How we invest

Your understanding of how we’re investing the capital you’ve entrusted to Compounder Fund is of paramount importance. Understanding creates comfort with our process on your part. Understanding also frees us from the time-consuming activity of dealing with queries on our process – this means we have more time to invest better on your behalf!

What Compounder Fund invests in

We will invest Compounder Fund’s capital solely in stocks. Over the past 120 years, stocks have outperformed bonds, bills, currency, and inflation around the world, according to Credit Suisse Research Institute’s Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2020. The stocks we’re investing in for Compounder Fund can come from any stock market in the world (although we will be focusing on stock markets that are in developed economies) as well as from any economic sector. We may also invest in exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that are made up of stocks with similar traits that we’re looking for in individual stocks.

Compounder Fund is a long-only investment fund, meaning we are buying stocks with the view that they will appreciate in price over time.

Here are the constraints we have placed on Compounder Fund:

- The fund’s portfolio will hold 30 to 50 stocks/ETFs at any point in time

- No individual stock or ETF will make up more than 20% of the fund’s assets under management (AUM)

- The fund will not be shorting (to short is to invest with the view that a stock’s price will fall over time)

- The fund will not hedge its positions or use any form of currency hedging

- The fund will not use leverage in any form

- The fund will not invest in financial derivatives

- The fund will have no geographical concentration limit, meaning that up to 100% of Compounder Fund’s capital can be invested in stocks listed in one country’s stock market

- The fund will have no sector concentration limit, meaning that up to 100% of Compounder Fund’s capital can be invested in stocks from just one economic sector

Simply put, Compounder Fund is an investment fund that will be investing only in stocks and/or ETFs around the world. We harbour no illusion that we have any skill in hedging, or currency movements, or leveraging, or financial derivatives. So we do not want to engage in any of these activities and incur unnecessary costs (yes, these activities all cost money!) for Compounder Fund’s investors.

Our investment philosophy

The very first stock market in the world was established in Amsterdam in the 1600s. A few hundred years have passed since, and a stock exchange today looks very different even from just 20 years ago. But one thing has remained constant: A stock market is still a place to buy and sell pieces of a business.

Having this understanding of the stock market leads to the next observation: A stock’s price movement over the long run depends on the performance of its underlying business. In this way, the stock market becomes something easy to grasp: A stock’s price will do well over time if its underlying business does well too.

Berkshire Hathaway, an investment conglomerate run by one of our investment heroes, Warren Buffett, is a great example. From 1965 to 2018, the book value per share (assets per share less liabilities per share) of Berkshire Hathaway grew by 18.7% annually. Over the same period, its stock price increased by 20.5% per year. The 53 years from 1965 to 2018 included the Vietnam War, the Black Monday stock market crash, the “breaking” of the Bank of England, the Asian Financial Crisis, the bursting of the Dotcom Bubble, the Great Financial Crisis, Brexit, and the US-China trade war, among many other crises. But an 18.7% input has still led to a 20.5% output.

We are long-term optimists on the stock market. There are 7.8 billion individuals in our globe today, and the vast majority of people will wake up every morning wanting to improve the world and their own lot in life. This is ultimately what fuels the global economy and financial markets. Miscreants and Mother Nature will occasionally wreak havoc. But we have faith in the collective positivity of humankind. If there’s any mess, humanity can clean it up. To us, investing in stocks is ultimately the same as having faith in the long-term positivity of humankind. We will be long-term optimistic on stocks so long as we continue to have this faith – the exception is when there are ridiculously high valuations in stocks, such as Japan in the late 1980s/early 1990s when stocks there were worth nearly 100 times their 10-year average inflation-adjusted earnings.

Our investment framework

As we mentioned earlier, Compounder Fund will be investing only in stocks – but we’re not investing in just any stock. We will invest the lion’s share of Compounder Fund’s capital in the shares of companies that we call Compounders – hence the name Compounder Fund! Compounders are companies that can compound shareholders’ value over the long run at high rates. In our view, Compounders are companies that excel in all or most of the following six criteria:

1. Revenues that are small in relation to a large and/or growing market, or revenues that are large in a fast-growing market.

This criterion is important because we want companies that have the capacity to grow. Being stuck in a market that is shrinking – such as print-advertising for instance, which declined by 2.3% per year from 2011 to 2018 – would mean that a company faces an uphill battle to grow.

We want companies that are participating in important markets that are powered by long-term, secular trends. We’re not interested in fads (though we may occasionally mistake a fad for a lasting long-term trend).

2. Strong balance sheets with minimal or reasonable levels of debt.

A strong balance sheet enables a company to achieve three things: (1) Invest for growth, (2) withstand tough times, and (3) win market share from weaker competitors during economic turmoil.

Nassim Taleb, author of The Black Swan and Antifragile among other books, classifies organisations and organisms into three categories: Fragile, robust, and antifragile. Fragile things break during times of stress. Robust things remain unchanged. The antifragile though, strengthens as a result of experiencing non-lethal stressful situations. In our view, companies with strong balance sheets exhibit a certain degree of antifragility. We typically look for companies with more cash than debt. If there are significant levels of debt, then we will want high free cash flow.

3. Management teams with integrity, capability, and an innovative mindset.

A management team without capability is bad for self-explanatory reasons. Without an innovative mindset, a company can easily be outgunned by competitors or run out of room to grow. Meanwhile, a management team without integrity can fatten themselves at the expense of shareholders.

These are some of the things we look at to understand how a company’s management team fares on these fronts:

-

-

- How has management’s pay changed over time relative to the company’s business performance? It’s not a good sign if management’s pay has increased or remained the same in periods when the company’s business isn’t doing well.

- How is management compensated? We want management to be compensated based on metrics that make sense to us as the company’s shareholders. We like seeing metrics such as: (a) Growth in free cash flow per share; (b) growth in book value per share; and (c) multi-year changes in the company’s stock price.

- Are there high levels of related-party transactions (RPTs)? RPTs are business transactions made between a company and organisations that are linked to said company’s management. The presence of high levels of RPTs in a company means that management could be using the company to enrich entities that are linked to them.

- Does the company have a good culture? Clues on some companies’ cultures can be found on Glassdoor, a website that allows a company’s employees to rate it anonymously.

- Has the company managed to successfully grow its important business metrics over time?

- Subjective judgement is required when assessing a management team’s ability to innovate. A great example is the US e-commerce and cloud computing giant Amazon. The company started selling just books online when it was founded in 1994 but expanded its online retail business into an incredible variety of product-categories over time. In 2006, the company launched its cloud computing business, AWS (Amazon Web Services), which has since grown into the largest cloud computing service provider in the world.

-

4. Revenue streams that are recurring in nature, either through contracts or customer-behaviour.

Having recurring business is a beautiful thing, because it means a company need not spend its time and money looking to remake a past sale. Instead, past sales are recurring, and the company is free to find brand new avenues for growth.

Recurring revenue from contracts can be in the form of subscriptions. For customer-behaviour, there are two main types. First, there are services or products that the customer has to use or purchase repeatedly – think of how you buy coffee or use your credit card. Second, there are razor-and-blades business models where a company sells you a “razor”. To use the product, you’ll then have to purchase “blades” regularly.

5. A proven ability to grow.

It’s important that a company has shown that it’s able to grow. We think that a strong track record of growth is a good indicator (though not perfect!) on the company’s future growth potential. It’s easy for anyone to promise the sky – delivering on the promise is another matter, and it’s not easy to do.

We’re looking for big jumps in revenue, net profit, and free cash flow over time. Sometimes, just revenue and free cash flow are good enough. We are generally wary of companies that (a) produce revenue and profit growth without corresponding increases in free cash flow, or (b) produce revenue growth but suffer losses and/or negative free cash flow. But we’ll be happy to make exceptions for companies that are generating losses and burning cash in pursuit of growth – if we see that they have a clear path to profitability and strong cash flow production in the years ahead.

6. A high likelihood of generating a strong and growing stream of free cash flow in the future.

The actual value of a company is the amount of cash it can generate over its entire life. So, the more free cash flow a company can generate, the more valuable it is. We will tend to avoid companies with weak free cash flow.

You may notice that there’s no mention of valuation yet. We’re aware that even the best company will be a bad investment if its stock price is too high. We do pay attention to valuations, but the priority in our analysis of a stock is on the quality of its underlying business. We tend to favour simple valuation methods, such as looking at the stock’s price-to-earnings, price-to-free cash flow, price-to-sales, or price-to-book ratios, whichever are appropriate. We will compare the ratios against history and our views on the company’s potential growth.

A small portion of Compounder Fund’s capital could also be invested in stocks that are undergoing special situations or have hidden asset values. In the first category are stocks where step-changes in regulations or market conditions are likely to benefit their businesses in the future. In the second are stocks that hold assets with economic value that are currently not recognised by the market.

In essence, we’re investing based on the strengths of a stock’s business. We will not be investing Compounder Fund’s capital based on predictions about financial markets, stock prices, economies, and politics. We are not good at predicting any of these things, and we don’t think they are necessary for making good investment decisions too. In 1995, Warren Buffett wrote the following:

“We will continue to ignore political and economic forecasts, which are an expensive distraction for many investors and businessmen. Thirty years ago, no one could have foreseen the huge expansion of the Vietnam War, wage and price controls, two oil shocks, the resignation of a president, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, a one-day drop in the Dow of 508 points, or treasury bill yields fluctuating between 2.8% and 17.4%.

But, surprise – none of these blockbuster events made the slightest dent in Ben Graham’s investment principles. Nor did they render unsound the negotiated purchases of fine businesses at sensible prices. Imagine the cost to us, then, if we had let a fear of unknowns cause us to defer or alter the deployment of capital. Indeed, we have usually made our best purchases when apprehensions about some macro event were at a peak. Fear is the foe of the faddist, but the friend of the fundamentalist.

A different set of major shocks is sure to occur in the next 30 years. We will neither try to predict these nor to profit from them. If we can identify businesses similar to those we have purchased in the past, external surprises will have little effect on our long-term results.”

Our portfolio management style

Now that we have the stocks for Compounder Fund, we still need to put them together in a coherent manner. We believe in simplicity when it comes to constructing a portfolio. We analogise portfolio-construction to cooking seafood. If the ingredients (the individual stocks) are fresh and of great quality, the lesser the chef meddles with the ingredients, the tastier the dish (the portfolio) will be. We believe that finding Compounders is the key to achieving good long-term performance for Compounder Fund. We’re designing Compounder Fund to have its long-run return be driven mostly by the underlying business performances of the stocks that it owns.

At the launch of Compounder Fund, we will group the stocks into three baskets based on their level of risk: (1) Stocks with a weight of around 4% or higher; (2) stocks with a weight of around 2.5%; and (3) stocks with a weight of around 1% or lower.

It is our intention to let the winners run in Compounder Fund. What this means is a stock could end up accounting for a growing percentage of Compounder Fund’s total assets over time. To mitigate risk, no single stock can account for more than 20% of Compounder Fund’s AUM, as we mentioned earlier.

Compounder Fund is in the business of investing in the stocks of the best, fastest-growing companies in the world we can find – at reasonable prices – and holding them for a very long time. We believe that the less we meddle with the portfolio, the better Compounder Fund’s long-term result will be. Studies have shown that the more we trade, the lower our returns are. We’re targeting Compounder Fund’s portfolio turnover ratio to be 20% or less. The portfolio turnover ratio is a gauge for the average holding period for a fund’s stocks. A portfolio turnover ratio of 20% or less equates to an average holding period of five years or more. (A 10% portfolio turnover ratio equates to an average holding period of 10 years.) This means that we might appear sloth-like to you in managing Compounder Fund’s capital, since we intend for the fund to hold onto its stocks for a very long period of time. But we need you to understand that the sloth-ness is by design, and not because we’re lazy! As Warren Buffett once said: “The trick is when there is nothing to do, do nothing.”

We intend for Compounder Fund to be nearly fully invested at all times. We will not attempt to time the market by managing the percentage of Compounder Fund’s portfolio that’s in cash. We have no ability to time the market (and only a very rare handful of investors can do it consistently). We think timing the market will mostly be a money-losing exercise. Dimensional Fund Advisors, a large US-based fund management company, once shared the following: (a) $1,000 invested in US stocks in 1970 would become $138,908 by August 2019; (b) miss just the 25 best days in the market (that’s 25 days in nearly 50 years), and the $1,000 would grow to just $32,763. So if you miss just a handful of the market’s best days, your return will plummet. If we run dry of investment ideas for Compounder Fund, we will not allow new subscriptions or top-ups, and if needed, we will return capital to investors.

What happens when Compounder Fund needs to raise cash to meet redemptions from investors? We will have to sell stocks. In such cases, our first candidates for sale are companies in the portfolio with the weakest business performances – we want to sell our losers first. And on the topic of selling stocks, we will typically sell a stock in Compounder Fund’s portfolio if we find that the investment thesis is completely broken, or we have made a big mistake in our analysis. But we will be very slow to sell. The slowness is by design – it strengthens our discipline in holding onto the winners in Compounder Fund. Holding onto the winners will be a very important contributor to Compounder Fund’s long run performance. If Compounder Fund receives new capital from investors, our preference when deploying the capital is to add to our winners and/or invest in new ideas.

How we manage risk

We mentioned earlier that Compounder Fund will own shares in 30 to 50 stocks/ETFs at any point in time. This is to manage risk through diversification while at the same time preventing us from over-diversifying. Some fund managers prefer a more concentrated portfolio, but we prefer to spread our eggs over a wider basket to manage risk. We think it’s crucial for investors to invest in a way that suits their own temperament. We are not comfortable managing a portfolio that only has a handful of stocks.

It’s also important for you to differentiate the concept of volatility and risk. Volatility is the up-and-down movement of stock prices over the short run. It is also how many market participants define risk. But we see risk differently. To us, risk is the chance of permanent or near-permanent loss of capital. And that risk can appear in individual stocks in a few ways:

- Inflation: A runaway increase in prices, which eats away the purchasing power of money.

- Deflation: A persistent drop in asset prices, which have been very rare occurrences throughout world history.

- Confiscation: When authorities seize assets, by onerous taxes or through sheer force.

- Devastation: Because of acts of war, anarchy, and/or natural catastrophes.

- Extreme overvaluation: When stocks carry valuations that are too high at the start.

- Management fraud: When a company fabricates its numbers.

- Bankruptcy: When a company goes bust and its share price falls to zero.

We are not going to manage Compounder Fund’s portfolio to smooth out volatility. So expect Compounder Fund’s portfolio to be volatile. Instead, we are managing Compounder Fund’s portfolio to lower the chances that it will suffer a permanent or near-permanent loss of capital. We do so by being mindful of the various sources of risk we mentioned earlier when we choose the stocks that go into the portfolio. Here’s how we try to handle each source of risk:

- Inflation: Diversify across geography; look for companies with pricing power (so that they can pass on cost-increases to customers) and/or the ability to grow faster than the rate of inflation.

- Deflation: Look for companies with pricing power, so that they can maintain their selling prices in a deflationary environment.

- Confiscation: Invest in markets with relatively stable political regimes and economies, and where the government has a history of respecting the rule of the law and shareholder rights.

- Devastation: For war and anarchy, the actions are the same as for Confiscation; for natural catastrophes, there’s nothing much we can do, unfortunately, beyond geographical and sector diversification.

- Extreme overvaluation: Compare a company’s valuation against history and our views on the company’s potential growth.

- Management fraud: Study the management team deeply and watch out for unusual transactions; diversify, so that even if we end up with frauds, the portfolio can withstand the hit.

- Bankruptcy: Invest in companies that (1) have strong balance sheets, (2) have good ability to generate free cash flow, and (3) are operating in industries with bright prospects.

You might also be wondering how we intend to manage Compounder Fund through bear markets and recessions. We will make no attempt to try and side-step bear markets and recessions because we have no skill in being able to identify these episodes before they happen – we don’t think anyone can do this reliably either. Bear market or no bear market, recession or no recession, our game-plan for Compounder Fund will be the same: We will invest in Compounders and hold their shares for the long run. Bear markets are simply periods of volatility that we don’t see as risk. Some of the traits that Compounders tend to have – robust balance sheets, honest and capable management teams, high levels of recurring revenues, and strong free cash flow – mean that their businesses are well-equipped to survive or even thrive during economic downturns. This protects the true economic value of Compounder Fund’s portfolio over the long run.

You should note the following too:

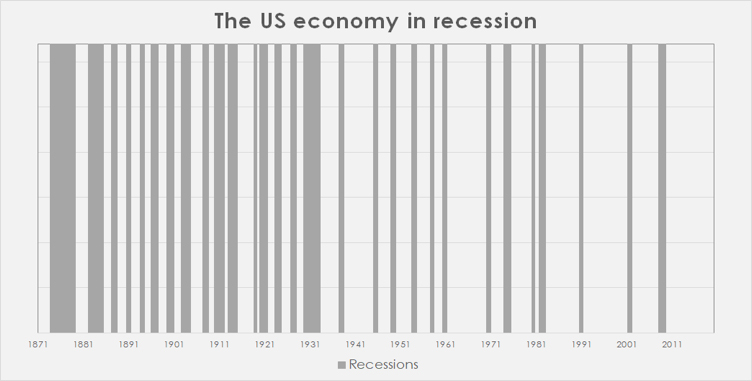

1. Recessions are normal

The chart below shows all the recessions (the dark grey bars) in the US from 1871 to February 2020. You can see that recessions in the country – from whatever causes – have been regular occurrences even in relatively modern times. They are par for the course, even for a mighty economy like the US.

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research

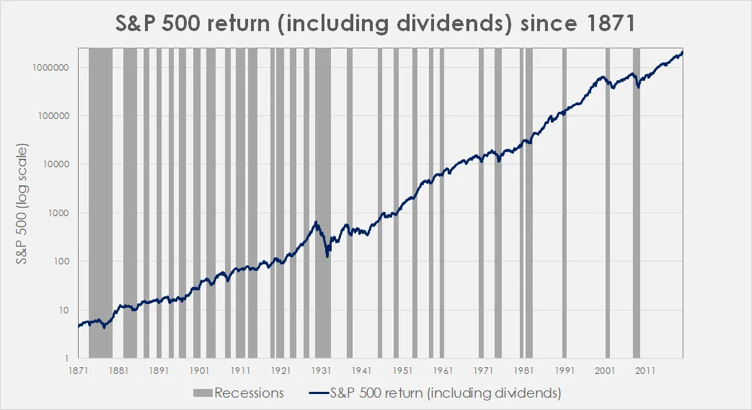

The following logarithmic chart shows the performance of the S&P 500 (including dividends) from January 1871 to February 2020. It turns out that US stocks have done exceedingly well over the past 149 years (up 46,459,412% in total including dividends, or 9.2% per year) despite the US economy encountering numerous recessions. If you’re investing for the long run, recessions are nothing to fear although they can hurt over the short run.

Source: Robert Shiller data; National Bureau of Economic Research

2. The stock market has regularly seen serious short-term losses while on its way to earning great long-term returns

Between 1928 and 2013, the S&P 500 had, on average, fallen by 10% once every 11 months; 20% every two years; 30% every decade; and 50% two to three times per century. So stocks have declined regularly. But over the same period, the S&P 500 also climbed by 283,282% in all (including dividends), or 9.8% per year.

Recessions and volatility in stocks are features of the financial markets, not bugs.

How we find investment ideas

To us, investing involves gathering facts and information, and applying critical and independent thinking. We get our investment ideas from a variety of sources, including: Reading company reports and newsletter subscriptions that highlight important, emerging trends; running screens; and talking to a knowledgeable network of investors and industry-insiders.

Over the many years of our professional and personal investing careers, we have also amassed a sizable mental library of knowledge about public-listed companies.

One thing we won’t do is to depend solely on brokerage reports to make investment decisions. We rarely look at brokerage reports and even if we do, it’s to find facts, not opinions.

How Compounder Fund stands out

Markets are, undoubtedly, more efficient than they used to be. With the internet, anyone can gain access to information that was reserved for privileged investors in the past. This easy access to information has eroded any “informational edge” that privileged investors used to have.

But that does not mean that it is impossible to beat the market. In fact, what the recent past has shown is that stocks are still consistently mispriced. Apple, for instance, one of the largest and most-followed companies in the world, saw its shares sold down in late 2018 due in part to fears over weak iPhone demand. But Apple’s stock price went on to nearly double in 2019, handsomely beating the broader US market. This “miss by a penny, beat by a penny” quarter-by-quarter fixation of many market participants can cause great volatility in stock prices, creating massive price-value mismatches in even the largest companies in the world for patient investors to exploit.

We believe Compounder Fund is set up to take advantage of this. Our focus is on investing in companies with bright long-term growth prospects and whose share prices do not truly reflect their long-term potential. Our investing-goal for Compounder Fund is to earn a good return over the long term. We are not managing the fund to mitigate volatility or temporary drawdowns. We are patient investors. The Owner’s Manual gives you an understanding of our long-term investing approach with Compounder Fund. And this understanding will be a key contributor to your and Compounder Fund’s future investing success. It’s our firm belief that the success of an investment fund depends on whether the fund’s manager and the fund’s investors can form a true partnership that is based on mutual understanding. Let’s work together!

Compounder Fund’s global investment mandate also gives us the opportunity to invest in the best companies around the world. Great companies can be found in all corners of the globe. Having a broad mandate enables us to take advantage of that.

Measuring our performance

There are no guarantees in the financial markets – we only deal with probabilities. We cannot guarantee any return. But our target is an annual return of 12% or more over the long run (a five to seven-year period, or longer) for Compounder Fund’s investors, net of all fees. We need to caution you here: The stock market IS VOLATILE. If the market falls, we fully expect Compounder Fund to decline by a similar magnitude or more. But we believe in the long-term potential of the stock market. Historically, it has been the best asset-class in generating wealth. And by finding Compounders and investing in their shares for the long run, we believe Compounder Fund can do very well for you, as one of its investors, over a multi-year period.

When Warren Buffett was running an investment fund in the 1950s and 1960s, he once wrote (emphasis is ours):

“While I much prefer a five-year test, I feel three years is an absolute minimum for judging performance. It is a certainty that we will have years when the partnership performance is poorer, perhaps substantially so, than the [market]. If any three-year or longer period produces poor results, we all should start looking around for other places to have our money. An exception to the latter would be three years covering a speculative explosion in a bull market.”

We couldn’t agree more with Buffett. We hope that you, as an investor in Compounder Fund, will judge its performance over a three-year period at the minimum.