What We’re Reading (Week Ending 22 May 2022) - 22 May 2022

Reading helps us learn about the world and it is a really important aspect of investing. The legendary Charlie Munger even goes so far as to say that “I don’t think you can get to be a really good investor over a broad range without doing a massive amount of reading.” We (the co-founders of Compounder Fund) read widely across a range of topics, including investing, business, technology, and the world in general. We want to regularly share the best articles we’ve come across recently. Here they are (for the week ending 22 May 2022):

1. Flexport: How to Move the World – Mario Gabriele

The name “freight forwarder” is strange. It’s the kind of term whose meaning seems literally evident but is blurred by a sort of tedium-cloud. It is the cousin of descriptors like “insurance agent” and “data analyst.”

A freight forwarder is a tour guide for objects. Or, at least, that is how I have come to think of it after having it explained to me (and re-explaining it to myself after I have forgotten) by a series of patient people over the years. For, say, a shipment of pillows to make its way from Taiwan to France, it must move between ships, planes, trains, and trucks. As many as twenty different companies may be involved in a single shipment, each handling one stint of the multi-modal journey. Critically, each party is incentivized to care narrowly about their leg rather than the entire trip.

The freight forwarder sees this salmagundi of boats and warehouses and flight maps and says, Don’t worry, I’ll take care of it. With the savvy of a good tour guide, it helps the customer navigate the mess, keeping the itinerary, forewarning chancy routes, bum ports (the “bad neighborhood” of logistics), and charting an optimal path. They are the concierge of conveyance, consiglieri of transit.

As it turns out, this is a big business. The global freight forwarding market is pegged at around $182 billion with projections to reach $221 billion by 2025. That amounts to a modest compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of a tick below 5%.

This is also an extremely fragmented space. As of 2020, DHL Global Express led the market with 6% of annual revenue. Kuehne+Nagel and DSV+GIL followed with 4% each, succeeded by DB Schlenker and Nippon Express at 3%. Fully 60% of the market is composed of “others” – smaller providers that hold less than 2%, and perhaps not more than a few deciles…

…Chen’s primary mission is to guide Flexport into a phase of automation that lays the groundwork for its global trade platform ambitions. When I asked Chen which initiatives best showcased the company’s burgeoning abilities on this front, he shared two examples.

First, Flexport is devoting serious resources to digitizing global trade documents. Ingesting data from different languages and formats is the first step in building a library of “facts” around a shipment. Instead of “optical character recognition,” or OCR, Flexport relies on machine learning models developed with Scale AI. Whereas Flexport used to transform accurate data from documentation in two days or less, the recent partnership has helped the company do it in minutes while maintaining 95% accuracy. Chen noted that the reason accuracy sat short of 100% was not a technical issue but a result of human error at the outset.

Second, Flexport is developing models to predict when a shipment will arrive to be unloaded at a given port. Getting seemingly simple things right can have meaningful downstream effects. Knowing when a ship is ready to be unloaded influences when a truck should arrive, for example. This, in turn, impacts how a warehouse might organize its space. Just as snafus in one part of the supply chain can lead to misery elsewhere, improvements can create secondary and tertiary efficiencies. According to Chen, Flexport is well-positioned to produce reliable models to this end thanks to its existing freight forwarding business, saying, “We believe we probably have the highest accuracy.”

2. #028 – PM Lessons by Meituan Co-Founder – Pt 22: Demand and Supply – Tao

Understanding demand and supply is hard. Although you can only be in one of two situations: 1. demand outstrips supply or 2. supply outstrips demand, it’s hard to know at any point in time, which situation you’re in.

In our day-to-day work, these are the common problems that we’d encounter that have to do with demand and supply:

- The team doesn’t proactively determine the situation of demand and supply. As a result, the operation lacks focus, and the approach is basically “throw it against the wall and see what sticks“.

- The team knows that demand and supply each affects the other, but can’t make a clear judgment about which one is more important.

- The judgment about demand and supply is correct, but the operation is not guided by the prevailing demand and supply conditions.

If any of the above three situations occurs, then the team would usually work in the opposite direction of the demand-supply condition. In fact, they may even have a strong incentive to get it wrong!

For example, if a company is in a situation where supply outstrips demand, it should be doing more work on the demand side. In reality though, more often than not, it’s still pushing hard on the supply side.

Why?

If supply outstrips demand, then the demand is very important. The demand side buyers know they’re important, and they’d be very hard to entertain. In comparison, the supply side sellers would be a breeze to spend time with because they’re the ones who are in a hurry and have something to ask for. As such, the team would have a strong incentive to continue working on the supply side and pretend the harder-to-deal-with side is less important. This was a frequent occurrence in Meituan…

…Here’s another example from the retail industry to demonstrate how frequently people get the demand and supply relationship wrong.

I asked the bosses of convenience store and supermarket chains, “In the retail industry, which one is more important, demand or supply?“

Without exception, all of them answered that supply is more important.

It doesn’t gel with my business common sense – with the industrialized manufacturing that we have today, most goods should have more supply than there is demand.

Therefore, the next question to figure out is – is this how they think, or is this how they act?

So I asked them another question, “At your company, what work do you absolutely have to do yourself?“

They all answered, “Choosing the location“. One of them even said he personally chose the location for close to a thousand stores they have all over the country.

For retail, location is the aggregation of demand. They say supply is more important, but their actions are pretty revealing.

3. Arena Show Part I: Idea Dinner + YC Continuity – Benjamin Gilbert, David Rosenthal, Packy McCormick, Mario Gabriele, Shu Nyatta, and Anu Hariharan

Anu: It is so true. I also think it’s really hard to understand and appreciate an organization like YC from the outside. You really deeply understand YC in only two ways, if you’re a YC founder and if you work within YC.

When I was at Andreessen Horowitz, I actually did not understand the depth and the cultural nuance with which YC was built. It’s really hard to grasp that.

David: Can we talk about that for a minute? I put this in the notes. My current mental model of YC is like a university, a top Ivy League University. It’s very hard to get into. You take classes every year or every six months. There’s an endowment attached to it, which is Continuity now.

Ben: Wait, David. What do you mean by endowment? Are you saying that all of the proceeds from YC exits go into a big pool of capital that then funds Continuity? Is that what you’re suggesting by endowment?

David: No, but I’m curious if that’s the case. I meant more just like, it’s really weird that a large part of the private capital markets and the venture capital markets in America, those dollars come from educational institutions, mostly private educational institutions. That’s just very bizarre. Anyway, that’s kind of what I meant. Is that a good mental model of YC? What is it like?

Anu: Yes. In fact, we say that. We say YC is university for startups. Think of the accelerator as the undergraduate program and Continuity is the graduate school.

We are modeled after university in the sense of we have applications you don’t need to know anyone to apply to YC. Second, we were the first to do mass production of investments in a batch of startups. No one had ever done that. Everyone usually does, I met a set of companies, we have a Monday partner meeting, and you pick one or two.

YC from day one was a batch. They always received investments together. That, I think, goes to the insight that the founders of YC had at the time, which was entrepreneurship is lonely. Being in a group is how you motivate each other to learn from each other. And that’s your peer group.

Fundamentally, it came from the approach of a university. Continuity is graduate school. As I talked about, Series A is just one of the programs we run. We have two others, Post-A and Growth. Post-A focuses on two months within you raise the Series A. That’s a six-week program. We rebatch you, so now you have a new set of peers.

Our scale founders come teach how to form a recruiting team, how to hire engineers, because your job changes as a CEO. No one is writing a book about how your job changes and how to learn. Remember, the median age of a YC founder is 27, which means they have probably managed the sum total of three people in their life before these founders.

David: They really are like undergrads.

Anu: Yeah. You cannot expect them to know. How are you going to provide resources so that they can learn from others and they do as few mistakes as possible and as quickly as possible? Because when you’re scaling, you just go on a rocket ship, but the amount you demand out of these founders is a lot. The bar you’re setting is really high.

In our community, that’s why Brian Chesky comes to speak every batch. He’s the opening speaker of every batch. Right now, for all these programs that we run, the group program is how to scale as a CEO. That’s literally the program. It’s an eight-week session. It talks about hiring execs, performance, management, culture, and so on.

We have scaled founders and scaled exec. Tony Xu comes for that. His execs, the CFO of DoorDash, the head of engineering of DoorDash, come for the respective session. It’s really good to see the entire community working to transfer their learnings to the next batch of companies…

…Anu: At YC, I would say, if I had to pick one thing YC is really good at across both early and Continuity is we go by based on founders. I know it sounds cliche, but I think we also have an incredible advantage in assessing what makes a founder a really good founder.

We have incredible amounts of data, pattern recognition, and learning that we have honed it to a point that we know how to spot them. You all have heard of the famous 10-minute YC interview and everyone asks, how do you know in 10 minutes? The fact is we probably know in the first two minutes.

We actually don’t need the full 10 minutes. But sometimes, one or two people will surprise us with the end of the interview. I think the three things that can articulate what it is on the founder we look for.

One is the continuity stitch. Often in the growth stage, people pay attention to the founder, but they don’t. If you’re at a venture fund or a growth fund, you probably hang out with the founder for a week or two weeks before investment, some a total of three hours. By the time Continuity invest, I probably know them for years, or months, and I’ve had those interactions.

Ben: You’re saying that you’re paying attention more to the qualitative founder properties—even at the growth stage—than you are to their specific growth rate, or what their margins look like, or anything like that?

Anu: Yes, but if the three qualities hold, the metrics will show. I can either look at metrics, but sometimes metrics don’t tell you how good the internal sausage making is. Many people can package the metrics in a fundraise deck. It’s very well done. We teach you to do it.

We’re really experts at it. Therefore, we know it’s going to look great. We also teach them what points to emphasize on. We actually do practice runs. In Demo Day, we actually even write the script sometimes if they don’t understand what it is.

David: That’s a how-can-I-help moment.

Anu: Yeah. What we look for is, how fast does the founder move? What is how fast do they move mean? How fast do they ship? How fast do they iterate? Is it single biggest indicator and correlation to how successful they’re going to be and how soon?

You won’t be right about members’ many decisions early on, but at least, are you learning from them fast? And are you making changes? That’s one we measure. Second of the growth stage is how well are you hiring. If you’re sloppy in hiring, it always hits a wall.

One of the things we look for is how well are they hiring engineers, how well are they hiring execs. Will they be able to convince an incredible exec to come join them? That’s second. Third is clarity of thought. Clarity of thought in the growth stage for us is, can they write out two pages what makes this a $5 billion or a $10 billion company really well?

If you’re doing those three things, you’re going to be on top of your metrics, your product-market fit, your attention. There will be rough edges. I think because of YC, we’ve had the benefit of watching everyone from day one.

We know how Tony scaled. We know deeply well how Josh had Gusto scale. We know a lot of those founders. We then know, okay, these were rough edges, these are okay. These other founders had and this is how you and I know.

David: We’ve told a lot of these stories on Acquired. If you’re a growth investor looking at these companies new, you’re like, I know this is all going great, but you know those companies don’t always all go great. Tony had some serious near death moments. Airbnb was not up into the right journey the whole time.

Ben: If I had to summarize, I know we’re interviewing you. Not me here, but it seems like you invest based on the inputs rather than the outputs or maybe the leading indicators rather than the trailing indicators, where if somebody’s operating with those three principles, the business probably won’t consistently produce the results that someone would like to look for in the growth stage investment. They have a much higher probability at any given time of producing high quality results because those are the inputs that matter.

Anu: Absolutely. That’s why we feel strongly that inputs can be influenced. If you’re learning best practices and those are your inputs, then you can actually influence company building. When Tony comes and teaches our Growth Program and says these were my darkest moments, these are my mistakes I made, and I sure hope you don’t make the same mistakes, but these are two things I did really well, that’s incredibly valuable. That color is very hard to get outside of YC.

4. 2022 SaaS Crash – Alex Clayton

The rapid decline in value of public SaaS companies over the past 6 months has undoubtedly already had a huge impact on private market valuations. That downward trajectory may continue even if the public markets stay flat at today’s levels. If public market returns cannot fuel venture capital fundraising from their limited partners, the flywheel will slow down. Investors will have fewer dollars to invest, companies will have less cash to hire and invest in growth, and outcomes are likely to be much smaller than previously thought. This reset has been swift and will soon be painful for many businesses that are burning too much money and/or those that will have to slow top-line growth. Moreover, there will be wide-ranging implications for employees and investors not only in the SaaS community but for all private technology markets.

And while much of the focus has been on the decline in valuations, there is another huge factor that can’t be overlooked – how could a recession or broader economic slowdown affect your financial profile? This could have an even bigger impact on valuations if the fundamentals of businesses change for the worse. While a large part of the sell-off has consisted of a move away from riskier asset classes in sectors such as high-growth SaaS to cash and value stocks, recent earnings results have been strong and business fundamentals have not changed broadly. But what if you traded at 50x forward revenue and are now trading at 10x, and your associated forward revenue also dips by 30-40-50% from your prior plan? The outcome is not pretty and one we have not yet seen, but could soon if the 2008-2009 Great Recession is any indicator.

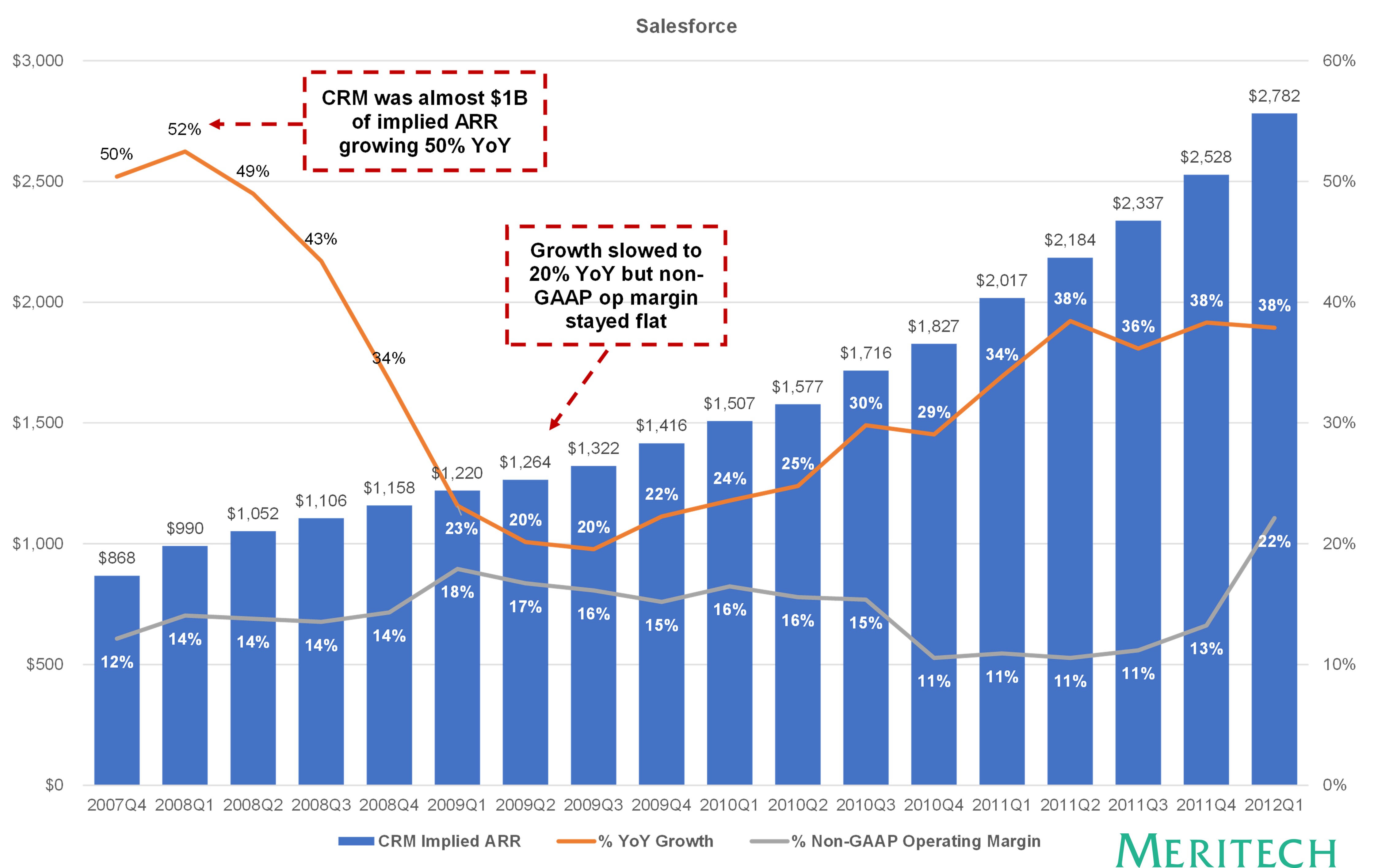

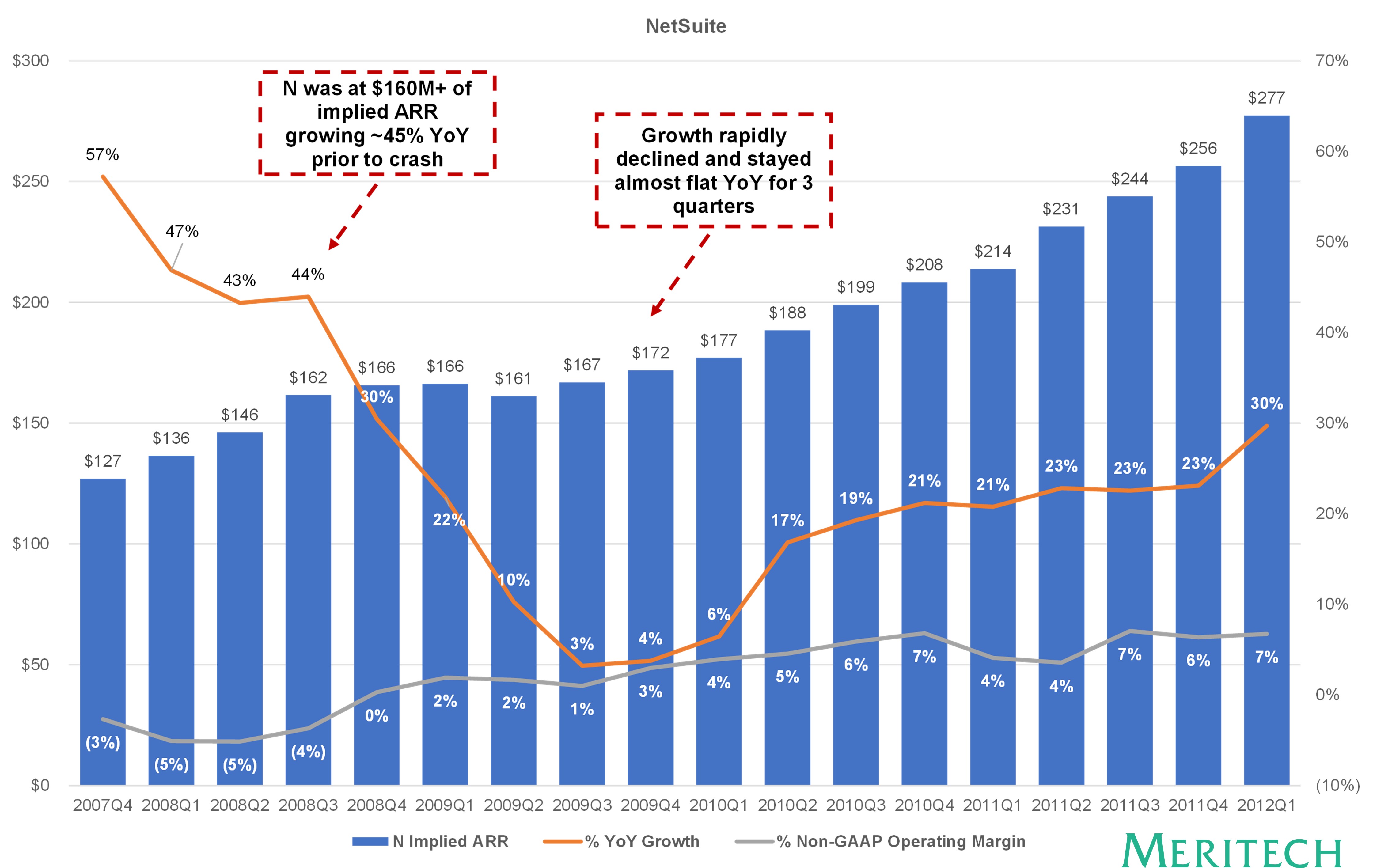

The following charts look at Salesforce* and NetSuite*, two publicly traded SaaS companies during the 2008 Great Recession, and what happened to their respective value and financial profiles. Unfortunately, while this is a small sample size, these are the best precedents as almost all other SaaS companies went public after the Great Recession…

…Salesforce was almost a $1B implied ARR (annualized revenue run-rate) business growing over 50% year-over-year at the start of 2008. During the Great Recession, revenue growth slowed to 20%. Non-GAAP operating margins did hold fairly steady, though…

…NetSuite was over $160M in implied ARR growing ~45% YoY at the end of 2008 before slowing dramatically. The company did not grow for 3 quarters in a row before accelerating back to growth. Similar to Salesforce, they also held non-GAAP operating margins constant but slowed investment significantly. It would be hard to imagine a ~$150M ARR business today that’s growing fast grinding to a halt, but this happened for NetSuite. The company also sold to SMBs and the mid-market, a segment that was hit particularly hard during the Great Recession.

5. TIP447: How To Build A Human Bias Defense System w/ Gary Mishuris – Trey Lockerbie and Gary Mishuris

Trey Lockerbie (16:25):

Fascinating stuff. So I want to move on to the next one, which is base-rate neglect. So there’s this phrase that’s come up, I don’t know, maybe over the last decade, maybe longer, but it’s don’t fight the Fed. And we’ve seen a lot of help from the Fed when markets have declined in the past and we’ve seen the Fed reverse course on say, raising interest rates quickly due to recessions and other liquidation problems around the world. So from this, we may have misconceived notions on how either the Fed will react to markets if they continue to decline from here, for example, which would thus enact this base-rate neglect human bias. So walk us through what the base-rate neglect bias is and how we might be able to avoid it.

Gary Mishuris (17:05):

Yeah. So I think it’s fascinating that… And I think sometimes people talk about inside view versus outside view. So base-rate neglect refers to ignoring the experience of others in similar situations and just making an assumption based on what we think we can do in this situation. So let’s say a very simplistic example of someone flips coins 1,000 times, they get 50% heads, 50% tails for a fair coin. And somehow we convince ourself that we can take a fair coin and flip tails 70% of the time. And that sounds ridiculous when they phrase it that way, but sometimes essentially that’s what is happening.

Gary Mishuris (17:42):

So, for example, if you study great investment records, which I’m sure you do, you realize that there’s a certain range of access returns over decades that the best investors have been capable of. And if you take Warren Buffett out of the picture and if you take people who use leverage out of the picture, unlevered returns, there’s almost nobody over decades has exceeded 5% per year access returns with no leverage and so forth. Obviously, Buffett has done close to 10, but I don’t think there’s going to be another Buffett necessarily.

Gary Mishuris (18:11):

So when someone shows up and they think they can do 10, what they’re doing is they’re exhibiting example of base-rate neglect. They’re looking at their own strategy and they’re saying, I have these clever mental models, I have this process, I have this special sauce. So they start to believe their own marketing deck a little bit too much, and they forget that the people who tried and failed to achieve the 10% for years, as an example, have also had their special sauce and their analyst teams and this and that, and yet they were only able to do a certain…

Gary Mishuris (18:42):

Think about someone like John Neff who record is public or who had three decades of returns. He beat the market by 3% per year in arguably less efficient markets than they are today. So when someone shows up and says, “Oh, I’m going to beat the market by 10%,” that’s a little bit crazy, it’s a little bit arrogant. And again, I think we’re all overconfident, but come back to the Fed. So look at the last 10 years, we had almost a perfect confluence of events. We had interest rates coming down. We had unrivaled Fed manipulation of markets far beyond just the short term end of the curve. We had maybe as a result there or maybe as a coincidence, huge amount of speculation, both by retail investors and by a number of “institutional” investors, institutional in quotes, not naming any names, don’t ask. And you basically had over the last five years, you had 25% CAGR for large growth stocks or all cap growth stocks.

Gary Mishuris (19:33):

So if you are investing in the universe, it’s pretty easy to start believing your own BS and start saying, well, gee, yeah, no, I can crush the… I can do 20, 25% per year, but like really? Let’s zoom out over the long term US equities return inflation plus six to seven, depending on the time period. So if you think you can do 20% plus, you think you’re going to beat the market by double digit percent per year. And I know everyone thinks they’re very special, but that’s just a perfect example of the inside view. The inside view is all these specific details for why the past experience of others doesn’t matter. And the base rate is the past experience of others in a similar situation. And I think the best thing you can do is zoom out and say, “Well, whatever I think about my own capabilities, let me put a heavy weight on the experience of others and a small weight on why I think I’m going to do so much better.” And that’s probably the best you can do.

Trey Lockerbie (20:25):

That’s interesting, because I was wondering the distinction here between say the base-rate neglect effect versus say the recency bias effect, because what I was describing, I don’t know, it could maybe fall into both categories depending on how you look at it. So recency bias is when you’re essentially taking events from the past and extrapolating them into the future. So how exactly is that different or what are maybe some other distinctions between that and the base-rate neglect effect?

Gary Mishuris (20:49):

So I think a recency bias is almost a special case of base-rate neglect. So what are some examples of recency bias? Let’s say you have a company over the last couple of years, it’s been growing 30% per year and you assume it’s going to grow at 30% per year for the next one year. I’m obviously using extreme example. So that’s recency bias. You take a near term past and assume that’s going to be the same in the long term future. On the other side, let’s say you have a company that over the cycle has barely earned its cost of capital and averaged a dollar per share. But now the last couple of years been earning $2 per share and averaging 20% return on capital. So you are going to extrapolate that $2 and assume that’s the new normalized earnings for the business and say the new long term average earnings is $2. And this now all of a sudden, the 20% return on capital business or something like that.

Gary Mishuris (21:40):

In each case, you’re ignoring the base rate, the base rate in this case being the history of the company or the history of similar companies. So in the first case, the history of companies growing 30% for two years is mean version in the growth rate towards the growth rate in all companies. So just to level set everything that the average company’s profits over long periods of time grow in line with nominal GDP. But, by the way, ironically, if you look at Wall Street estimates, hey, now they assume the average company grow is going to grow earnings in double digits. Well, it hasn’t, it’s been growing five to 6%. And that’s an example of base-rate neglect because they forget that a fifth of the market is going to have negative earnings growth, but that’s a separate thing.

Gary Mishuris (22:20):

And then the base rate for a company that’s been earning its cost of capital and had a couple of good years is that the long term history is much more likely to be the best predictor than the last couple of years, which could be a cyclical high or something like that. So I think ignoring the base rate leads to the recency bias, where we put a disproportionate weight on what just happened and assume that’s a proxy for what’s going to happen as opposed to zooming out and looking at a much longer data series…

…Gary Mishuris (54:36):

And like you said, if you have areas where you don’t invest, that squeezes those 10 to 15 investments into the rest of the opportunity set, meaning that you might be correlated. But it’s not about gig sectors, which is a common misconception. So I’ll give you an example. So prior to starting Silver Ring, I managed a fund at my prior employer and I had two investments. One was SABMiller, which was a beer company, and the second one was Qualcomm. If you are running some bar risk model, and you’re looking at overlap, they’re completely different gig sectors. One is technology, the other is consumer. So no relationship, you’re good, you’re diversified. But the thesis for each one was predicated on rising middle class in emerging markets, meaning people were going to trade up and buy more expensive beer in China and other emerging economies and people were going to trade up to fancier smartphones, which was going to drive demand for Qualcomm’s products.

Gary Mishuris (55:28):

So here are two completely different industries where the same macro force, which is a tailwind, if it doesn’t play out would hurt the thesis. So looking for those correlations as systematically as possible, and thinking about what do I have to be right about each business five plus years out as opposed to what do I have to be right about each stock five quarters out, that’s the mindset you want to have. And also frankly, you have a set of risk reward trade-offs. Too many people make the mistake of sizing their largest investments based on upside. But again, going back to the safety first mentality, I size my positions based on downside, meaning my largest investments have the smallest downside. I have an investment, which maybe it’s a 30% of my base case value as to 30 cents in a dollar, but if that has 100% downside, that might not be my biggest position. So again, you want to have multiple layers of defense.

6. The Transcript Q1 2022 Letter – Scott Krisiloff and Erick Mokaya

Investors are asking whether this is the end of an era. For nearly 15 years global policymakers have battled a deflationary mindset with near-zero interest rates and quantitative easing. However, a series of supply chain shocks and monetary policy errors have sparked rising long-term inflation expectations. If we have exited the deflation era and entered into an inflationary one, it will mean structural changes in monetary policy, interest rates, and stock multiples. By the Fed’s own account, despite raising interest rates by 0.75% so far this year, it is still only on pace to get to a neutral interest rate by the end of the year. It has not yet entered the restrictive territory, which would usually be justified by >8% inflation.

“We’ve been accustomed to 40 years, basically, of one cycle, the whole cycle that we covered in the last quarterly review. Declining interest rates, declining tax rates, all these trends – – it’s all come to an end. Not just an end, it’s actually changing. But people haven’t wrapped their heads around that yet…There’s going to be a new cycle.” – Horizon Kinetics (INFL) Co-Founder Steven Bregman

“An entire generation of entrepreneurs & tech investors built their entire perspectives on valuation during the second half of a 13-year amazing bull market run. The “unlearning” process could be painful, surprising, & unsettling to many. I anticipate denial.” – Benchmark Capital General Partner Bill Gurley

While the Fed has talked about getting to “neutral” throughout this quarter, it hasn’t yet set an expectation for what neutral means. There seems to be some consensus that this neutral rate would be a short-term interest rate in the 2.5% – 3.5% range. Equity markets may not yet reflect this new cost of capital.

“I think I’m in the same areas as my colleagues philosophically. I think it’s really important that we get to neutral and do that in an expeditious way. “ – Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic

“I like to think of it as expeditiously marching towards neutral. It’s clear the economy doesn’t need the accommodation we’re providing. And so in order not to tip the economy over by reacting abruptly, we need to take a measured pace. But that measured pace still gets us up to the neutral rate, which I put at about 2.5% by the end of the year.” – San Francisco President Mary Daly…

…The Transcript is also closely watching continued lockdowns in China. The Chinese government’s zero-Covid policy has left hundreds of millions of people in lockdown even though the rest of the world has returned to normal. The effects of this supply chain shock have still not entirely made their way into the economic discussion.

“I think a separate risk is kind of the impact of logistics and supply chains as we deliver product to China and from a more macro perspective just the port closures and the broader impact that we could see in China given the degree of exports they have just generally across the economy. With respect to the China quota difficult to predict.” – Intuitive Surgical (ISRG) CFO Jamie Samath

“...the situation in China is unprecedented. Shanghai, a city 4x the size of New York City, is completely locked down…China continues to battle COVID resurgences and navigate through prolonged lockdowns.” – Starbucks (SBUX) CEO Howard Schultz…

…Surprisingly, consumer spending has still only been moderately affected by surging inflation and falling financial markets. The covid-era stimulus has left consumer bank accounts with lots of reserves and consumers still have a significant amount of pent-up demand for travel, restaurants, and other entertainment. We are expecting to see some slowing of consumer spending and the real economy going forward in sympathy with the dynamics of capital markets.

“March was the eighth straight month in which inflation outpaced income with lower-income consumers being most impacted by rising energy and food prices.” – Wells Fargo (WFC) CEO Charlie Scharf

“Consumers are trying to ration their money a little bit more carefully because they’re trying to smooth out their cash flow.” – Affirm (AFRM) CEO Max Levchin

“when we think about where inflation is, there’s absolutely pressure on that low and middle income consumer.” – Macy’s (M) CEO Adrian V. Mitchell…

…No one really knows whether this is truly the end of an era and the start of an inflationary epoch, but this period is not without historical analogue. The transition from the deflationary 1930s to the inflationary 1940s was caused by World War II, which was also a time of intense supply chain disruptions coupled with huge economic stimulus. The Covid period has some similarities. Immediately following the war there was sharp and severe inflation for several years, which was ultimately brought under control by changes in monetary policy. In the longer term, huge investment in industrial capacity and human capital led to a consumer renaissance and low inflation in the 1950s.

The inflationary period of 1966-1980 is also worth studying if we are entering a new inflationary phase. An important takeaway from that period is that a surge in interest rates does not necessarily happen overnight. Instead, it happened in fits and starts over the course of several bear markets and recessions. Stock multiples ended that period in single digits, but the nominal value of the Dow hovered around 1,000 for more than a decade.

We may be entering a period in which the Fed raises interest rates more frequently than it lowers them, but the Fed is still very reluctant to cause a recession. If it looks like higher interest rates are putting employment at risk, the Fed is likely to abruptly change course despite inflation. The result would probably be positive for capital market valuations.

“You can’t think of a worse environment than where we are right now for financial assets..I think we’re in one of those very difficult periods where simply capital preservation is I think the most important thing we can strive for. I don’t know if it’s going to be one of those periods where you’re actually trying to make money.” – Tudor Investment Corporation Co-Founder Paul Tudor Jones

7. Trying Too Hard – Morgan Housel

Thomas McCrae was a young 19th Century doctor still unsure of his skills. One day he diagnosed a patient with a common, insignificant stomach ailment. McCrae’s medical school professor watched the diagnosis and interrupted with every student’s nightmare: In fact, the patient had a rare and serious disease. McCrae had never heard of it.

The diagnosis required immediate surgery. After opening the patient up, the professor realized that McCrae’s initial diagnosis was correct. The patient was fine.

McCrae later wrote that he actually felt fortunate for having never heard of the rare disease.

It allowed his mind settle on the most likely diagnosis, rather than be burdened by searching for rare diseases, like his more-educated professor. He wrote: “The moral of this is not that ignorance is an advantage. But some of us are too much attracted by the thought of rare things and forget the law of averages in diagnosis.”

A truth that applies to almost every field is that it’s possible to try too hard, and when doing so you can get worse results than those who knew less, cared less, and put in less effort than you did…

…But there are mistakes that only an expert can make. Errors – often catastrophic – that novices aren’t smart enough to make because they lack the information and experience needed to try to exploit an opportunity that doesn’t exist…

…Marc Andreessen explained how this has worked in tech: “All of the ideas that people had in the 1990s were basically all correct. They were just early.” The infrastructure necessary to make most tech businesses work didn’t exist in the 1990s. But it does exist today. So almost every business plan that was mocked for being a ridiculous idea that failed is now, 20 years later, a viable industry. Pets.com was ridiculed – how could that ever work? – but Chewy is now worth more than $10 billion.

Experiencing what didn’t work in 1995 may have left you incapable of realizing what could work in 2015. The experts of one era were disadvantaged over the new crop of thinkers who weren’t burdened with old wisdom…

…Doctors have their own version, as one article highlights:

“Almost all medical professionals have seen what we call “futile care” being performed on people. That’s when doctors bring the cutting edge of technology to bear on a grievously ill person near the end of life. The patient will get cut open, perforated with tubes, hooked up to machines, and assaulted with drugs. All of this occurs in the Intensive Care Unit at a cost of tens of thousands of dollars a day.

What it buys is misery we would not inflict on a terrorist. I cannot count the number of times fellow physicians have told me, in words that vary only slightly, “Promise me if you find me like this that you’ll kill me.” They mean it. Some medical personnel wear medallions stamped “NO CODE” to tell physicians not to perform CPR on them. I have even seen it as a tattoo.

The trouble is that even doctors who hate to administer futile care must find a way to address the wishes of patients and families. Imagine, once again, the emergency room with those grieving, possibly hysterical, family members. They do not know the doctor. Establishing trust and confidence under such circumstances is a very delicate thing. People are prepared to think the doctor is acting out of base motives, trying to save time, or money, or effort, especially if the doctor is advising against further treatment.”

Disclaimer: None of the information or analysis presented is intended to form the basis for any offer or recommendation. Of all the companies mentioned, we currently have a vested interest in Intuitive Surgical, Meituan, Salesforce, and Starbucks. Holdings are subject to change at any time.