China’s Future: Thoughts From Li Lu, A China Super Investor - 26 May 2020

This post is my self-directed attempt to translate a Mandarin essay penned by Li Lu that was published in November 2019. The topic of the essay is Li’s review and thoughts on the book The Other Half of Macroeconomics and the Fate of Globalization written by economist Richard C. Koo (Gu Chao Ming).

I want to do this translation for three reasons.

First, Li Lu’s views on China’s economy are worth paying attention to. Many of you likely don’t know who he is, but he’s an excellent investor in China. I have never been able to find Li’s investment track record, but one piece of information that I’ve known for years convinces me of his brilliance: Charlie Munger’s an investor in Li’s fund, and Munger has nothing but praise for it. Munger himself is an incredible investor with a well-documented track record, and he’s the long-time right-hand man of Warren Buffett. In a May 2019 interview with The Wall Street Journal, Munger talked about Li:

“There are different ways to hunt, just like different places to fish. And that’s investing.

And knowing that, of course, one of the tricks is knowing where to fish. Li Lu [of Himalaya Capital Management LLC in Seattle] has made an absolute fortune as an investor using Graham’s training to look for deeper values. But if he had done it any place other than China and Korea, his record wouldn’t be as good. He fished where the fish were. There were a lot of wonderful, strong companies at very cheap prices over there…

…Now, so far, Li Lu’s record [at Himalaya] is just as good with a lot of money as it was with very little. But that is a miracle. It’s no accident that the only outside manager I’ve ever hired is Li Lu. So I’m now batting 1.000. If I try it one more time, I know what will happen. My record will go to hell. [Laughter.]”

Second, I think Li’s essay contains thought-provoking insights from him and Koo on the economic future of the Western world, Japan, and China. These insights are worth sharing with a wider audience. But they are presented in Mandarin, and there are many investors who have little or no knowledge of the language. I am fortunate to have sufficient proficiency in Mandarin to be able to grasp the content (though it was still painful to do the translation!), so I want to pay it forward. This also brings me to the third reason.

Google’s browser, Google Chrome, has a function to automatically translate Li’s Mandarin essay into English. But the translation is not the best and I spotted many areas for improvement.

Before I get to my translation, I want to stress again that it is my own self-directed attempt. So all mistakes in it are my sole responsibility. I hope I’ve managed to capture Li Lu’s ideas well. I’m happy to receive feedback about my translation. Feel free to email me at sj.chong@galileeinvestment.com.

Translation of Li Lu’s essay

This year, the book I want to recommend to everyone is The Great Recession Era: The Other Half of Macroeconomics and The Fate of Globalisation, written by Gu Chao Ming.

The book discusses the biggest problems the world is currently facing. First: Monetary policy. In today’s environment, essentially all the major economies of today – such as Japan, the US, Europe, and China – are oversupplying currencies. The oversupply of these base currencies has reached astronomical levels, resulting in the global phenomena of low interest rates, zero interest rates, and even negative interest rates (in the case of the Eurozone). These phenomena have never happened in history. At the same time, the increase in the currency supply has contributed very little to economic growth. Except for the US, the economies of most of the developed nations have experienced minimal or zero growth. Another consequence of this situation is that each country’s debt level relative to its GDP is increasing; concurrently, prices of all assets, from stocks to bonds, and even real estate, are at historical highs. How long will this abnormal monetary phenomenon last? How will it end? What does it mean for global asset prices when it ends? No one has the answers, but practically all of our wealth is tied to these issues.

Second: Globalisation. The fates of many countries, each at different stages of development, have been intertwined because of the rising trend of globalisation over the past few decades. But global trade and capital flows are completely separate from the monetary and fiscal policies that are individually implemented in each country. There are two consequences to this issue. Firstly, significant conflicts have developed between globalisation and global capital flows on one end, and each country’s economic and domestic policies on the other. Secondly, international relations are increasingly strained. For instance, we’re currently witnessing an escalation of the trade conflict between the US and China. There’s also rising domestic unrest – particularly political protests on the streets – in many parts of the world, from Hong Kong to Paris and Chile. At the same time, far-left and far-right political factions are increasingly dominating the political scene of these countries at the expense of more moderate parties, leading to heightened uncertainties in the world. Under these circumstances, no one can predict the future for global trade and capital flows.

Third: How should each country’s macroeconomic and fiscal policies respond to the above international trends? Should there be differences in the policies for each country depending on the stage of development they are at?

The three problems are some of the most pressing issues the world is facing today. The ability to answer even just one of them will probably be an incredible scholarly achievement – to simultaneously answer all three of them is practically impossible. In his book, Gu Chao Ming provided convincing perspectives, basic concepts, and a theoretical framework with sound internal logic for dealing with the three big problems. I can’t really say that Gu has given us answers to the problems. But at the very least, he provides inspiration for us to think through them. His theories are deeply thought-provoking, whether you agree with them or not.

Now let’s talk about the author, Gu Chao Ming [Richard C. Koo]. He is the Chief Economist of Nomura Research Institute and has had a strong influence on the Japanese government over the past 30 years. I first heard of him tens of years ago, at a YPO international conference held in Japan. He delivered a keynote speech at the event, explaining Japan’s then “lost decade” (it’s now probably a “lost two decades” or even “lost three deacdes”). Gu Chao Ming explained the various economic phenomena that appeared in Japan after its bubble burst. These include zero economic growth, an oversupply of currency, zero interest rates, massive government deficit, high debt, and more. The West has many different views on the causes for Japan’s experience, but a common thread is that they resulted from the failure of Japan’s macroeconomic policies.

Gu Chao Ming was the first to provide a completely opposite viewpoint that was also convincing. He introduced his unique and new economic concept: A balance sheet recession. After the bursting of Japan’s asset-price bubble, the balance sheet of the Japanese private sector (businesses and households) switched from rapid expansion to a mode of rapid contraction – he attributed Japan’s economic recession to the switch. Gu provided a unique view, that driving the balance sheet recession was a radical change in the fundamental goal of the entire Japanese private sector from maximising profits to minimising debts. In such an environment, the first thing the private sector and individuals will do when they receive money is not to invest and expand business activities, but to repay debt – it does not matter how much currency is issued by the government. The sharp decline in Japanese asset prices at that time placed the entire Japanese private sector and households into a state of technical bankruptcy. Because of this, what they had to do, and the way they repaired their balance sheets, was to keep saving and paying off their debts. This scenario inevitably caused a large-scale contraction in the economy. The Japanese experience is similar to the US economic crisis in the 1930s. Once the economy begins to shrink, a vicious cycle forms to accelerate the downward momentum. During the Great Depression in the 1930s, the entire US economy shrank by nearly 46% within a few years.

The Japanese government dealt with the problem by issuing currency on a large scale, and then borrowing heavily to make direct infrastructure investments to digest the massive savings of Japanese residents. Through this solution, the Japanese government managed to maintain the economy at the same level for decades. There’s no growth, but the economy has not declined either. In Gu Chao Ming’s view, the Japan government’s macroeconomic policies were the only right choices. The policies prevented the Japanese economy from experiencing the 46% decline in economic activity that the US did in the 1930s. At the same time, the Japanese private sector was given the time needed to slowly repair their balance sheets. This is why Japan’s private sector and households have gradually returned to normalcy today. Of course, there was a price to pay – the Japanese government’s own balance sheet was hurt badly. Japanese government debt is the highest in the world today. Nonetheless, the Japanese government’s policies were the best option compared to the other choices. At that time, that was the most unique view on Japan that I had come across. Subsequently, my observations on Japan’s economy have also confirmed his ideas to a certain extent.

The Western world was always critical of Japan’s policies. Their stance on Japan started to change only after they encountered the Great Recession of 2008-2009. This is because the Western world’s experience during the Great Recession was very similar to what Japan went through in the late 1980s after its big asset-bubble burst. At the time, prices of major assets in the West were falling sharply, leading to technical bankruptcy for the entire private sector – this was why the subsequent experience for the West was eerily similar to Japan’s. To deal with the problem, the main policy implemented by the key Western countries was the large-scale issuance of currency, and they did so without any form of prior agreement. At the time, the experience of the Great Depression of the 1930s was the main influence on the actions of the central banks in the West. The consensus among the economic fraternity after evaluating the policies implemented to handle the Great Depression of the 1930s was based predominantly on Milton Friedman’s views, that major mistakes were made in monetary policies in that era. Ben Bernanke, the chairperson of the US Federal Reserve in 2008, is a strong proponent of this view. In fact, Bernanke thinks that distributing money from helicopters is an acceptable course of action in extreme circumstances. Consequently, Western governments started issuing currency at a large scale to deal with the 2008 crisis. But the currency issuance did not lead to the intended effect of a rapid recovery in economic growth. The money received by the private sector was being saved and used to repay debts. This is why economic growth remains sluggish. In fact, the economy of the Eurozone is bordering on zero growth; in the US economy, there are only pockets of weak growth.

The first response by Western governments to the problem is to continue with their large-scale currency issuance. Western central banks have even invented a new way to do so: Quantitative easing (QE). Traditionally, central banks have regulated the money supply by adjusting reserves (the most important component of a base currency). After implementing QE, the US Federal Reserve’s excess reserves have grown to 12.5 times the statutory amount. The major central banks in the West have followed the US’s lead in implementing QE, resulting in the selfsame ratio reaching 9.6 times in the Eurozone, 15.3 times in the UK, 30.5 times in Switzerland, and 32.5 times in Japan! In other words, under normal economic conditions, inflation could reach a similar magnitude (for example, 1,250% in the US) if the private sector could effectively deploy newly issued currency. Put another way, if the newly issued currency were invested in assets, it could lead to asset prices rising manifold to reach bubble levels or provide strong stimulus to GDP growth.

But the reality is that economic growth is anaemic while prices for certain assets have been rising. The greatest consequence of this policy is that interest rates are close to zero. In fact, the Eurozone has around US$15 trillion worth of debt with negative rates today. This has caused questions to be raised about the fundamental assumptions underpinning the entire capitalistic market system. At the same time, it has also not produced the hoped-for economic growth. Right now, the situation in Europe is starting to resemble what Japan experienced back then. People are starting to rethink the episode in Japan. Interest in Gu Chao Ming’s viewpoints on Japan and its fiscal policies are being reignited in the important Western countries.

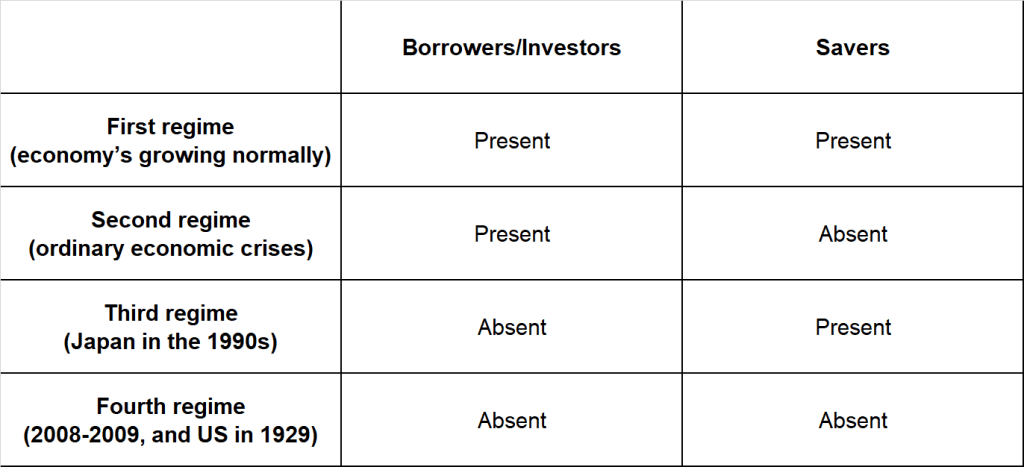

Gu Chao Ming used a relatively simple framework to explain the phenomena in Japan. He said that an economy will always be in one of the following four regimes, depending on the actions of savers and investors:

Under normal circumstances, an economy should have savers as well as borrowers/investors. This places the economy in a positive state of growth. When an ordinary economic crisis arrives, savers tend to run out of capital but borrowers and investing opportunities are still present. In this scenario, it’s crucial that a central bank plays the role of supplier of capital of the last resort. This viewpoint – of the central bank having to be the lender and supplier of capital of the last resort – is the conclusion that the economic fraternity has from studying the Great Depression of the 1930s. Central banks provide the capital, which is then lent to the private sector.

But nobody thought about what happens to an economy when the third and fourth regimes appear. These regimes are unprecedented and characterised by the absence of borrowers (investors). For instance, there have been savers in Japan for the past few decades, but the private sector has no motivation to borrow for investments. What can be done in this case? In the 2008-2009 crisis, there were no savers as well as borrowers in the Western economies. Savers were already absent when the crisis happened. In the US, the private sector was mired in a state of technical bankruptcy because asset prices were falling heavily while there were essentially no savers. At the same time, there were no investment opportunities in Europe. Even after a few rounds of QE and the massive supply of base currencies, nobody was willing to invest – there were simply no opportunities to invest in the economy. When people got hold of capital, they in essence returned the capital to banks via negative interest rates. This situation was unprecedented.

The key contributions to the body of economic knowledge by Gu Chao Ming’s framework relates to a better understanding of what happens in the third and fourth regimes where borrowers are absent. Let’s take Japan for example. It is in the third regime, where there are savers but no borrowers. He thinks that the Japanese government should take up the mantle of being the borrower of last resort in this situation and use fiscal policy to conduct direct investments. A failure to do so will lead to a contraction in the economy, since the private sector is unwilling to borrow. And once the economy contracts, a vicious cycle will form, potentially causing widespread unemployment and economic activity to decline by half. The societal consequences are unthinkable. We know that Hitler’s rise to power in the 1930s and a revival in Japanese militarism in the same era both had direct links to the economic depression prevalent back then.

The fourth regime, one where savers and borrowers are both absent, describes the 2008-2009 crisis. When a fourth regime arises, the government should assume the roles of both provider of capital of last resort, and borrower of last resort. In the US during the 2008-2009 crisis, the Federal Reserve issued currency while the Treasury department used the TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) Act to directly inject capital into systematically important commercial and investment banks. The actions of both the Fed and the Treasury stabilised the economy by simultaneously solving the problems of a lack of savers and borrowers. Till this day, Western Europe is possibly still trapped in the third or maybe even the fourth regime. There are no savers or borrowers. Structural issues in the Eurozone make matters worse. Countries in the Eurozone can only make use of monetary policy, since they – especially the countries in Southern Europe – are restricted from using fiscal policy to boost domestic demand. These constraints within Europe could lead to catastrophic consequences in the future.

Gu Chao Ming used the aforementioned framework to analyse the unique problems facing the global economy today (the appearance of the third and fourth regimes). He also provided his own views on the current economic policies of developed nations.

He considered the following questions: Why did both Western Europe and the US lumber toward asset bubbles? In addition, why were they unable to discover the path that leads to a return to growth (the US did return to growth, but it is anaemic) after their asset bubbles burst? To answer these questions, Gu Chao Ming provided what I think is his second unique perspective, which is meaningful for the China of today. He shared that an economy will have three different stages of development under the backdrop of globalised trade.

Let me first introduce an important concept in development economics – the Lewis Turning Point. In the early days of urban industrialisation, surplus rural workers are constantly attracted by it. But as industrialisation progresses to a certain scale, the surplus of workers in the rural areas now becomes a shortage, leading to the economy entering a state of full employment. This is the Lewis Turning Point, which was first articulated by British economist W. Arthur Lewis in the 1950s.

Gu Chao Ming’s first stage of development refers to the early days of urban industrialisation, before the Lewis Turning Point is reached. The second stage happens when the economy has moved past the Lewis Turning Point and is in a phase where savings, investments, and consumption are all in a state of intertwined growth. This is also known as the Golden Era. In the third stage of development – a unique stage that Gu Chao Ming brought up – the economy enters a state of being chased, after it passes a mature growth phase and becomes an advanced economy. Why does this happen? That’s because investing overseas in developing countries becomes more advantageous as the cost of domestic production reaches a certain level. In the earlier days, the advantages of investing overseas in developing countries are not clear because of cultural and institutional obstacles. But as domestic production costs rises to a certain height, while other countries are simultaneously strengthening their infrastructure to absorb foreign investments, it becomes significantly more attractive to invest overseas compared to domestically. At this point, capital stops being invested in the country, and domestic wages start to stagnate.

In the first stage of development (the pre-Lewis Turning Point phase), owners of capital have absolute control. This is because rural areas are still supplying plenty of labour, and so the labour force is generally in a weak position to bargain and does not have much pricing power. Companies tend to exploit workers when there are many people looking for work.

In the second stage of development (when the economy is past the Lewis Turning Point and enters a mature growth phase), companies need to rely on investing in productivity to raise their output. At the same time, companies need to satisfy the demands of the labour force, such as increasing their wages, improving their working environment, providing them with better equipment, and more. In this stage, economic growth will lead to higher wages, because shortages are starting to appear in the labour supply. A positive cycle will form, where a rise in wages will lead to higher consumption levels, driving savings and investments higher, and ultimately higher profits for companies. During the second stage, nearly every member of society can enjoy the fruits of economic development. Meanwhile, a consumer society led by the middle class will be formed. Living standards for each level in society are improving – wages are rising even for people with low education levels. This is why the second stage of development is also known as the Golden Era.

Changes in society start to appear in the third stage of development. For the labour force, only those in highly-skilled roles (such as in science and technology, finance, and trade etc.) will continue to receive good returns from their jobs. Wages in traditional manufacturing jobs that require low levels of education will gradually decline. Wealth-inequality in society will widen. Domestic economic and investment conditions will deteriorate, and investors will increasingly look to foreign shores for opportunities. At this juncture, GDP growth will rely on continuous improvements in technology. Countries that excel in this area (like the US for example) will continue to enjoy GDP growth, albeit at a low pace; countries with a weaker ability to innovate (such as Europe and Japan) will experience poor economic growth, and investments will shift toward foreign or speculative opportunities.

Gu Chao Ming thinks that the Western economies had entered the third stage of development in the 1970s. Back then, they were being chased mainly by Japan and Asia’s Four Dragons. Fast forward to the 1980s and China had started to open itself to the international economy while Japan entered the phase of being chased. While being chased, a country’s domestic economic growth opportunities tend to decrease sharply. At the same time, any pockets of economic growth tend to form into frothy bubbles. It was the case in Japan, the US, and Western Europe. Capital flowed into real estate, stocks, bonds, and financial derivatives, forming massive bubbles and their subsequent bursting. Even after a bubble bursts, the country’s economic growth opportunities and potential remain extremely limited. As a result, the economy’s ultimate goal shifts from maximising profits to minimising liabilities. That’s because on one hand, the private sector has nowhere to invest domestically, while on the other, it wants to repair its balance sheet. In this way, predictions that are based on traditional economic theories will fail.

Gu Chao Ming pointed out that the functions of a government’s macro policies should change depending on what stage of development the economy is at. And so, different policy tools are needed. This view has meaningful implications for China today.

In the early phases of industrialisation, economic growth will rely heavily on manufacturing, exports, and the formation of capital etc. At this juncture, the government’s fiscal policies can play a huge role. Through fiscal policies, the government can gather scarce resources and invest them into basic infrastructure, resources, and export-related services etc. These help emerging countries to industrialise rapidly. Nearly every country that was in this stage of development saw their governments implement policies that promote active governmental support.

In the second stage of development, the twin engines of economic growth are rising wages and consumer spending. The economy is already in a state of full employment, so an increase in wages in any sector or field will inevitably lead to higher wages in other areas. Rising wages lead to higher spending and savings, and companies will use these savings to invest in productivity to improve output. In turn, profits will grow, leading to companies having an even stronger ability to raise wages to attract labour. All these combine to create a positive feedback loop of economic growth. Such growth comes mainly from internal sources in the domestic economy. Entrepreneurs, personal and household investing behaviour, and consumer spending patterns are the decisive players in promoting economic growth, since they are able to nimbly grasp business opportunities in the shifting economic landscape. Monetary policies are the most effective tool in this phase, compared to fiscal policies, for a few reasons. First, fiscal policies and private-sector investing both tap on a finite pool of savings. Second, conflicts could arise between the private sector’s investing activities and the government’s if poorly thought-out fiscal policies are implemented, leading to unnecessary competition for resources and opportunities.

When an economy reaches the third stage of development (the stage where it’s being chased), fiscal policy regains its importance. At this stage, domestic savings are high, but the private sector is unwilling to invest domestically because the investing environment has deteriorated – domestic opportunities have dwindled, and investors can get better returns from investing overseas. The government should step in at this juncture, like what Japan did, and invest heavily in infrastructure, education, basic research and more. The returns are not high. But the government-led investments can make up for the lack of private-sector investments and the lack of consumer-spending because of excessive savings. In this way, the government can protect employment in society and prevent the formation of a vicious cycle of a decline in GDP. In contrast, monetary policy is largely ineffective in the third stage.

For China’s current development, discussions on the use of macro policies are particularly meaningful. Although there are different viewpoints, the general consensus is that China had passed the Lewis Turning Point a few years ago and entered a mature growth phase. Over the past decade, we’ve seen accelerating growth in the level of wages, consumer spending, savings, and investments. But even when an economy has entered a new stage of development, the economic policies that were in place for the previous stage of development – and that have worked well – tend to remain for some time. The lag in the formulation and implementation of new policies that are more appropriate for the current stage of development comes from the inertia inherent in government bodies. This mismatch between macro policies and the stage of development the economy is at has happened in all countries and stages. For instance, Western economies are still stuck with macro policies that are more appropriate for the Golden Era (fiscal policy). Actual data show that the current policies in the West have worked poorly. Today, many Western countries (including Japan) are issuing currencies on a large scale and have zero or even negative interest rates. But even so, these countries are still facing extremely low inflation and slow economic growth while debt levels are soaring.

In the same vein, China’s government is still relying heavily on policies that are appropriate for the first stage of development even when the country’s economy has grown beyond the Lewis Turning Point. In the past few years, we have seen a series of measures for economic reforms. Their intentions are noble, meant to fix issues that have resulted from the industrialisation and manufacturing boom that occured in the previous development stage. But in practice, the reform measures have led to the closures and bankruptcies of private enterprises on a large scale. So from an objective standpoint, the reform measures have, at some level, produced the phenomenon of an advance in the state’s fortunes, but a decline for the private sector. More importantly, it has hurt the confidence of private enterprises and caused a certain degree of societal turmoil and loss of consumer-confidence. All of these have lowered the potential for economic growth in this stage.

Today, net exports contribute negatively to China’s GDP growth while consumption has a share of 70% to 80%. Private consumption is particularly important within the consumption category, and will be the key driver for China’s future economic growth. In the Golden Era, the crucial players are entrepreneurs and individual consumers. The focus and starting point for all policies should be on the following: (1) strengthening the confidence of entrepreneurs; (2) establishing market rules that are cleaner, fairer, and more standardised; (3) reducing the control that the government has over the economy; and (4) lowering taxes and economic burdens. Monetary policy will play a crucial role at this juncture, based on the experiences of many other developed countries during their respective Golden Eras.

During the first stage of development, China’s main financial policy system was based on an indirect financing model. It’s almost a form of forced savings on a large scale, and relied on government-controlled banks to distribute capital (also at a large scale) at low interest rates to manufacturing, infrastructure, exports and other industries that were important to China’s national interests. This financial policy was successful in helping China to industrialise rapidly.

At the second stage of development, the main focus should be this: How can society’s financing direction and methods be changed from one of indirect financing in the first stage to one of direct financing, so that entrepreneurs and individual consumers have the chance to play the key borrower role? We’ve seen such changes happen to some extent in the past few years. For instance, the area of consumer credit has started developing with the help of fintech. There are still questions worth pondering for the long run, such as whether property mortgages can be done better to unleash the potential for secondary mortgages. During this stage, some of the most important tools in macro policy include: Increasing the proportion of direct financing in the system; enhancing the stock market’s ability to provide financing for private enterprises; and establishing bond and equity markets. In addition, the biggest tests for the macro policies are whether the government can further reduce its power in the economy and switch its role from directing the economy to supporting and servicing it.

Over the past few years, the actual results of China’s macro policies have been poor despite the initial good intentions when they were implemented. This is because the policies were simply administrative means. The observation of the economic characteristics of China’s second stage of development also gives us new perspectives and lessons. During the Golden Era of the second stage of development, some policies could possibly have better results if they were adjusted spontaneously by market forces. In contrast, directed intervention may do more harm than good. These are the most important subjects for China today.

Currently, Japan, Western Europe and the US are all in the third stage of development while China is in the second. This means that China’s potential for future growth is still strong. China’s GDP per capita of around US$10,000 is still a cost-advantage for developed nations in the West. At the same time, other emerging countries (such as India) have yet to form any systemic competitive advantages. It’s possible for China to remain in the Golden Era for an extended period of time. China’s GDP per capita is around US$10,000 today, but there are already more than 100 million people in the country that have a per-capita GDP of over US$20,000. These people mainly reside in the southeast coastal cities of the country. China actually does not require cutting-edge technology to help its GDP per capita make the leap from US$10,000 to US$20,000 – all it needs is to allow the living standards and lifestyles of the people in the southeast coastal cities to spread inward throughout the country. The main driver for consumption growth is the “neighbour effect” – I too want for myself what others eat and possess. Information on the lifestyles of the 100 million people in China’s southeast coastal cities can be easily disseminated to the rest of the country’s 1 billion-plus population through the use of TV, the internet, and other forms of media. In this way, China’s GDP per capita can reach US$20,000.

In the years to come, the level of China’s wages, savings, investments, and consumption will all increase and create a positive cycle of growth. Investment opportunities in the country will also remain excellent. Attempts to unleash the growth potential in China’s economy would benefit greatly if China’s government can learn from the monetary policies of the Western nations when they were in their respective Golden Eras, and make some adjustments to the relationship between itself and the market. Meanwhile, Western nations (especially Western Europe) could learn from the positive experiences of the fiscal policies of Japan and China, and allow the government to assume the role of borrower of last resort and invest in infrastructure, education, and basic research at an even larger scale. Doing so will help developed nations in the West to maintain economic growth while they are in the third stage of development (of being chased).

The idea of adjusting policies and tools as the economy enters different stages of development is a huge contribution to the world’s body of economic knowledge. Economics is not physics – there are no everlasting axioms and theories. Economics requires the study of constantly-changing economic phenomena in real life to bring forth the best policies for each period. From this viewpoint, the theoretical framework found in Gu Chao Ming’s book is a breakthrough for economic research.

Earlier, I mentioned three big questions that the world is facing today and that the book is trying to answer. They are the most intractable and pressing issues, and it is unlikely that there will be perfect answers. Gu Chao Ming has a deep understanding of Japan, so the views found in his book stem from his knowledge of the country’s economic history. But is Japan’s experience really applicable for Europe and the US? This remains to be seen. QE, currency oversupply, zero and negative interest rates, high asset prices, wealth inequality, the rise of populist politics – these phenomena that arose from developed countries will continue to plague policy makers and ordinary citizens in all countries for a long period of time.

For China, it has passed the Lewis Turning Point and is in the Golden Era. The economic policies (particularly the fiscal policies) implemented by Japan and other developed countries in the West during their respective Golden Eras represent a rich library of experience for China to learn from. It’s possible for China to unleash its massive inherent economic growth potential during this Golden Era, so long as its policymakers know clearly what stage of development the country is at, and make the appropriate policy adjustments. China’s future is still promising.