initial relationship. Is there a common pattern that you observe of those problems? What are the most common problems that you see people dealing with?

[00:36:17] Gaurav: One thing that investors don’t often realize is the stock price or the investor is often the last thing on the guy’s list of all the stuff he has to deal with. He has HR. He has an uprising at his company. He has unionization issues. So on the plethora of things they have to deal with, most likely, the thing that’s most important to you, it hasn’t even crossed their mind. And so being humble enough to know that is half the battle. You really try to understand. And by the way, you’ve got to do the work. It’s not like you just go and ask nice questions. Our largest public position is a company called Wabtec. It’s a combination of three mergers. There’s a big NOL. There’s a bunch of filings that you got to tie through. And once you do that, you kind of have an idea of what the issues are. How do I integrate this business? How do I go after these customers? What’s this transition to green energy going to do for the locomotive business? You focus on that and that opens up the aperture. Once you really hit what the CEO thinks or the core issues of the business, it really opens up your understanding of what the core issues of the business are. They’re not the same as what the rank and file industrial or sell side report would say.

[00:37:28] Patrick: Yeah, I love the idea that you are the bottom of the priority list of the person that you’re meeting. All too true, all the time. What are the then features of the business if you have a strike zone or an area of focus where you can potentially be that Jack Welch best-in-class or whatever? What defines that strike zone?

[00:37:46] Gaurav: Investing is complicated in two ways. You have to get the business right and then you got the valuation right. I think there’s people who are reasonably good at getting the business right. I think we’re hopefully better and we’re applying more analytical rigor and toolkits. Because even on the public side of the portfolio, we only have 10 to 12 positions at any time, so we could go really deep in them. And we hold them oftentimes for years and years and years, so we really have a long, longitudinal history. And now, we actually hold them from private to public, so we would have all that data too. Hopefully we’re better at that, and so there’s usually like an insight or a kernel that we see that the market doesn’t see. “Oh, the incremental margins are going to be so much higher.” “Actually, your market share in green locomotives is 20 points higher than your existing ones, and that’s a positive mix shift.” Or luxury’s going to move online. What’s the best way to capture that? So there’s some business insight. You got to marry though that business insight with asymmetry of share price in public or private. And so that’s really the art of investing. What you’re trying to find, generally speaking, is really good business that’s valued as a poor business or a mediocre business, that has the ability to compound through. That’s what I think we excel at, is this asymmetry with the business analysis. And so what that often manifests itself is you end up having optionality on multiple expansion and compounded capital growth in terms of free cash flow per share or something like that in the public or the private side…

3. The Chinese Tech Playbook for Winning – Part I – Lilian Li

Understanding whether a big market is winnable involves asking a few questions that may not seem straightforward. What is the end state of the market? What is the level of network effects in the market? Knowing the answer to the previous questions, when is the right time to get into the market?

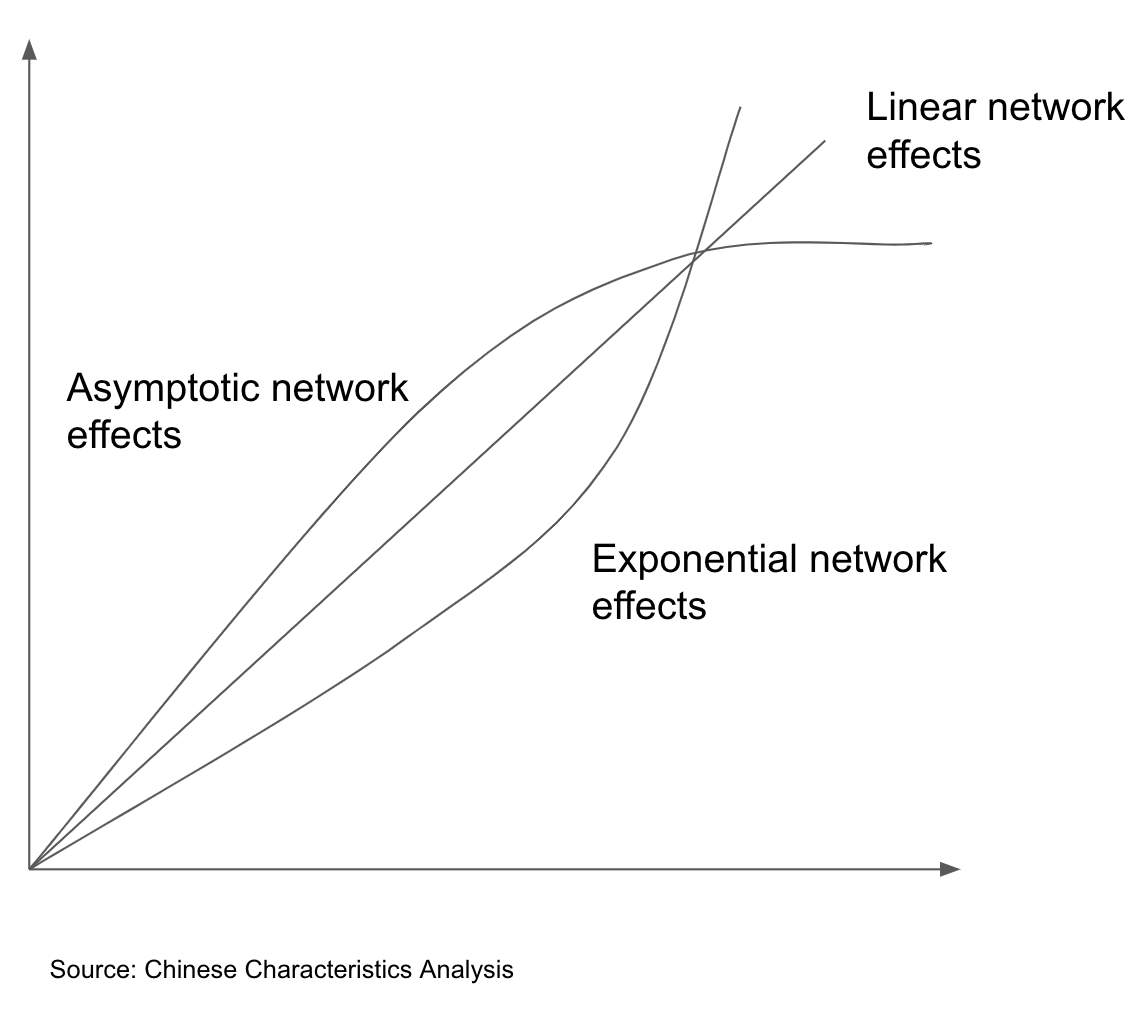

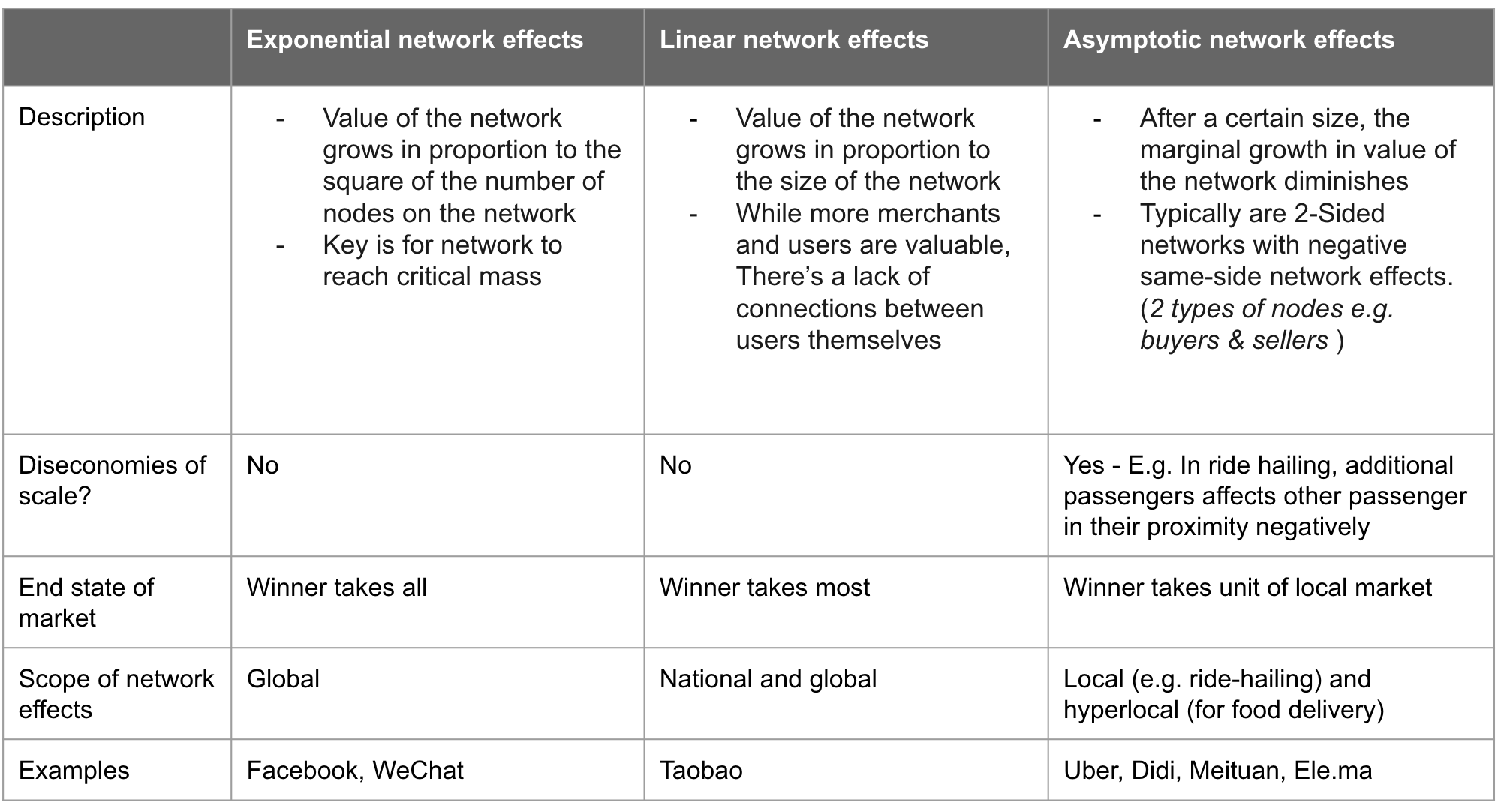

In asking about the end state of the market, inversion is used to understand how many big players the market can sustain. Is it one, three, seven or more? Here Wang has an exquisite framework where he draws a correlation between the level of network effects in the market to the degree the market exhibits winner-takes-all outcomes. Why are network effects important, we ask? As it’s an ever-present moat for most consumer companies, knowing its relative strength will deliver different entry, competition, and growth strategies.

Network effects are where the value or utility a user derives from a good or service depends on the number of users of compatible products. As size gets sufficiently big, advantages in user experience and cost base scale. Here’s a summary of the different types of network effects that can exist:

There is a deep linkage between the level of network effects in a system and how many top players it can sustain. Knowing there’s a graduation in network effects reveals the potential for new entrants into markets. While Taobao’s grip on e-commerce seemed all-encompassing during the 2010s, correctly knowing the limitations of its linear network effects can allow a founder or investor to bet on Pinduoduo’s emergence. Asymptotic network categories like grocery delivery or transportation platforms will always face new competition since effects are localised. This will lead to money burning protracted war without clear resolutions for years to come.

For markets with high network effects, such as search or social, getting to a segment early is all that matters. Once the race is on, it is hard to beat a market leader (even if the lead is slight at the onset) because of another effect in the digital age.

4. The Future is Vast: Longtermism’s perspective on humanity’s past, present, and future – Max Roser

Before we look ahead, let’s look back. How many came before us? How many humans have ever lived?

It is not possible to answer this question precisely, but demographers Toshiko Kaneda and Carl Haub have tackled the question using the historical knowledge that we do have.

There isn’t a particular moment in which humanity came into existence, as the transition from species to species is gradual. But if one wants to count all humans one has to make a decision about when the first humans lived. The two demographers used 200,000 years before today as this cutoff.1

The demographers estimate that in these 200,000 years about 109 billion people have lived and died.2

It is these 109 billion people we have to thank for the civilization that we live in. The languages we speak, the food we cook, the music we enjoy, the tools we use – what we know we learned from them. The houses we live in, the infrastructure we rely on, the grand achievements of architecture – much of what we see around us was built by them…

…How many people will be born in the future?

We don’t know.

But we know one thing: The future is immense, the universe will exist for trillions of years.

We can use this fact to get a sense of how many descendants we might have in that vast future ahead.

The number of future people depends on the size of the population at any point in time and how long each of them will live. But the most important factor will be how long humanity will exist.

Before we look at a range of very different potential futures, let’s start with a simple baseline.

We are mammals. One way to think about how long we might survive is to ask how long other mammals survive. It turns out that the lifespan of a typical mammalian species is about 1 million years.5 Let’s think about a future in which humanity exists for 1 million years: 200,000 years are already behind us, so there would be 800,000 years still ahead.

Let’s consider a scenario in which the population stabilizes at 11 billion people (based on the UN projections for the end of this century) and in which the average life length rises to 88 years.6

In such a future, there would be 100 trillion people alive over the next 800,000 years…

…But, of course, humanity is anything but “a typical mammalian species.”

One thing that sets us apart is that we now – and this is a recent development – have the power to destroy ourselves. Since the development of nuclear weapons, it is in our power to kill all of us who are alive and cause the end of human history.

But we are also different from all other animals in that we have the possibility to protect ourselves, even against the most extreme risks. The poor dinosaurs had no defense against the asteroid that wiped them out. We do. We already have effective and well-funded asteroid-monitoring systems and, in case it becomes necessary, we might be able to deploy technology that protects us from an incoming asteroid. The development of powerful technology gives us the chance to survive for much longer than a typical mammalian species.

Our planet might remain habitable for roughly a billion years.8 If we survive as long as the Earth stays habitable, and based on the scenario above, this would be a future in which 125 quadrillion children will be born. A quadrillion is a 1 followed by 15 zeros: 1,000,000,000,000,000.

A billion years is a thousand times longer than the million years depicted in this chart. Even very slow moving changes will entirely transform our planet over such a long stretch of time: a billion years is a timespan in which the world will go through several supercontinent cycles – the world’s continents will collide and drift apart repeatedly; new mountain ranges will form and then erode, the oceans we are familiar with will disappear and new ones open up.

But if we protect ourselves well and find homes beyond Earth, the future could be much larger still.

The sun will exist for another 5 billion years.9 If we stay alive for all this time, and based on the scenario above, this would be a future in which 625 quadrillion children will be born.

How can we imagine a number as large as 625 quadrillion? We can get back to our sand metaphor from the first chart.

We can imagine today’s world population as a patch of sand on a beach. It’s a tiny patch of sand that barely qualifies as a beach, just large enough for a single person to sit down. One square meter.

If the current world population were represented by a tiny beach of one square meter, then 625 quadrillion people would make up a beach that is 17 meters wide and 4600 kilometers long. A beach that stretches all across the USA, from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast.10

And humans could survive for even longer.

What this future might look like is hard to imagine. Just as it was hard to imagine, even quite recently, what today might look like. “This present moment used to be the unimaginable future,” as Stewart Brand put it.

5. A Fool and His Gold – Doomberg

When judging the potential economic value of a gold deposit, there are three critical questions: how much gold is in the ground, at what average concentration, and in what form? While all three are important, the last one is often the strongest determinant of gold mine economics. How the gold presents itself in a deposit dictates the means needed to isolate it in pure form, and those means can vary from easy to nearly impossible – at least financially.

On the easy end of the spectrum sit placer gold deposits that result from the weathering and disintegration of rock formations containing seams of gold, thus liberating the precious metals. Creeks and rivers then transport and concentrate the relatively pure gold over millennia, often depositing it at ancient river bends and in bedrock depressions. Placer gold can be isolated with water and gravity, using contraptions as simple as a pan or as sophisticated as a sluice box. Placer mining once dominated US gold production (it is still the form of mining profiled on the popular show Gold Rush) but the best and most accessible placer deposits have already been exhausted.

On the more difficult end of the spectrum sit lode deposits, where the gold is still trapped inside rocks and veins, surrounded by minerals and other impurities. Here, extracting and concentrating the gold is more challenging and usually involves crushing the rock in a mill, leaching the ore with a cyanide solution, isolating the high-value metals, and forming them into doré bars which are sent to refiners for final processing. No two ores are alike and the exact details of the process flow required vary from mine to mine.

The above process works well enough for oxide ores where the gold is trapped in silica minerals like quartz. It’s a different story for the class of deposits known as sulfide ores, where the gold is surrounded by sulfides of iron. Sulfide ores are so difficult to mine they are often categorized as refractory deposits, and the gold industry has spent decades trying to develop cost-effective methods to free this gold from its stubborn prison. Here’s how a recent study from McKinsey frames the issue (emphasis added throughout):

“Gold miners are facing a reserves crisis, and what is left in the ground is becoming more and more challenging to process. Refractory gold reserves, which require more sophisticated treatment methods in order to achieve oxide-ore recovery rates, correspond to 24 percent of current gold reserves and 22 percent of gold resources worldwide (Exhibit 1). Despite offering a higher grade, these ores can only be processed using specific pretreatment methods such as ultrafine grinding, bio oxidation, roasting, or pressure oxidation (POX).”

Knowing this, imagine our shock when we woke up on Tuesday, March 15, to the news that AMC Entertainment Holdings (AMC) had invested in a gold mine!…

…Hycroft’s only mine has been in and out of operation for several decades, but most of the easy oxide ore was mined throughout the 1980s and 90s. While meaningful amounts of gold remain in the ground, it is predominately difficult sulfide ore, and the concentration of gold is quite low. In other words, the Hycroft Mine is a low-grade refractory deposit from which it is nearly impossible to extract gold in a way that makes money. Not that others haven’t tried.

In 2014, the mine was owned by Allied Nevada Gold Corporation, which launched an ambitious $1.4 billion plan to revitalize the mine and crack the sulfide ore challenge. By March of 2015, the company filed for bankruptcy protection:

“U.S.-based gold miner Allied Nevada Gold Corp filed for bankruptcy protection on Tuesday, buckling under a heavy debt load amid weaker metal prices. Allied Nevada, which owns the Hycroft open pit gold and silver mine in Nevada, said in a statement it was filing to restructure its debt, which stood at $543 million at the end of September.”

Allied Nevada emerged from bankruptcy as a privately-held company in October of the same year and was renamed Hycroft Mining Corporation. The company continued to wrestle with the difficulty of mining its sulfide ore, with minimal success. In January of 2020, during the early stages of the Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) boom, Hycroft agreed to be acquired by Mudrick Capital Acquisition Corporation and became a publicly-traded company once again on June 1, 2020. To address the predicament of economically mining a low-grade refractory deposit – a requirement of survival – the slide deck promoting the deal claims a proprietary, patent-pending breakthrough technology for processing sulfide ores:…

…In every quarter since the SPAC transaction, Hycroft reported operating losses, negative free cash flow, and continually managed down expectations about the viability of their “Novel Process” to economically extract gold from sulfide ores. Then, in mid-November, the company reported its Q3 2021 results with a press release that was a classic “turn out the lights” moment. The chair of the board resigned. The chief operating officer – who had just been hired in January of 2021 – resigned. Most importantly, the company came clean on the failure of the sulfide ore technology, fired half its workforce, and ceased its run-of-mine operations:

“The Company has previously discussed its strategy for developing an economic sulfide process for Hycroft. Based on the Company’s findings to date, including the analysis completed by an independent third-party research laboratory and the independent reviews by two metallurgical consultants, the Company does not believe the novel two-stage sulfide heap oxidation and leach process (“Novel Process”), as currently designed in the 2019 Technical Report dated July 31, 2019 (“2019 Technical Report”), is economic at current metal prices or those metal prices used in the 2019 Technical Report. Subject to the challenges discussed below, the Company will complete test work that is currently underway and may advance its understanding of the Novel Process in the future.”

A technology miracle was needed to make the Hycroft Mine viable, and none was forthcoming. Virtually every major gold miner in the world has been working on finding economically viable ways to extract gold from refractory deposits, and to think that a decades-old mining operation that spends virtually nothing on research and development and relies on outside consultants and third-party research laboratories for their technology needs would produce a Holy Grail outcome is the height of lunacy. The stock traded below $0.30 a share, and bankruptcy seemed inevitable.

6. When the Optimists are Too Pessimistic – Nick Maggiulli

What happened from March 2020 to August 2020 reminds me of an incredible piece Drew Dickson wrote on Amazon that had an intriguing thought experiment.

Imagine it’s 2007 and a bunch of research analysts are debating what Amazon’s revenues will be like in 2020. One group of these analysts (let’s call them the “value” group) believes that Amazon will have $27 billion in revenue in 2020. But another group (let’s call them the “growth” group) thinks Amazon will have $37 billion in revenue by this time.

The two groups disagree on almost everything. They have different assumptions about expected GDP growth rates, Amazon’s margins, and what Amazon’s earnings will look like in 2020. Yet, despite their differences, both groups turned out to be astronomically wrong. Because Amazon’s revenues weren’t $27 billion or $37 billion in 2020, they were $386 billion!

This demonstrates why Amazon has been such an exceptional stock, but it’s also demonstrates how upside surprises are often overlooked by investors.

Why is this true? Because people hate losses much more than they love gains (*prospect theory has entered the chat*). As a result, they spend far more time thinking about downside surprises (market crashes) than upside surprises (extraordinary growth). Nevertheless, upside surprises happen more often than people realize.

7. 10 Lessons from Great Businesses – Mario Gabriele

The Collisons’ business shines by converting complexity to simplicity. Stripe absorbs the scuff and tangle of payment infrastructure so that it can radiate clean technical primitives. It is fitting that the company’s founders also apply this talent in other domains. Perhaps most usefully, it plays a vital role in Stripe’s culture.

The best example of this is the firm’s approach to recruiting. Attracting exceptional people is a startup’s most important task outside of finding product-market fit. Much has been written on the tricks and tactics to secure top talent. What interview process produces optimal results? What perks are most persuasive?

All of these things matter. But, we can simplify. More than any particular stratagem or scheme, the most effective way to hire extraordinary people is to be so persistent it hurts. From The Generalist’s piece on Stripe:

Patrick notes that “the biggest thing we did differently…is just being ok to take a really long time to hire people.” It took the company six months to hire its first two employees. Describing their “painfully persistent” process of recruiting in his conversation with Lilly, Patrick noted that he could think of five employees that Stripe had taken three or more years to recruit.

Like Stripe itself, this maneuver is the sort of thing that sounds simple – like accepting payments online – but is deceptively tricky. Persistence and pestering are twins with scarcely a mark to distinguish them. The difference is articulation, tone. If you can find the right words, the right message, you can persist – if you fail, you pester. Attempting to thread this needle involves some jeopardy of one’s emotions (it does not feel nice to badger) and reputation. But how often do we stop right before we succeed? How often do we stop one ask too soon?

Though The Generalist does not have the prolific hiring requirements of a high-growth startup, I have found the Collisons’ framing broadly applicable. When you see an exceptional opportunity or happen upon an extraordinary potential partner, find the words. Find a way to be absurdly, painfully persistent.

Disclaimer: None of the information or analysis presented is intended to form the basis for any offer or recommendation. Of all the companies mentioned, we currently have a vested interest in Amazon, Meituan, Meta Platforms (parent of Facebook), and Tencent (parent of WeChat). Holdings are subject to change at any time.