The Key Mindsets We Need To Invest Well - 16 May 2020

Having a good framework to find investment opportunities in the stock market is important. But it’s equally important – perhaps even more important – to have the right mindsets. Without them, it’s hard to be a successful investor even if you have the best analytical mind in the world of finance.

There are six key mindsets that I want to share in this article.

The first mindset

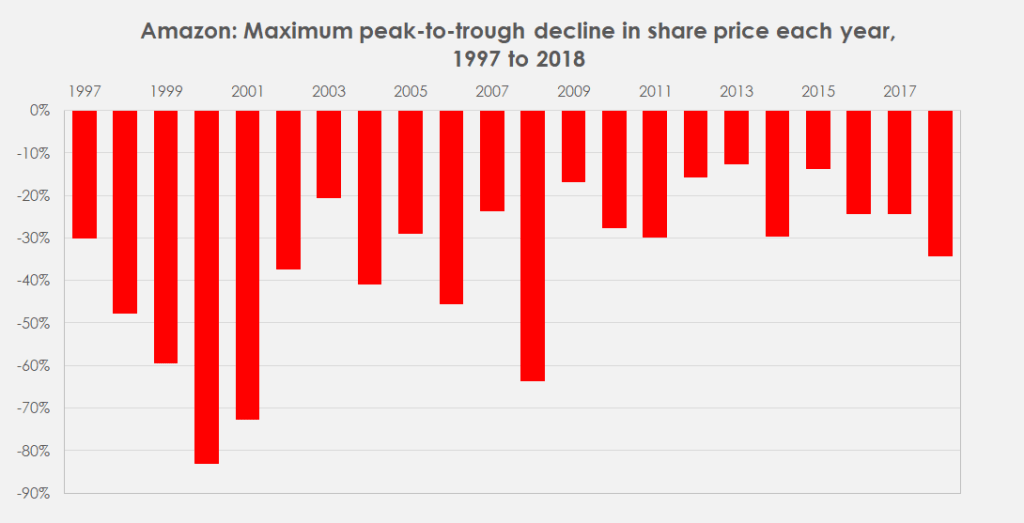

Here’s a chart showing the maximum peak-to-trough decline for Amazon’s share price in each year from 1997 to 2018:

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence

It turns out that Amazon had experienced a double-digit peak-to-trough fall (ranging from 13% to 83%) in its share price in every single year from 1997 to 2018. Looks horrible, doesn’t it?

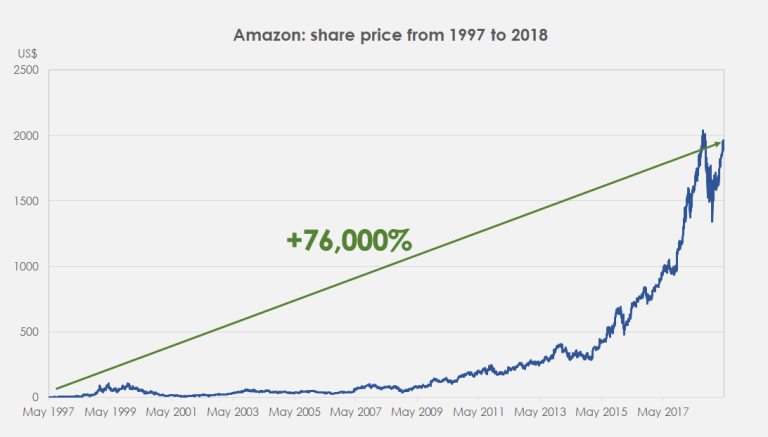

Now here’s a chart showing Amazon’s share price from 1997 to 2018:

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence

The second chart makes it clear that Amazon has been a massive long-term winner, with its share price rising by more than 76,000% from US$1.96 in 1997 to US$1,501.97 in 2018. Amazon does not look so horrible now, does it?

The experience of the e-commerce giant is why Peter Lynch, the legendary fund manager of Fidelity Magellan Fund, once said:

“In the stock market, the most important organ is the stomach. It’s not the brain.”

We need the stomach to withstand volatility, the violent ups-and-downs of share prices. As Amazon has shown, even the best long-term winners in the stock market have suffered from sharp short-term declines.

This is why accepting that volatility in share prices is a feature of the stock market and not a bug is a very important mindset for me. When stocks go up and down, it’s not a sign that something is broken. In fact, there’s actually great data to prove that volatility in share prices do not tell us much about how the underlying businesses are doing.

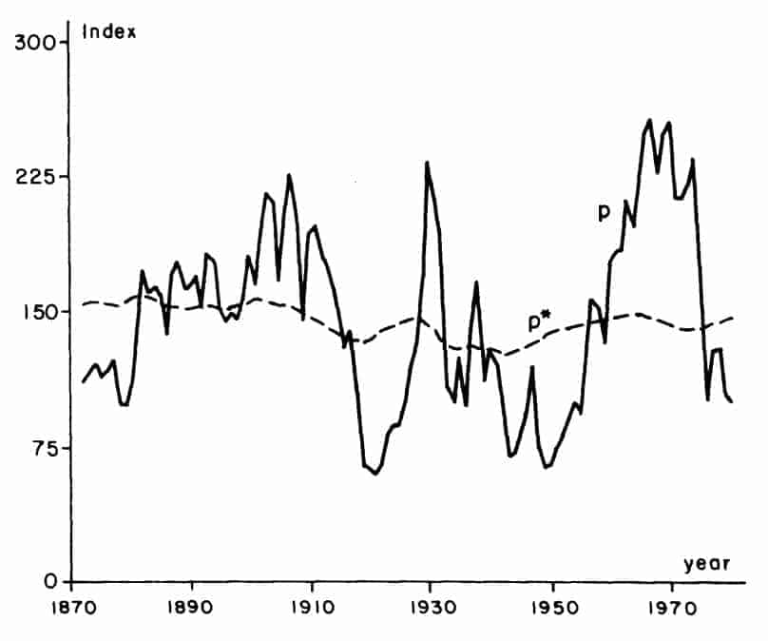

Robert Shiller is an economist who won the Nobel Prize in 2013. In the 1980s, Shiller looked at how the US stock market performed from 1871 to 1979. He compared the market’s actual performance to how it should have rationally performed if investors had hindsight knowledge of how the dividends of US stocks would change. Here’s the chart Shiller plotted from his research:

The solid black line is the stock market’s actual performance while the black dashed line is the rational performance. The fundamentals of American businesses – using dividends as a proxy – was much less volatile than American share prices.

The second mindset

We cannot run from the fact that we humans are emotional creatures. When share prices fall – even with the knowledge that volatility is merely a feature in the stock market – it hurts. And when it hurts, that’s when we make stupid mistakes.

From 1977 to 1990, Peter Lynch earned an annual return of 29% for Fidelity Magellan Fund, turning every thousand dollars invested with him into $27,000. It is this performance that made Lynch a legend in the investing business. But shockingly, the average investor in his fund made only 7% per year – $1,000 invested with an annual return of 7% for 13 years would become just $2,400.

In his book Heads I Win, Tails I Win, Spencer Jakab, a financial journalist with The Wall Street Journal, explained why this big performance-gap happened:

“During his tenure Lynch trounced the market overall and beat it in most years, racking up a 29 percent annualized return. But Lynch himself pointed out a fly in the ointment.

He calculated that the average investor in his fund made only around 7 percent during the same period. When he would have a setback, for example, the money would flow out of the fund through redemptions. Then when he got back on track it would flow back in, having missed the recovery.”

In essence, investors in Fidelity Magellan Fund had bought high and sold low. That’s a recipe for poor returns, born out of our emotional reactions to the stock market’s volatility.

I think there’s a great way for us to frame how we think about volatility so that we can minimise its damage. This was articulated brilliantly by Morgan Housel in a recent blog post of his (emphasis his):

“But a reason declines hurt and scare so many investors off is because they think of them as fines. You’re not supposed to get fined. You’re supposed to make decisions that preempt and avoid fines. Traffic fines and IRS fines mean you did something wrong and deserve to be punished. The natural response for anyone who watches their wealth decline and views that drop as a fine is to avoid future fines.

But if you view volatility as a fee, things look different.

Disneyland tickets cost $100. But you get an awesome day with your kids you’ll never forget. Last year more than 18 million people thought that fee was worth paying. Few felt the $100 paid was a punishment or a fine. The worthwhile tradeoff of fees is obvious when it’s clear you’re paying one.

Same with investing, where volatility is almost always a fee, not a fine.

Returns are never free. They demand you pay a price, like any other product. And since market returns can be not just great but sensational over time, the fee is high. Declines, crashes, panics, manias, recessions, depressions.”

This is why my second mindset is this: Instead of seeing short-term volatility in the stock market as a fine, think of it as a fee for something worthwhile – great long-term returns.

You might be thinking: Is the fee really worth paying? We saw the case of Amazon earlier, where the fee was definitely worth it. Thing is, the point I made about Amazon can actually be applied to the broader US market too.

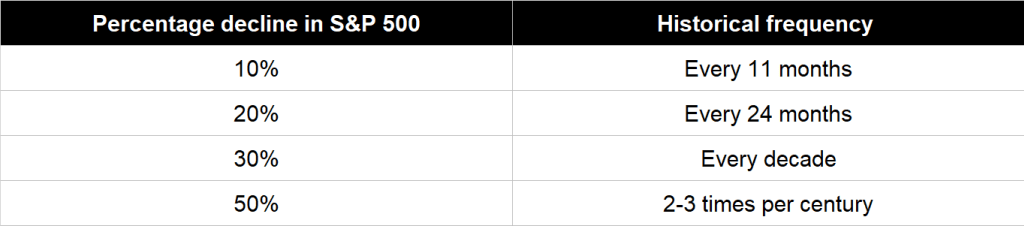

A few years ago, Housel wrote an article for The Motley Fool that showed how often the US stock market – represented by the S&P 500 – had fallen by a certain percentage from 1928 to 2013. Here’re the results:

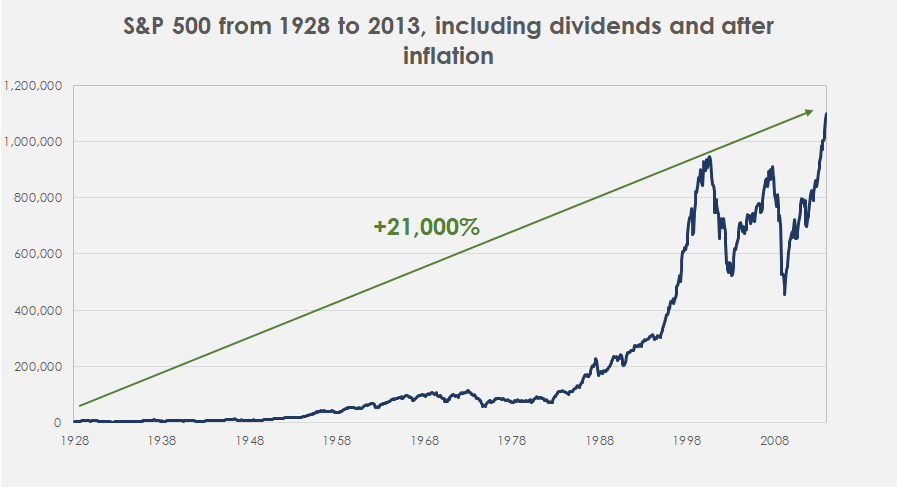

It’s clear that US stocks have declined frequently. But data from Robert Shiller also showed that the S&P 500 was up by around 21,000% from 1928 to 2013 after factoring in dividends and inflation. That means every $1,000 invested in the S&P 500 in 1928 would become $210,000 in 2013 after inflation. The S&P 500 has charged investors an expensive entry fee (in the form of volatility) for a magical show.

Source: Robert Shiller data

The third mindset

A common misconception I encounter about the stock market is that what goes up must come down. Yes it’s true that there’s cyclicality with stocks. But an important point is missed: Stocks go up a lot more than they go down. We’ve seen that with Amazon and with the S&P 500. Now let’s see it with stocks all over the world.

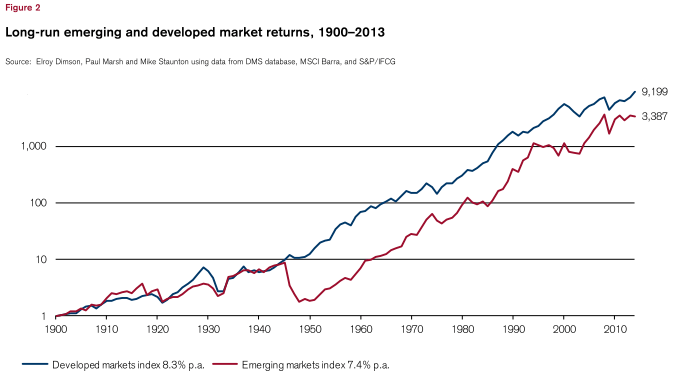

Source: Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2014

The chart above plots the returns of the stock markets from both developed and developing economies over more than 110 years from 1900 to 2013. In that timeframe, stocks in developed economies (the blue line) produced an annual return of 8.3% while stocks in developing economies (the red line) generated a return of 7.4% per year. There are clearly bumps along the way, but the long run trend is crystal clear.

So the third key mindset I have when investing in the stock market is that what goes up, does not always come down permanently. But there is an important caveat to note: Diversification is crucial.

The fourth mindset

Devastation from war or natural disasters. Corrupt or useless leaders. Incredible overvaluation at the starting point. These are factors that can cause a single stock or a single country’s stock market to do poorly even after decades.

We can study a company’s or country’s traits to understand things like the quality of the leaders and valuations. But there’s pretty much nothing we can do when it comes to catastrophes because of mankind or Mother Nature.

This is why my fourth mindset is the importance of diversifying our investments across both geographies and companies.

The fifth mindset

We’re living in uncertain times. Toward the end of 2019, China alerted the World Health Organisation (WHO) about cases of pneumonia amongst its citizens that were caused by an unknown virus. That was the start of what we know today as COVID-19. Many countries in the world – including our home in Singapore – are currently battling to keep their citizens safe from the disease. When faced with uncertainty, should we still invest?

How do you think the US stock market will fare over the next five years and the next 30 years if I tell you that in this year, the price of oil will spike, and the US will simultaneously go to war in the Middle East and experience a recession? We don’t need to guess, because history has shown us.

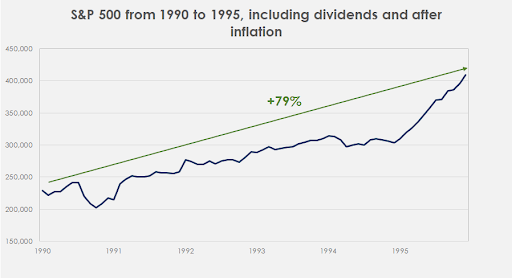

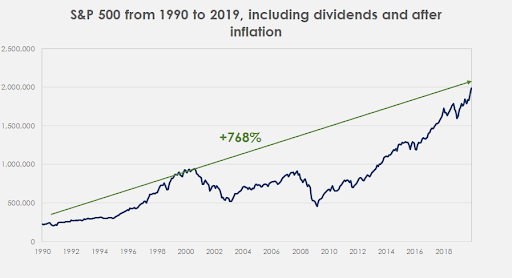

The events I mentioned all happened in 1990. The price of oil spiked in August 1990, the same month that the US went into an actual war in the Middle East. In July 1990, the US entered a recession. Turns out, the S&P 500 was up by nearly 80% from the start of 1990 to the end of 1995, including dividends and after inflation. From the start of 1990 to the end of 2019, US stocks were up by nearly 800%.

Source: Robert Shiller data

What’s also fascinating is that the world saw multiple crises in every single year from 1990 to 2019, as the table below – constructed partially from Morgan Housel’s data – illustrates. Yet, the S&P 500 has steadily marched higher.

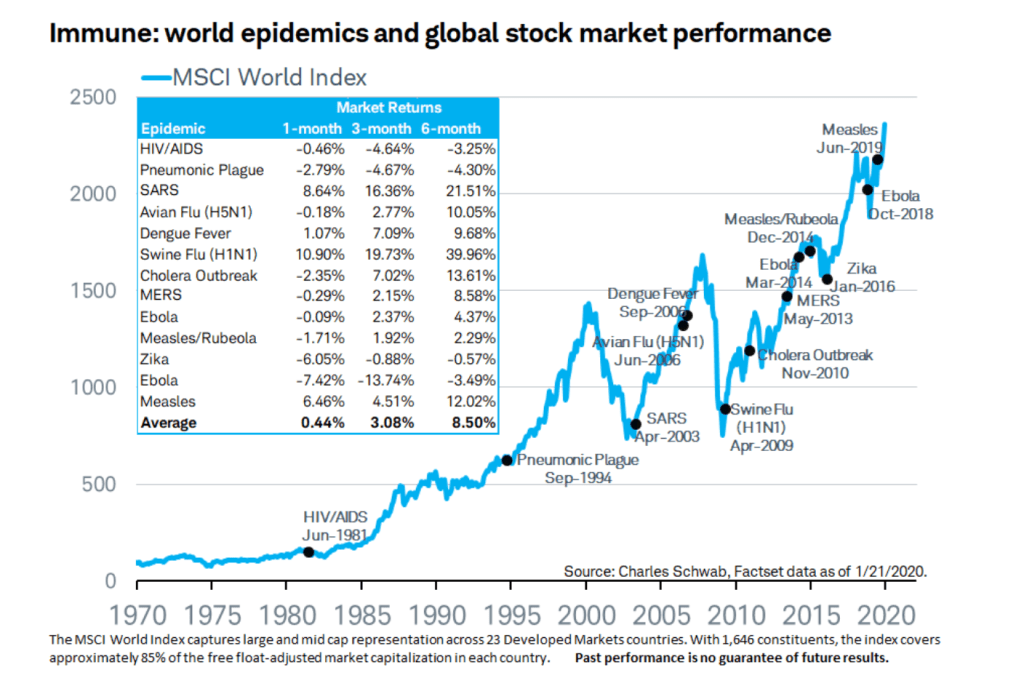

Earlier, I talked about Covid-19. I think it would be appropriate to also show how global stocks have done after the occurence of deadly epidemics.

Source: Marketwatch

The chart just above illustrates the performance of the MSCI World Index (a benchmark for global stocks) since the 1970s against the backdrop of multiple epidemics/pandemics that have happened since. The world has experienced 13 different epidemics since the 1970s. Yet, global stocks – measured by the MSCI World Index – has survived each of those, registering long term gains after each outbreak.

So I carry this important mindset with me (the fifth one): Uncertainty is always around, but that does not mean we should not invest.

The sixth mindset

We’ve seen in the data that market crashes and recessions are bound to happen periodically. But crucially we don’t know when they will occur. Even the best investors have tried to outguess the market, only to fail.

So if we’re investing for many years, we should count on things to get ugly a few times, at least. This is completely different from saying “the US will have a recession in the third quarter of 2020” and then positioning our investment portfolios to fit this view.

The difference between expecting and predicting lies in our behaviour. If we merely expect downturns to happen from time to time while knowing we have no predictive power, our investment portfolios would be built to be able to handle a wide range of outcomes. On the other hand, if we’re engaged in the dark arts of prediction, then we think we know when something will happen and we try to act on it. Our investment portfolios will thus be suited to thrive only in a narrow range of situations – if things take a different path, our portfolios will be on the road to ruin.

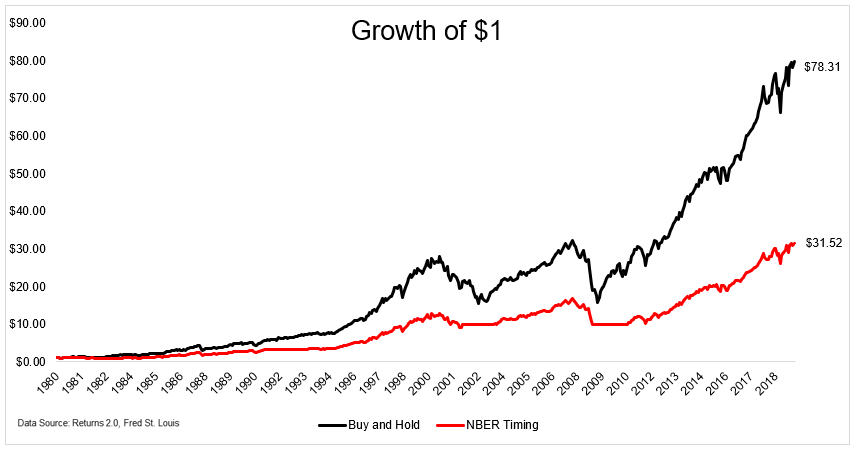

Here’s an interesting thought: If we can just somehow time our stock market entries and exits to coincide with the end/start of recessions, surely we can do better than just staying invested, right?

The chart below is from investor Michael Batnick. The red line shows the return we could have earned from 1980 to today in the US stock market if we had sold stocks at the official start of a recession in the country and bought stocks at the official end. The black line illustrates our return if we had simply bought and held US stocks from 1980 to today. It turns out that completely side-stepping recessions harms our return significantly.

This is why my sixth mindset is that we should expect bad things to happen from time to time, but we should not try to predict them.

In conclusion

To recap, here are the six mindsets that have been very useful for me:

- First, volatility in stocks is a feature, not a sign that something is broken

- Second, think of short-term volatility in the stock market as a fee, not a fine

- Third, what goes up does not always come down permanently

- Fourth, it is important to diversify across geography and companies

- Fifth, uncertainty is always around, but we should still invest

- Sixth, we should expect bad things to happen from time to time in the financial markets, but we shouldn’t try to predict them

They have helped me to be psychologically comfortable when investing. Without them, I may become flustered when things do not go my way temporarily or when uncertainties are rife. This could in turn result in bad investing behaviour on my part. I hope these mindsets can benefit you too.