Compounder Fund: Hingham Institution of Savings Investment Thesis - 02 Feb 2023

Data as of 30 January 2023

Hingham Institution of Savings (NASDAQ: HIFS), which is based and listed in the USA, is a company in Compounder Fund’s portfolio that we invested in for the first time in December 2022. This article describes our investment thesis for the company.

Company description

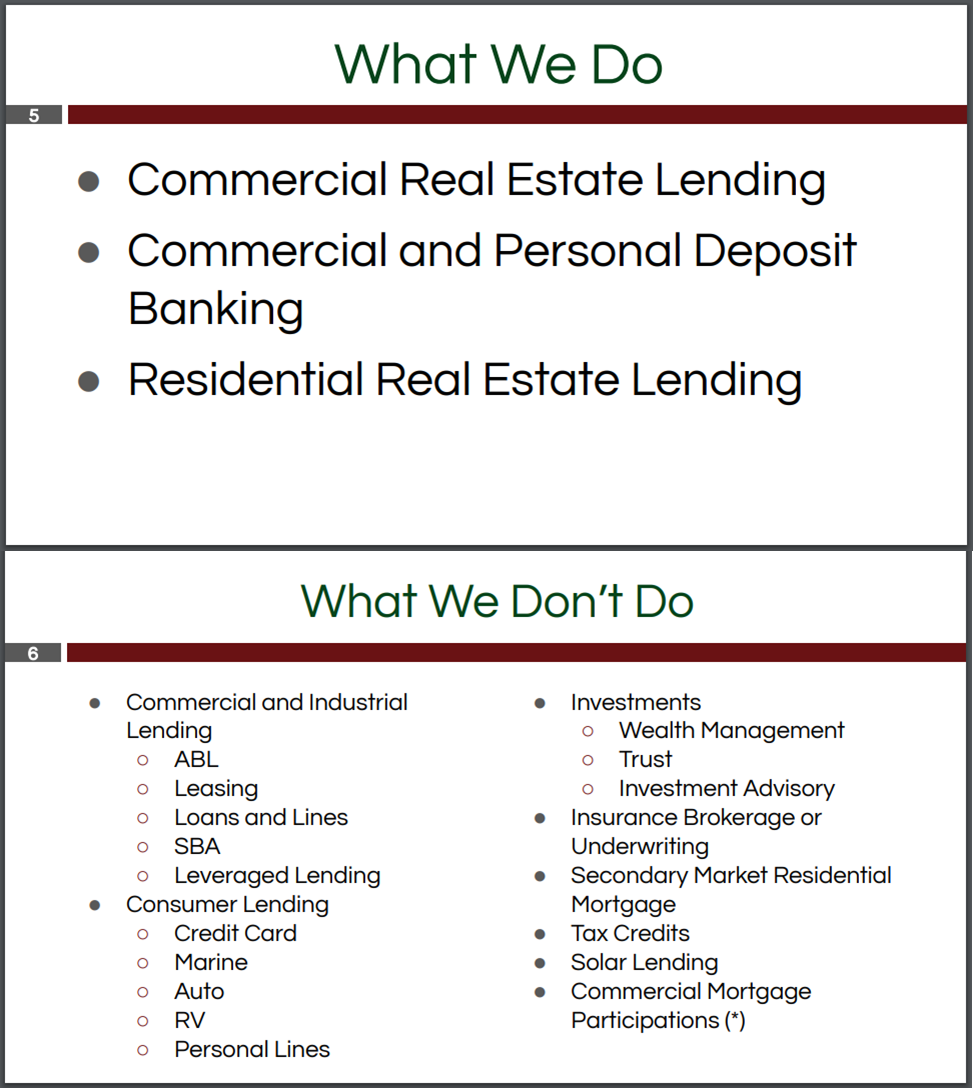

Founded in 1834 in the town of Hingham, Massachusetts, Hingham Institution of Savings (from here on referred to as “Hingham”), is one of the oldest banks in the USA. It’s also one of the most interesting banks we’ve come across. But it’s not the bank’s impressive longevity that caught our eye – rather, it was Hingham’s extremely simple business that flows from its management team’s remarkable focus. The Hingham of today, which is still based in Massachusetts, principally engages in only three banking activities: (1) Commercial real estate lending, (2) residential real estate lending, and (3) deposit services for businesses and consumers. Figure 1 below, which is from Hingham’s presentation deck for its most recent annual shareholder’s meeting held in April 2022, shows what the bank does and does not do.

Figure 1; Source: Hingham April 2022 annual shareholders’ meeting

Hingham operates only in the USA, and specifically only in three markets in the country: Massachusetts, the Washington D.C. Metropolitan Area (WMA), and the San Francisco Bay Area (SFBA). Hingham’s net loans were US$3.66 billion at the end of 2022. But granular details on its loans are only available in its 10-K (the 10-K is an annual regulatory filing US-listed companies have to produce that describes their business activities) and the 2022 10-K will only be available in early-March 2023. So we will break down Hingham’s loans using information for 2021. Massachusetts was Hingham’s primary market in 2021, accounting for 77.5% of the bank’s total loans (before allowance for loan losses, and before deferred loan origination costs) of US$3.02 billion at the end of the year; WMA and SFBA took up 21.5% and 1.0%, respectively. Nearly all of these loans (99.9%) are related to real estate and they belong to a few categories with the important ones being in the following list (Table 1 below shows a detailed breakdown of Hingham’s total loans for 2021):

- Commercial real estate loans: These consist of mortgage loans for the “refinancing, acquisition, or renovation of existing commercial real estate properties such as apartments, offices, manufacturing and industrial complexes, small retail properties, various special purpose properties, and land.” It’s worth noting that the focus of Hingham’s commercial real estate lending is centred on commercially-run properties that are used for residential purposes; such properties include multifamily properties, one-to-four family residential properties, and mixed used properties. (In the American context, a multifamily property is a residential building with more than one dwelling-residence in the same building; multifamily properties in the USA are also often owned by commercial entities that rent out the units to residents for income)

- Residential real estate loans: These include qualified and non-qualified mortgages on owner-occupied one-to-four family residential properties (qualified mortgages are essentially standard mortgage loans while non-qualified mortgages are loans made to borrowers with more unique financial situations). Hingham generally holds onto all the residential real estate loans it originates because management wants the freedom to restructure loans as and when needed to support the needs of the bank’s borrowers. The residential real estate loans that Hingham provides also includes HELOCs (home equity line of credit), which are loans borrowed against the equity of homes (a home’s equity is the difference between its market value and its outstanding mortgage).

- Construction loans: These are mostly for the construction of “residential real estate for owner-occupants, speculative sale, and long-term investment.”

Table 1; Source: Hingham annual report

Around 2013 to 2014, Hingham’s management started investing the bank’s capital in stocks. As of 31 December 2022, Hingham’s portfolio of stocks was worth US$55.0 million, which is 14.2% of the bank’s book value of US$386.0 million, and 1.3% of the bank’s total assets of US$4.19 billion. For context, Hingham’s net loans at end-2022 was US$3.66 billion, as mentioned earlier, which is 87.2% of the bank’s total assets.

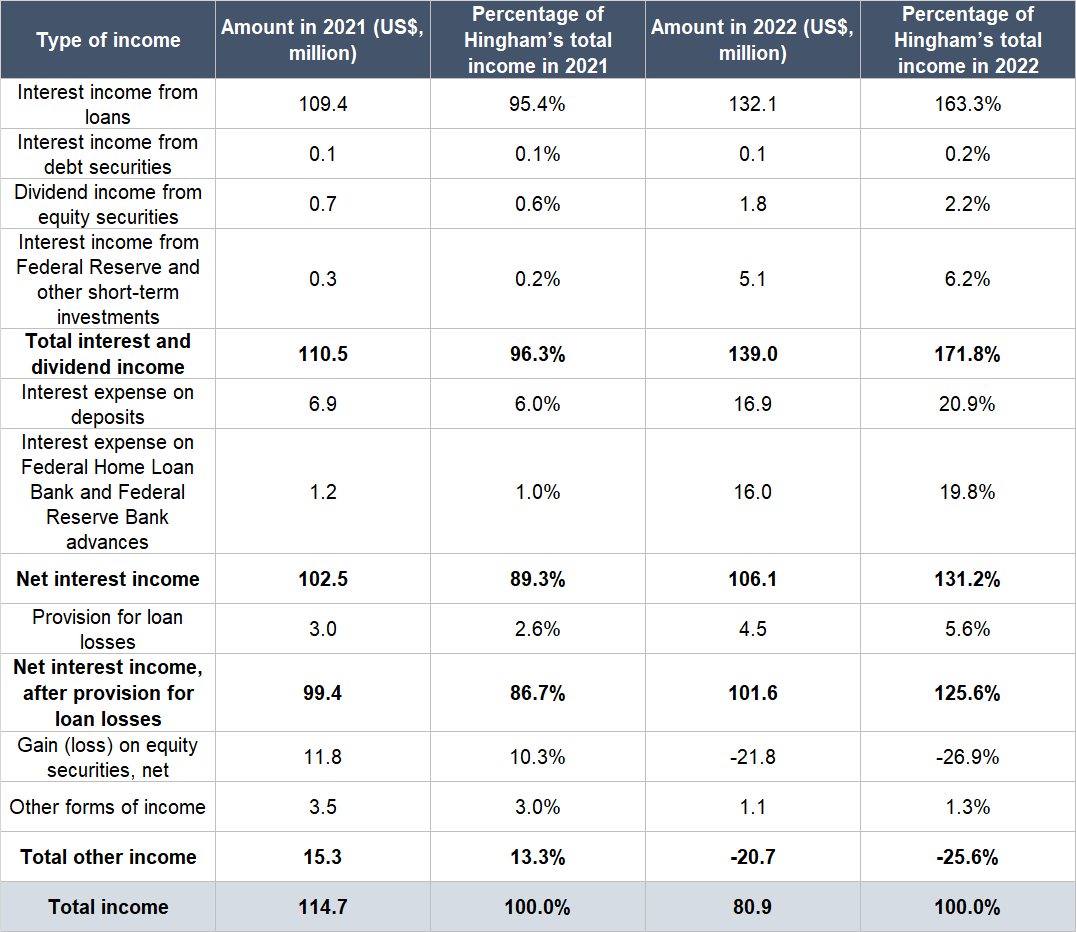

Table 2; Source: Hingham earnings update

Since Hingham’s business activities are centred on lending, it’s not surprising that the lion’s share of its total income (the term used to describe a bank’s revenue) comes from its lending operations. Table 2 above shows the various sources of Hingham’s total income in 2021 and 2022. It’s worth noting that Hingham counts the gains and losses on its portfolio of stocks within its total other income. This means that Hingham’s total income in any given year or quarter will be affected by stock market fluctuations in that timeframe and is thus not entirely reflective of the performance of the bank’s core business of lending. For this reason, we prefer to look at Hingham’s net interest income instead of total income when we assess Hingham’s “revenue”.

Investment thesis

We have laid out our investment framework in Compounder Fund’s website. We will use the framework to describe our investment thesis for Hingham.

1. Revenues that are small in relation to a large and/or growing market, or revenues that are large in a fast-growing market

In this criterion, we’re trying to assess a company’s room for growth. For most types of businesses, we look at their revenues in relation to their market opportunity in making this assessment. But since Hingham is a bank, we think it makes sense to look at the volume of its loans when assessing its market opportunity, since it would be the quantity of loans Hingham makes that would determine its “revenue,” or net interest income.

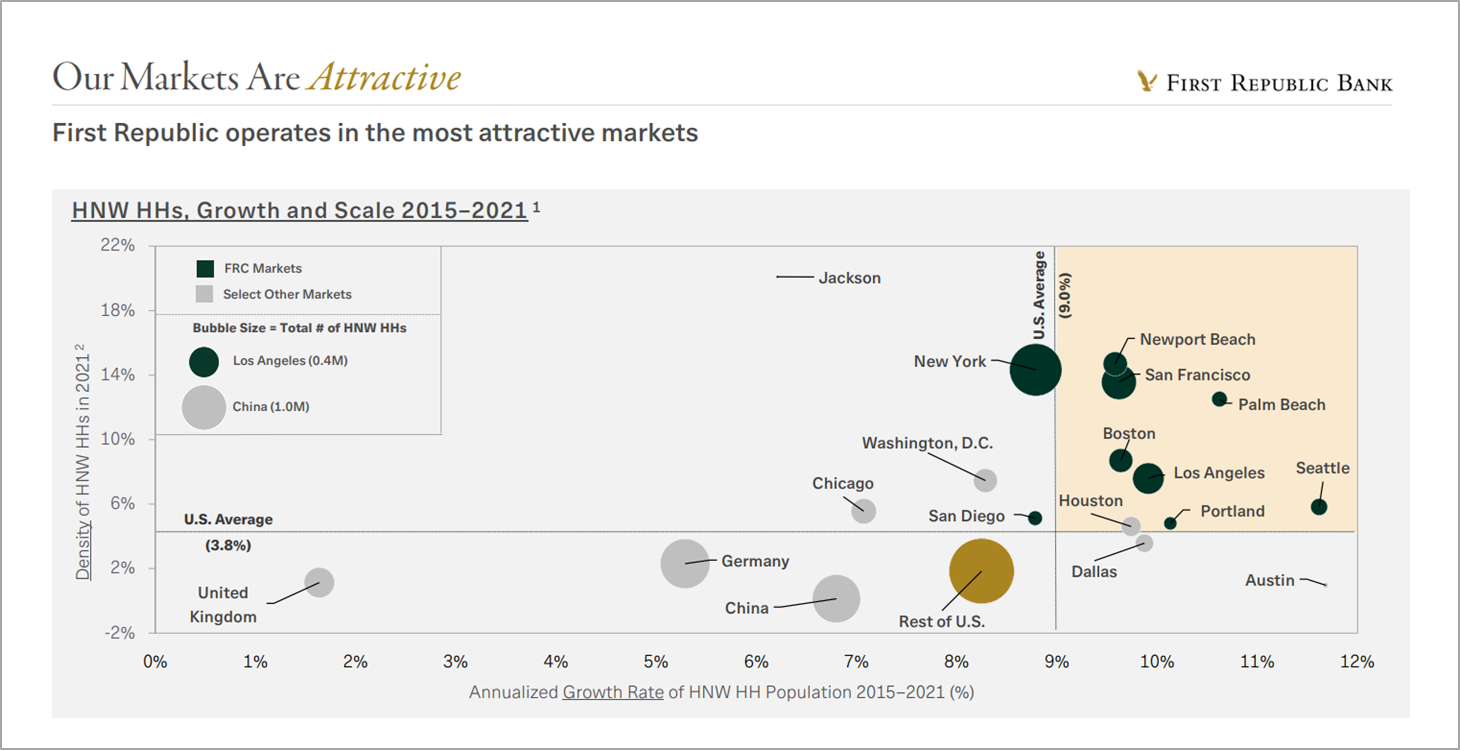

We first mentioned in the “Company description” section of this article that Hingham ended 2022 with net loans of US$3.66 billion. This is merely a drop in the ocean in the US banking market. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is an American agency that insures and supervises US banks. For perspective, as of 30 September 2022, all US banks insured by the FDIC had total loans of US$12.0 trillion. These loans include (a) one-to-four family residential mortgages of US$2.4 trillion, (b) real estate construction and development loans of US$447.3 billion, and (c) home equity loans of US$270.6 billion. It’s worth noting too that Hingham’s three geographical markets in the USA – Massachusetts (where Boston is the state capital), Washington, and San Francisco – have fast-growing and dense affluent populations. This is shown in Figure 2 below, from First Republic Bank, a well-run San Francisco-based bank that also counts loans for residential-related real estate as a key product-line.

Figure 2; Source: First Republic Bank 2022 November Investor Day (HNW HHs refers to “high net worth households”)

2. A strong balance sheet with minimal or a reasonable amount of debt

Since Hingham is a bank, we’re looking at the leverage ratio, which is the ratio of total assets to shareholders’ equity, to assess the strength of its balance sheet. The lower the leverage ratio, the higher the percentage of the bank’s assets that is being funded directly by shareholders’ equity, and the sturdier its balance sheet.

At the end of 2022, Hingham had total assets of US$4.19 billion and shareholders’ equity of US$386.0 million, which gives it a leverage ratio of just 10.9. We think this is a healthy leverage ratio. It is also identical to the US banking industry’s leverage ratio as of 30 September 2022.

3. A management team with integrity, capability, and an innovative mindset

On integrity

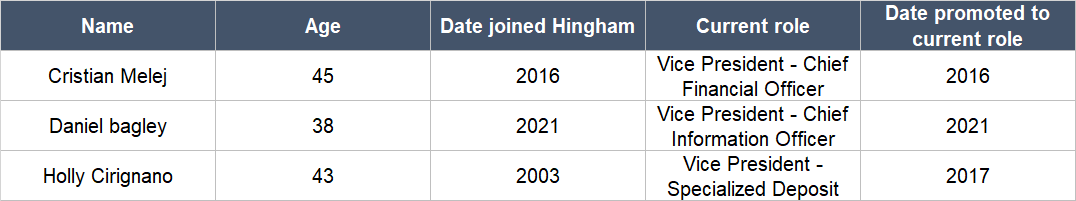

In 1993, Robert Gaughen won a proxy battle to unseat Hingham’s then-leaders after they had mismanaged the bank for years. After the victory, his son, Robert Gaughen Jr, became Hingham’s Chairman and CEO in the same year and he has been in both roles since. The 74-year old Guaghen Jr is aided by his son, Patrick Gaughen, 42, who joined Hingham in 2012 as its Chief Strategy/Corporate Development Officer. Patrick Gaughen was promoted to his current roles of President and Chief Operating Officer in 2018. Table 3 below shows the other key members of Hingham’s management team and a few positive traits about them: They are all young, and two of them have at least seven years of experience each with the bank.

Table 3; Source: Hingham 2022 Proxy Statement

We find Hingham’s compensation structure for its key executives to be thoughtfully constructed. When viewed in totality, it also showcases the integrity of the management team. Here are the key traits of Hingham’s compensation structure:

- The remuneration of the executives consists primarily of an annual base salary.

- Hingham’s Compensation Committee, which consists of three directors (there will be a deeper discussion on the bank’s directors shortly), does not believe that short-term changes in the bank’s performance drives its underlying intrinsic value. As such, the Compensation Committee has limited short-term bonuses for executives and plans to eliminate the bonuses in the future. Moreover, Robert Gaughen Jr, Patrick Gaughen, and Cristian Melej do not receive bonuses.

- The annual compensation of Hingham’s key executives depend on the bank’s “current and long-term return on assets, return on equity, increases in book value per share and dividends declared, and operational efficiency.” In our view, these are sensible metrics for determining management’s compensation. But details about the relationship between the level of compensation and the actual numerical values the metrics need to reach are not publicly available, as far as we can tell; ideally, we would like to know the details.

- Table 4 below shows that Robert Gaughen Jr and Patrick Gaughen’s total compensation in each year from 2019 to 2021 was significantly lower than Hingham’s net income, and their changes in compensation were also lower than the growth in the bank’s diluted earnings per share.

Table 4; Source: Hingham Proxy Statements

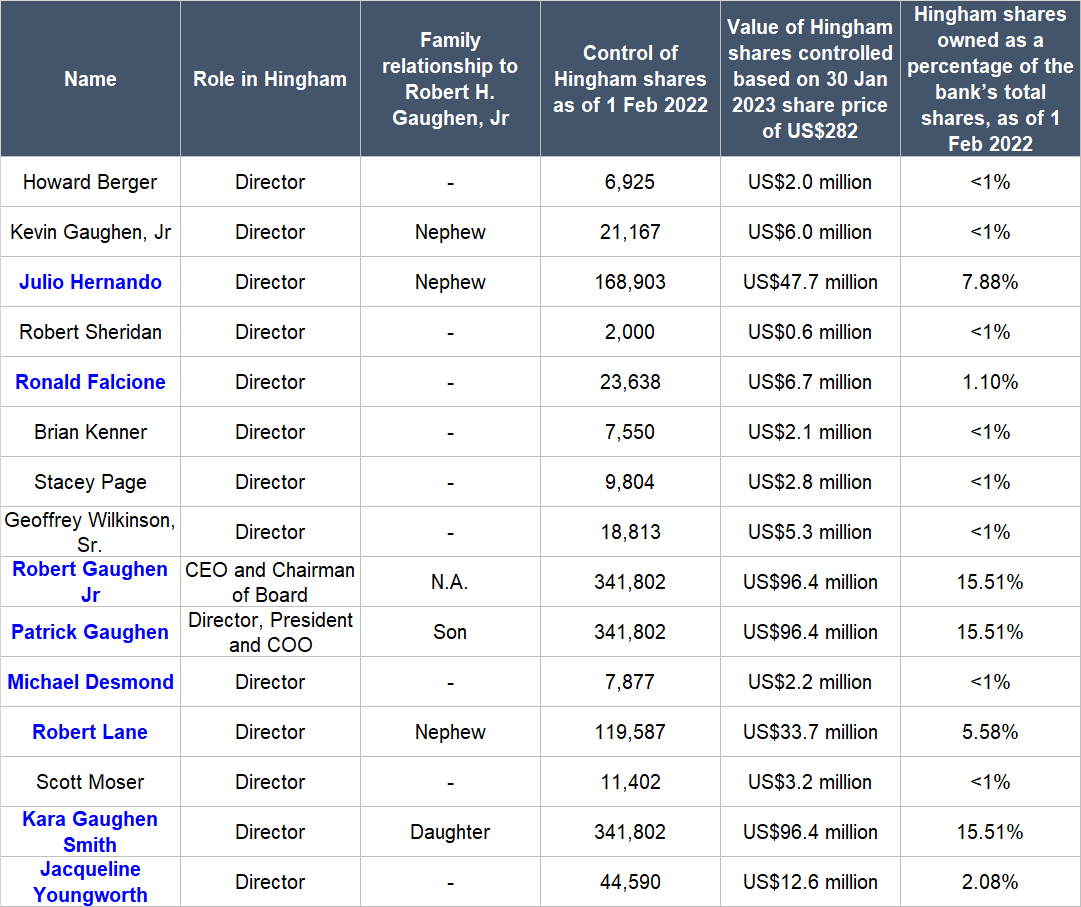

Another positive sign on management’s integrity is their skin in the game. As of 1 February 2022, Robert Gaughen Jr and his immediate family (this includes Patrick Gaughen) controlled 341,802 Hingham shares, or 15.5% of the bank’s total shares. This ownership stake is worth US$96.4 million based on Hingham’s 30 January 2023 share price of US$282 and significantly exceeds the direct compensation of the father-and-son duo at the bank’s helm.

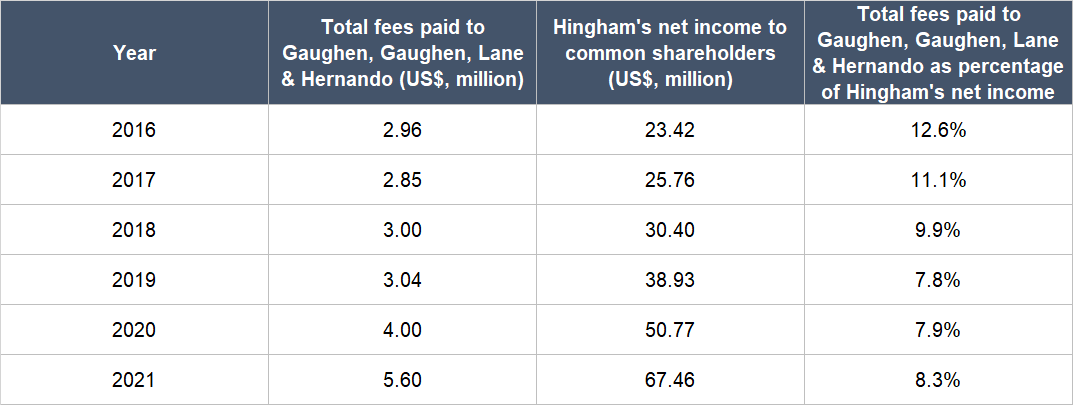

We do note that Hingham has engaged in related-party transactions for many years with a law firm named Gaughen, Gaughen, Lane & Hernando. The law firm is run by nephews of Robert Gaughen Jr who also happen to be directors of Hingham. The transactions in each year from 2016 to 2021 – they include legal fees that are related to Hingham’s loans and other corporate matters, and agency fees for title insurance – are shown in Table 5 below and they have accounted for up to 12.6% of Hingham’s annual net income.

Table 5; Source: Hingham annual reports

We are typically wary of high levels of related-party transactions. Their presence could indicate a nefarious situation of a company’s leaders enriching themselves at the expense of the company’s other shareholders. But on balance, we think Hingham’s related-party dealings do not reflect poorly on the integrity of the bank’s management team, given the bank’s excellent long-term history of growth that we will discuss in detail later in this, as well as in the “A proven ability to grow,” subsection.

On capability and innovation

We think Hingham’s management team is first-class when it comes to capability and innovation. Let’s discuss the capability angle first.

1994 was the first full-year where the bank was led by Robert Gaughen Jr as CEO. From then to 2022, Hingham’s book value per share – a key measure of a bank’s intrinsic value – grew in every single year and compounded at 11.6% annually, from US$8 to US$180. Over the same period, the bank was also profitable every year; in addition, its average return on equity (ROE) was a respectable 14.2%, and the lowest ROE achieved was 8.4% (in 2007). Hingham’s profitability and healthy ROEs in this timeframe is even more noteworthy when considering two things: (1) The bank had – and still has – heavy exposure to residential-related real estate lending; and (2) the time period covers the 2007-09 Great Financial Crisis. During the crisis, many American banks suffered financially and US house prices crashed. For perspective, while FDIC-insured US banks generated (ROEs) of 7.8%, 0.7%, and -0.7% in 2007, 2008, and 2009, Hingham’s ROEs were higher – at times materially so – at 8.4%, 11.1%, and 12.8%.

Table 6; Source: Hingham annual reports and FDIC data

The paragraph above also hints at the excellent work Gaughen Jr and his team have done at managing risks in Hingham’s lending business – if their risk management was poor, Hingham would not have been able to produce the ROEs that it has. What makes this clear is Table 6 above, which shows that Hingham’s net charge-offs (the percentage of the bank’s outstanding loans that are unlikely to be recovered) have been nearly non-existent since at least 2005, indicating minimal loan losses for the bank – and management’s superb control of lending risk – over that time period. Table 6 also demonstrates two other things: (1) Hingham’s net charge-offs have been extraordinarily low compared to the net charge-offs for real estate loans that are made by FDIC-insured US banks; and (2) Hingham’s leaders have an excellent aptitude for managing lending risk while not sacrificing the bank’s growth, since Hingham’s total assets has increased at a much faster pace than that of FDIC-insured banks.

Table 7; Source: Hingham annual reports

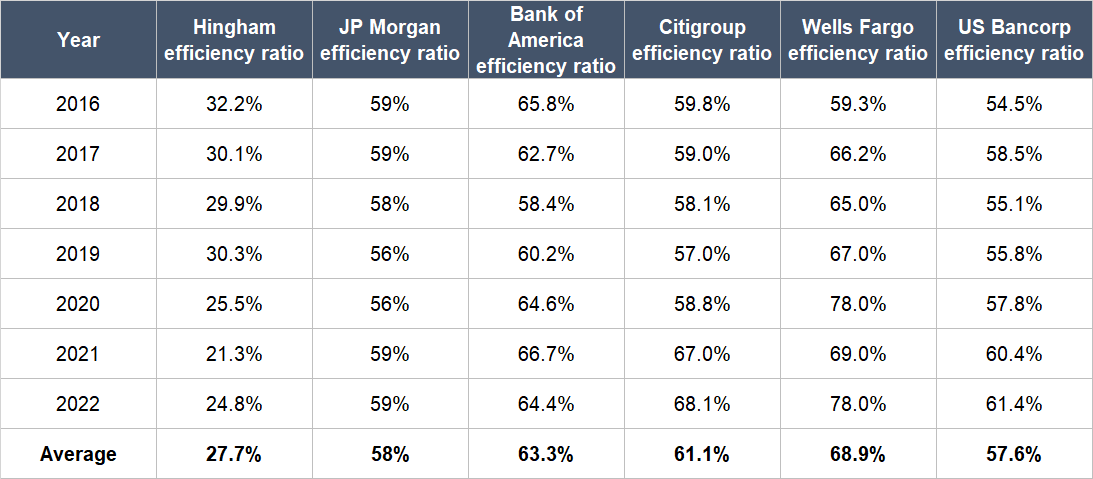

Another area where Hingham’s leaders stand out is in their management of costs. The efficiency ratio is a measure of a bank’s profitability and it is calculated by dividing a bank’s operating expenses by its revenue; the lower the ratio, the better. From 1994 (the first full-year of Robert Gaughen Jr’s tenure as Hingham’s CEO) to 2022, Hingham’s efficiency ratio has trended down and fallen substantially from 61.5% to 24.8%, as Table 7 above illustrates. It’s worth noting too that Hingham’s efficiency ratio is exceptional when compared to the US banking industry. For perspective, Hingham’s efficiency ratios from 2016 to 2022 are significantly lower than that of the US’s five largest banks by total assets at the moment (the quintet would be JPMorgan, Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, and US Bancorp). This is shown in Table 8 below.

Table 8; Source: Annual reports from Hingham and the other banks

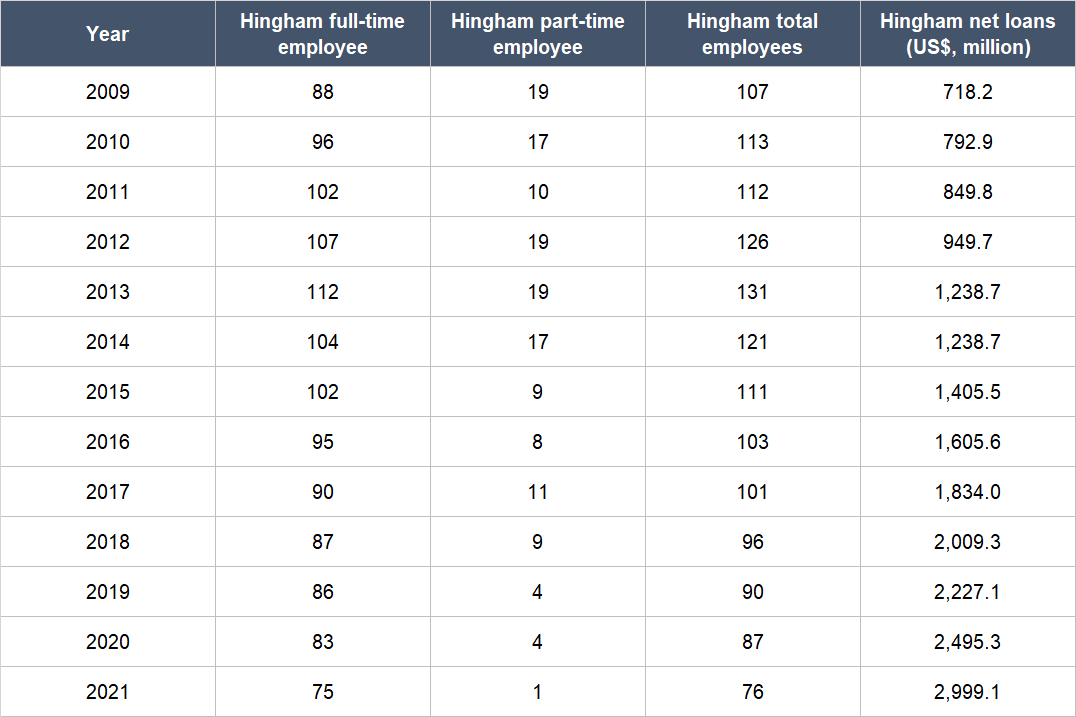

Related to the management of costs is Hingham’s change in headcount over time and this is another area that we found praiseworthy. Table 9 shows the bank’s total number of employees from 2009 to 2021, along with the growth of its net loans. Remarkably, Hingham shrunk its headcount by 42% from 2013 to 2021 while increasing its loans portfolio by 142%. We credit Hingham’s leaders for being able to consistently increase the efficiency and performance of the bank’s employees over the past decade or so.

Table 9; Source: Hingham annual reports

Coming to the innovation angle, we think Hingham’s management team excels here not because they have built fancy new lending products or cutting-edge banking technology. Rather, it’s the management team’s refreshingly idiosyncratic approach to both running the bank and investing the bank’s capital that has impressed us.

Hingham’s board of directors consists of 15 individuals, including Robert Gaughen Jr and Patrick Gaughen. Table 10 below shows who they are, along with (1) their familial relationships with Robert Gaughen Jr, if any, and (2) their ownership stakes in Hingham. Besides Robert Gaughen Jr and Patrick Gaughen, 12 other directors controlled stakes in Hingham, as of 1 February 2022, that are worth at least a few million dollars, based on the bank’s 30 January 2023 share price of US$282. In other words, nearly all of Hingham’s directors have skin in the game. It’s worth noting too that Robert Gaughen Jr’s three nephews who are directors of Hingham – Kevin Gaughen Jr, Julio Hernando, and Robert Lane (the trio also run the aforementioned law firm that has related-party transactions with Hingham) – also have significant ownership of the bank.

Table 10; Source: Hingham proxy statements (for some of the directors, the number of Hingham shares controlled includes Hingham shares that are owned by investment vehicles that are co-owned with other directors)

Within Hingham’s 15 directors are eight who belong in the Executive Committee, shown in blue in Table 10. The Executive Committee comprises primarily individuals who count their Hingham shares as a significant portion of their individual net worth. An important function of the Executive Committee is to review and approve Hingham’s commercial real estate, construction, and residential mortgage loans. To do so, the Executive Committee meets at least twice each month. Importantly, no lender or officer of Hingham has the authority to make such loans. Moreover, all loans that are above US$2.0 million, and all loans to borrowers with aggregate exposure of US$6.0 million, are subject to review and approval by all of Hingham’s directors. Consequently, all commercial real estate loans that Hingham has made have been reviewed and approved, on an individual credit basis, by some or all of Hingham’s directors. Hingham’s approach to managing lending risk was instituted when or shortly after Robert Gaughen Jr became CEO. It’s also a highly unusual approach among banks. But we appreciate it deeply because we think it’s a great way to ensure that a bank will be lending responsibly (we do note that this approach may have difficulty scaling further and thus could be a stumbling block to Hingham’s future growth; we’ll discuss this further in the “The risks involved” section of this article). Robert Gaughen Jr explained this during Hingham’s most recent annual shareholder’s meeting held in April 2022 (emphasis is ours):

“What we won’t change, and what I think has always been at the fore of our credit culture is credit decisions are made by the Executive Committee. The Executive Committee is comprised primarily of individuals with a significant portion of their net worth invested in this company. So they develop a certain level of expertise in terms of assessing properties. But having skin in the game is a very important and distinguishing feature between the little red line you couldn’t see on those net charge-offs for Hingham and the big blue line, which is an industry average [referring to slide 16 of Hingham’s presentation for the meeting]. So I’m sure there are folks that are more sophisticated in their credit analysis than we may be, but it appears that one of the factors that impacts net charge-offs may indeed be the fact that the people making decisions here are risking their own money to a certain extent, and I think that makes a big difference.”

Earlier in this thesis, in the “Company description” section, we mentioned that Hingham has a simple business. This has been the case since Robert Gaughen Jr became CEO, so this is by design. We also think it highlights a desirable quality of Hingham’s leaders: They have the ability to think and act independently. In other words, they can resist the institutional imperative. In Warren Buffett’s 1989 Berkshire Hathaway shareholders’ letter, he described the pernicious phenomenon as such (emphases are ours):

“My most surprising discovery: the overwhelming importance in business of an unseen force that we might call “the institutional imperative.” In business school, I was given no hint of the imperative’s existence and I did not intuitively understand it when I entered the business world. I thought then that decent, intelligent, and experienced managers would automatically make rational business decisions. But I learned over time that isn’t so. Instead, rationality frequently wilts when the institutional imperative comes into play.

For example: (1) As if governed by Newton’s First Law of Motion, an institution will resist any change in its current direction; (2) Just as work expands to fill available time, corporate projects or acquisitions will materialize to soak up available funds; (3) Any business craving of the leader, however foolish, will be quickly supported by detailed rate-of-return and strategic studies prepared by his troops; and (4) The behavior of peer companies, whether they are expanding, acquiring, setting executive compensation or whatever, will be mindlessly imitated.”

During Hingham’s aforementioned April 2022 annual shareholder’s meeting, a shareholder asked why the bank has avoided the wealth management business. For context, there are many banks in the USA that have sizeable wealth management income streams (JP Morgan, Bank of America, and Citigroup have them, for example). Patrick Gaughen’s response gives a great window into how Hingham’s leaders resist the institutional imperative and the mindset they have when it comes to not being distracted by what their peers are doing (emphases are ours):

“So there’s been a long, I think, fascination in the industry, particularly in small and medium-sized banks with the wealth management business. There are a number of other banks here in Boston that have long-standing trust departments. Sometimes it might appear in their name… And generally speaking, the attractiveness of that business to the banks that participate in it is the lack of a relationship with the fee streams that those businesses generate. Generally, it’s a fee that is based on assets under management. The lack of relationship between that fee stream and the net interest margin — and that is viewed as very, very attractive. And the idea is that regardless of the size of net interest margins, the direction of rates, the macroeconomic climate with respect to rates, those businesses will generate fee income. And one would think that it would be particularly attractive in geographies we operate in because the demographics are, when you look at Greater Boston and Washington and San Francisco, I think quite really, really affluent.

There are a couple of things about the business that I think are problems from our perspective. The first is we don’t know how to do it very well, which is probably the reason why we don’t do most of what we don’t do. And I think if most market participants were being honest, it would be the reason why most of them shouldn’t do it. It is a business where it is difficult to build sustainable competitive advantages. It is a business where it’s difficult to build sustainable positive operating leverage because of the ability of people in the business to move from bank to bank. And it’s a business where we think it’s historically the fees that have been collected on assets under management are probably going to be subject to significant secular pressure… I think that’s something we’ve thought a long time and it’s something we really see playing out in a way in which the investment management business today is operating.

It’s really quite ironic in some ways that there are a lot of banks that are interested in getting into asset management at a time when those fee structures are under such tremendous pressure. And so that’s something that I think has never been attractive to us, but there’s probably a lot of fancy words in there — the key thing is we don’t know how to do it really well. I tell a story when people ask me about wealth management about another bank. I’ll say in the New England region, a little bit vague about it, that for some period of time had some content front page of their website, talked about investment opportunity in China. They weren’t making direct investments. But it was more for people to use — [a phrase people use] is thought leadership. And I remember quite distinctly reading it and thinking, there is no way people at that bank, as nice as they are, have any kind of particular differentiated insight into investment in China. We certainly don’t.”

Hingham’s management team has also been very thoughtful when it comes to expanding the bank’s geographical footprint. Hingham, as we first discussed in the “Company description” section of this article, operates in only three markets in the USA: Massachusetts, WMA, and SFBA. The bank’s leaders believe that the most attractive markets for Hingham “are coastal, urban, gateway cities with substantial wealth, favorable demographics, substantial multifamily real estate, and consolidation among small and mid-sized banks.” Figure 3 is a map of the USA and illustrates the rough locations of Massachusetts, WMA, and SFBA – they are coastal cities. Furthermore, as we mentioned in the “Revenues that are small in relation to a large and/or growing market, or revenues that are large in a fast-growing market” sub-section of this article, these markets have a fast-growing number and high concentration of wealthy families.

Figure 3; Source: Google Maps

Both WMA and SFBA are relatively new markets for Hingham. The bank began lending in WMA only in November 2016 after studying and preparing to enter the market for two years. Hingham’s 2021 10-K has a description on why WMA looks attractive to the bank’s leaders and we think it beautifully demonstrates their thoughtful approach to exploring new markets:

“The Bank identified the WMA as an attractive opportunity for three reasons. First, the region has favorable economic characteristics that will support long-term investments in commercial real estate. It is the capital of the world’s largest economy, it is an international economic gateway, it has the highest household median income of any of the nation’s major metropolitan areas, and it has a relatively high concentration of young people. Second, the commercial real estate product in the market bears significant similarity to Boston, characterized by high density, urban infill development, transit-oriented multifamily, and scarcity imposed by land supply and restrictions on vertical development. Third, we believe that the banking market in Washington, D.C. has experienced a level of consolidation and disruption that has left smaller and mid-sized real estate investors underserved as compared to the Boston market. Although we are relatively new to this marketplace, we believe that our history as one of America’s oldest banks and our family management team provide stability and surety of execution that is valued by our customers.”

As for the SFBA market, Hingham only closed its first loans there in the fourth quarter of 2021. Similar to the way Hingham entered WMA, the bank started lending in SFBA only after researching the market for several years. The entrance also highlights the ability of Hingham’s leaders to seize lucky breaks. When the COVID-19 pandemic erupted, there were disruptions in SFBA’s real estate and banking markets that created an opening for Hingham. The bank’s management team thus decided to accelerate their plans to enter SFBA by a few years. Patrick Gaughen’s comments on the matter from the bank’s April 2022 annual shareholders’ meeting gives deeper insight:

“Long story short, we had San Francisco on the docket. And COVID-19 really pulled a lot of that forward. It had always been something where if it had been something prior to COVID, I think we would have thought it’s only 5 to 7 years in the future. COVID really provided us with a unique opportunity that we did not think would be likely to recur. And that opportunity was that the pandemic had a really outsized impact — it had a substantial impact on both credit and real estate markets today. They had an outsized impact on the markets in terms of the perception of the not just the sustainability of San Francisco’s success but the viability of the city.

So the number of headlines in The Wall Street Journal in 2020 and in early 2021, talking about the death of the Bay, you’d think that there was no one left and everyone had moved to Texas. And that was not a perspective that we shared. And our feeling was that — that psychological impact on the market, both from a real estate and credit perspective is something that we were prepared to exploit. We had already been doing the work, we had already put our eyes on the market, and it is really a matter of time to accelerate the work in engaging operational partners and conducting some of that diligence.”

In the “Company description” section of this article, we shared that Hingham has a portfolio of stocks that was worth US$55.0 million, or 14.2% of the bank’s book value of US$386.0 million, at the end of 2022. According to Hingham’s 2021 10-K, the bank’s leaders manage the portfolio to “produce superior returns on capital over a longer time horizon.” This is a trait we have not commonly seen in other banks. What particularly impressed us was Hingham’s investment process. The bank’s leaders focus on businesses “with strong returns on capital, owner-oriented management teams, good reinvestment opportunities or capital discipline, and reasonable valuations.” Management also “views [the holdings] as long-term partnership interests in operating companies.” Hingham’s stock holdings are “concentrated in a relatively small number of investments in the financial services and technology areas” and the payments companies Mastercard and Visa have been revealed in the past to be in the bank’s portfolio. But as far as we can tell, Hingham has not publicly shared details about its portfolio’s composition and performance. Nonetheless, the management team’s description of the way they invest still resonates with us because the core of the investment process is about identifying great businesses and patiently holding their shares.

4. Revenue streams that are recurring in nature, either through contracts or customer-behaviour

Hingham’s main business is in providing real-estate-related loans. This is a product that both companies and individuals should require on an ongoing basis (after all, companies and individuals need to buy and sell properties from time to time), so there should be high levels of recurring business activity for Hingham.

5. A proven ability to grow

In our explanation of this criterion, we mentioned that we’re looking for “big jumps in revenue, net profit, and free cash flow over time.” But for Hingham, our focus is on its book value per share as it is a key measure of a bank’s intrinsic value. The table below shows Hingham’s book value per share from 2005 to 2022, along with other important financial numbers. We chose 2005 as the starting point to observe how Hingham fared in the lead-up to, and during, the 2007-09 Great Financial Crisis.

Table 11; Source: Hingham annual reports and earnings updates

A few things to highlight from Hingham’s historical financials:

- Net interest income – the “revenue” earned by Hingham from its lending activities – grew in nearly every year from 2005 to 2022 and compounded at respectable annual rates of 11.0%, 10.8%, and 10.7% for the 2005-2022, 2012-2022, and 2017-2022 time periods, respectively.

- Total income – the “revenue” earned by the bank from its lending, stock market investing, and other business activities – also increased nearly every year from 2005 to 2022. But the annualised growth rates for the 2005-2022, 2012-2022, and 2017-2022 time periods – at 8.8%, 7.6%, and 4.9%, respectively – while acceptable, are significantly lower than that of Hingham’s net interest income. The key culprit here is the US$21.8 million decline in the value of Hingham’s portfolio of stocks in 2022. This ate into the bank’s total income.

- Net income attributable to Hingham’s common shareholders climbed over time, at an annual compounded rate of 11.2% from 2005 to 2022, 10.9% from 2012 to 2022, and 7.8% from 2017 to 2022. There was a sharp 44% fall in 2022 that was largely the result of the aforementioned decline in value of Hingham’s portfolio of stocks, and not because there was a significant deterioration in Hingham’s lending business.

- Net loans increased every year, and at healthy clips of 12.6% per year for the 2005-2022 time frame, 14.4% from 2012 to 2022, and 14.8% from 2017 to 2022. We do note that Hingham’s net loans to total deposits ratio was high for the entire time frame we’re looking at (it was always above 100%, sometimes significantly so) – this is a risk that we’ll discuss further in the “The risks involved” section of this article.

- Shareholders’ equity and book value per share both grew in each year from 2005 to 2022 and the growth rates are strong. Shareholders’ equity compounded at 13.0% annually for 2005-2022, 15.3% for 2012-2022 and 15.7% for 2017-2022. The selfsame growth rates for book value per share are nearly identical at 12.9%, 15.2%, and 15.5%. Hingham’s management team produced the growth in shareholders’ equity and book value per share without having the bank take on undue risk. This can be seen from Hingham’s total assets to shareholders’ equity ratio; it averaged at just 12.4 from 2005 to 2022 and never crossed above 14.2.

- Hingham’s return on equity was mostly in the mid-teens to high-teens percentage range and averaged at a highly respectable level of 14.4% for 2005-2022 and 16.0% for 2017-2022. The return on equity fell sharply in 2022, again, because of the aforementioned decline in value of Hingham’s portfolio of stocks during the year. Hingham also started reporting a core return on equity, which removes gains/losses from Hingham’s portfolio of stocks as well as gains from any sale of fixed assets, in 2014. Similar to the return on equity, Hingham’s core return on equity remained strong over time. The metric was in the mid-teens to high-teens range for the time period we’re studying and its average for 2014-2022 and 2017-2022 was 15.9% and 15.6%, respectively.

- Dilution was never a problem for Hingham as its weighted average diluted share count increased by only 4% in total from 2005 to 2022, which equates to an annualised growth rate of merely 0.2%.

6. A high likelihood of generating a strong and growing stream of free cash flow in the future

Being a bank, the concept of free cash flow is not as important for Hingham. What we’re concerned with is the future growth in its book value per share.

We think there’s a high likelihood that Hingham will grow its book value per share in the years ahead at a similar mid-teens percentage rate as it has historically achieved. The bank manages risk in its lending business in an exceptional manner and yet is still able to grow its portfolio of loans at an admirable rate over time. It also has an approach to stock market investing that we find sensible and think will work splendidly in the long run.

Valuation

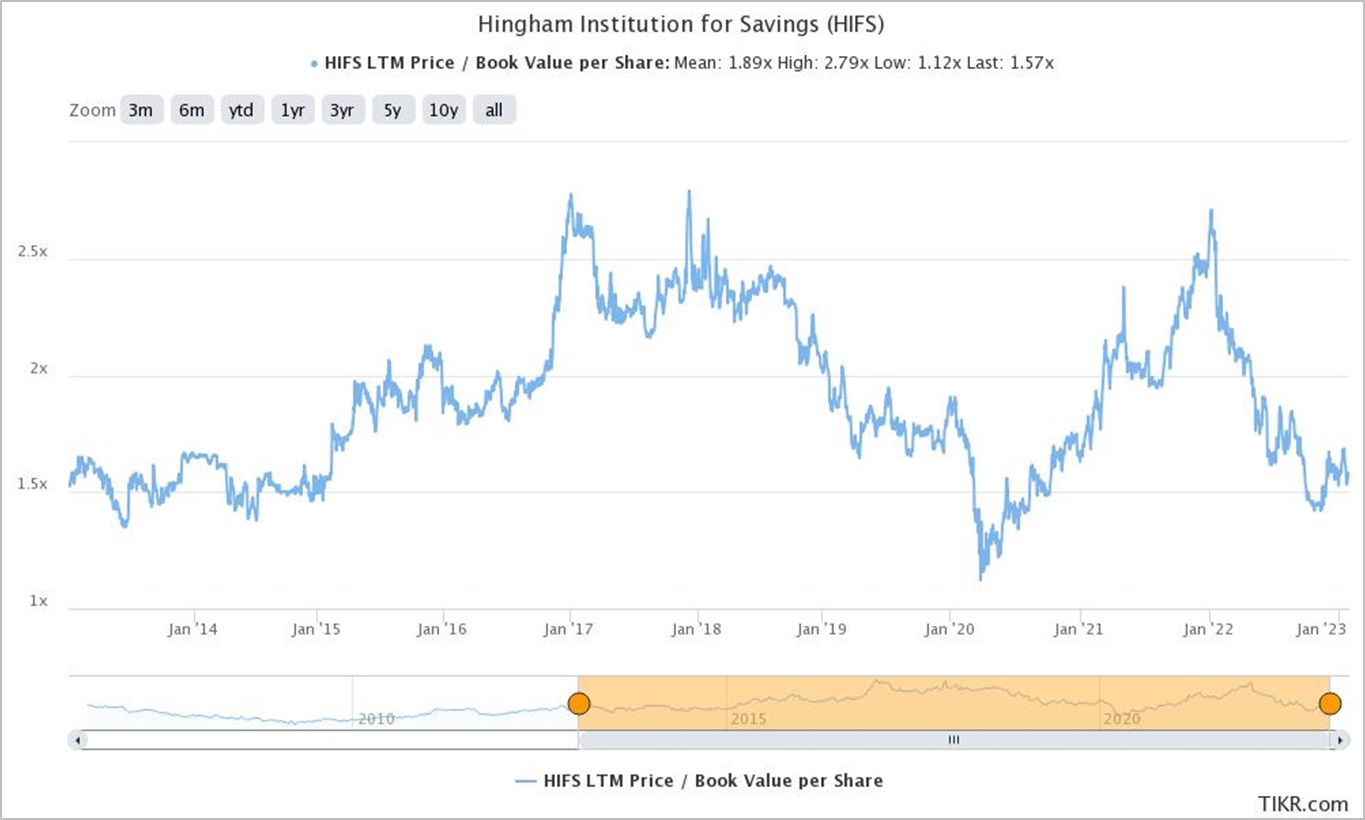

We like to keep things simple in the valuation process. In Hingham’s case, we think the price-to-book (P/B) ratio is a suitable gauge for the bank’s value. We completed the purchase of Hingham shares for Compounder Fund in late-December 2022. Our average purchase price was US$275 per share. At our average price and on the day we completed our purchase, Hingham’s shares had a trailing P/B ratio of 1.6. We think this is a reasonable valuation for a bank that could likely compound its book value per share at a mid-teens rate in the years ahead. Moreover, the P/B ratio of 1.6 is near the low-end of where the ratio has been over the past decade ended 2022. Figure 4 below shows Hingham’s P/B ratio from the beginning of 2013 to the end of January 2023:

Figure 4; Source: Tikr

For perspective, Hingham carried a trailing P/B ratio of 1.6 at the 30 January 2023 share price of US$282.

The risks involved

We see a few key risks that could harm our investment in Hingham.

The first risk involves the current state of the US housing market. Hingham’s core business, as we’ve already discussed, is to lend against properties in the USA that are used for residential purposes. This means the bank has heavy exposure to the housing market in the country. Right now, this market is weak. Figure 5 below shows that total existing home sales in the USA had declined throughout 2022 and is now even lower than the COVID-19 trough. Meanwhile, Figure 6 shows US housing starts – the total number of single family homes that began construction in a month – over the same period and it’s a similar picture: Housing starts have been declining over the course of 2022. There’s a possibility that both numbers have more room to fall, since US mortgage rates rose sharply in 2022, as shown in Figure 7, which plots the average interest rate for 30-year fixed-rate mortgages in the USA over the past decade.

Figure 5; Source: National Realtors Association

Figure 6; Source: Ycharts

Figure 7; Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

If existing home sales and housing starts in the USA continue their downward trend, Hingham’s business could be hurt. What gives us comfort is the bank’s business performance during the 2007-09 Great Financial Crisis. Back then, even when the US housing market was in shambles, Hingham’s net loans, net interest income, net income to shareholders, and book value per share all grew (see Table 11 and the financial numbers for 2007-2009). It’s worth noting too that Hingham was operating only in Massachusetts during the crisis; today, the bank also has a presence in WMA and SFBA, giving it more avenues to find growth.

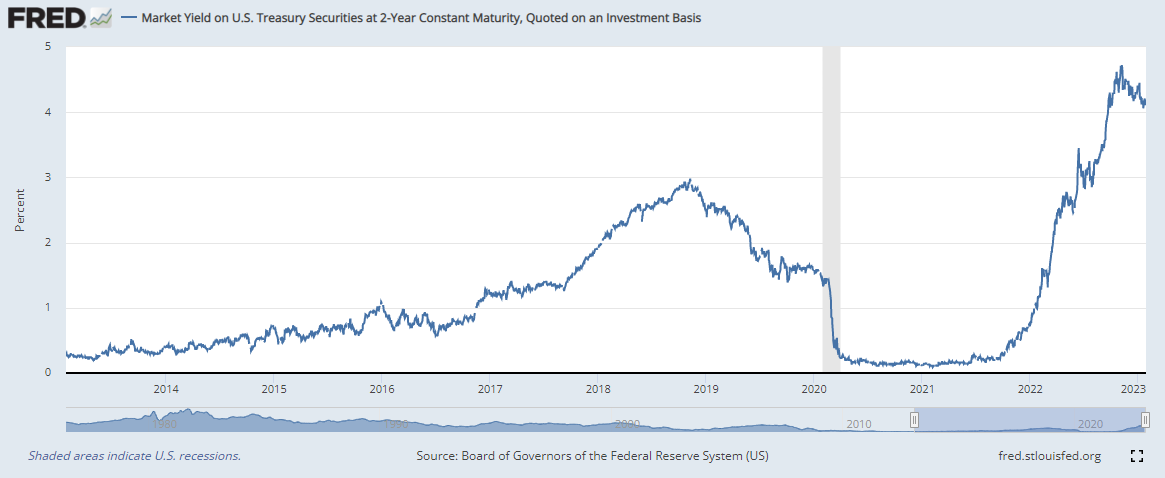

Another risk we’re watching is related to the interest rate environment in the USA. Hingham has, for a long time, maintained what’s known as a liability-sensitive balance sheet, where sharp increases in short-term interest rates would have a much larger impact on the bank’s cost of funding (the interest it needs to pay on its deposits and other sources of capital) compared to the interest it earns on its loans. Short-term rates in the US rose rapidly in 2022. For perspective, the federal funds rate, which is the key benchmark interest rate controlled by the US’s central bank, the Federal Reserve, was raised at a historically fast pace during the year, as shown in Figure 8 below. It’s a similar story for the US 2-year Treasury yield – Figure 9, which shows the yield for US 2-year Treasuries over the past decade, highlights a sharp rise in the yield in 2022.

Figure 8; Source: Satista

Figure 9; Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

The rapid rise in short-term rates has left a mark on Hingham’s results. Hingham enjoyed a strong 25.8% increase in total interest and dividend income from US$110.5 million in 2021 to US$139.0 million in 2022. But the bank’s net interest income grew by only 3.6% (from US$102.5 million to US$106.1 million) because its interest expense ballooned (from US$8.0 million to US$32.9 million). But the way Hingham’s leaders are managing this risk looks sensible to us. Here’s what Patrick Gaughen said on the topic during the bank’s April 2022 annual shareholder’s meeting (emphases are ours):

“And I think it’s important to think and maybe describe the way that I think about this is that we’re not protecting profits in any given period. We’re thinking about how to maximize returns on equity on a per share basis over a long time period, which means that there are probably periods where we earn, as I said earlier, outsized returns relative to that long-term trend. And then periods where we earn what are perfectly satisfactory returns. Looking back over history, with 1 year, 2 years exceptions, double-digit returns on equity. So it’s satisfactory, but it’s not 20% or 21%.

And the choices that we’ve made from a structural perspective about the business mean that we need to live with both sides of that trade as it occurs. But over the long term, there are things we can do to offset that. So the first thing we’re always focused on regardless of the level and the direction of rates is establishing new relationships with strong borrowers, deepening the relationships that we have with customers that we already have in the business. Because over time, those relationships as the shape of curve changes, those relationships are going to be the relationships that give us the opportunity to source an increasing volume of high quality assets. And those are the relationships that are going to form the core of the noninterest-bearing deposits to allow us to earn those spreads. And so that’s true regardless of the direction of rates.

And the second thing, which is implied in the first, really being focused on not losing money. And this is really important in periods when rates are falling, because that’s often a period where there might be some lack of discipline in the market. There are periods certainly in the last 10 to 15 years, where we’ve seen that’s the case. And it can be true when rates are rising — we spent some time talking in the past about why bankers have misunderstandings about the S&L crisis [Savings and Loans crisis] in the ’80s, with respect to how a lot of those banks failed. And that was in periods when rates were rising, there were a lot of S&Ls that looked for assets that had yields that would offset the rising price of their liabilities, and those assets had risks that the S&Ls did not appreciate. Rather than accepting tighter margins through those periods where there were flatter curves, they resisted. They tried to protect those profits. And in doing so, they put assets on the balance sheet that when your capital’s levered 10x or 11x or 12x or 13x to 1 — they put assets on the balance sheet that went under.

I would say that I don’t think about protecting profits of the bank as they do, if you think about what that performance would be over a multiyear period. And implied in that is the idea that over time, there will be duration premium, which is to say that longer-term money will be more expensive than shorter-term money. So periods of inversion, flat curves, although painful for us, are in the scheme of things, likely to be temporary.”

A third risk we’re keeping an eye on is Hingham’s approach to managing lending risk. In the “A management team with integrity, capability, and an innovative mindset” sub-section of this article, we shared that Hingham’s loans can only be approved by members of its board of directors. We also mentioned that this approach – which has been a long-standing practice at Hingham – may “have difficulty scaling further and thus could be a stumbling block to Hingham’s future growth.” We’ll be watching for signs of the process cracking under more weight. But the good things here are that Hingham has (1) managed to produce admirable long-term growth in its business, and (2) improved the logistics for its loan-approval process over time. During Hingham’s April 2021 annual shareholder’s meeting, Patrick Gaughen also shared an amusing yet enlightening story about Hingham’s loan approval process that is related to our discussion here (emphasis is ours):

“[Patrick Gaughen:] I wasn’t there for it, but my dad has told and maybe now he could tell the story of a lender that either interviewed with us or may have worked for us briefly dad, who believed that we would never be able to grow using the system.

[Robert Gaughen Jr] Yes, that was back in approximately 1995. And that particular lender, we were at the time, about US$175 million in total assets. And that lender assured me that we could not grow at all with this business of having a committee of directors, looking at our commercial real estate loans every two weeks and approving them. He wanted loan authority and assured me that we just couldn’t move forward unless he was given that authority, but of course he was never given that authority. And his suggestion was obviously proven to be an inaccurate one. And I know you’ve mentioned to me, some significantly larger banks – that multiples of our size, many multiples – who on loans of a significant size, have had at least one of their executive committee directors, putting actual eyes on those properties before the credits are approved. So I fully agree with you, Patrick, that it is very deeply ingrained in our culture. And while it may need to be modified in terms of loan amounts going to the Board of Directors, I don’t see any change in the foreseeable future in the executive committee’s role in reviewing every single commercial real estate loan.”

Another key risk we see deals with Hingham’s high net loans to total deposits ratio (see Table 11 above). The danger with a high ratio is that it causes a bank to be exposed to liquidity risk, where a bank has difficulty meeting its short-term financial obligations. In a typical banking business, a bank would accept deposits from depositors and in turn loan the deposits to borrowers. These deposits are considered to be a bank’s short-term financial obligations, since depositors are typically allowed to withdraw their deposits on short notice. The loans, however, often cannot be recalled quickly. If large numbers of a bank’s depositors start asking for their deposits back, that’s when liquidity risk could erupt for the bank. The risk is heightened if a bank’s loan portfolio significantly outweighs the amount of its deposits. In this scenario – which Hingham is in, given its net loans to total deposits ratio of 146% currently, as shown in Table 11 – there’s only a thin buffer for a bank to absorb any loss of deposits. But we find comfort in a few things:

- Hingham also borrows from the Federal Home Loan Bank of Boston (FHLB) to fund its loans and it has done so for decades, even before the Gaughens assumed leadership of Hingham. The FHLB belongs to the Federal Home Loan Bank System, which is sponsored by the US government and comprises 11 Federal Home Loan banks and 6,800 member financial institutions. The mission of all Federal Home Loan Banks is to provide their members (banks such as Hingham) with reliable funding so that the members can finance the housing and other needs of their communities. With this as a backdrop, Hingham has a stable source of capital from the FHLB (the borrowings from the FHLB are known as advances) with which it can lend to borrowers. At the end of 2022, Hingham’s net loans of US$3.66 billion was a tad lower than the sum of its total deposits and FHLB advances (US$2.51 billion and US$1.28 billion); this helps reduce Hingham’s exposure to liquidity risk, in our opinion. Hingham has materially increased its FHLB advances over time (from just US$211.8 million in 2005 to US$402.5 million in 2015 and to US$1.28 billion today), so the bank should be able to continue to tap on the FHLB, whenever it needs to, to grow its loans portfolio in the future.

- Hingham’s deposits grew in each year from 2005 to 2009. This is noteworthy because those were the years that led up to and were in the Great Financial Crisis, a period that was extremely stressful for banks. Moreover, Hingham was solidly profitable in each of those years, despite having a high net loans to total deposits ratio in each of them. These strongly suggest that Hingham did not face any problems related to fleeing-depositors. The strong historical performance of Hingham’s management team with respect to holding onto the bank’s deposit base in a time of turmoil gives us confidence that the bank’s leaders would likely be able to safely steer the bank through any troubled-waters in the years ahead.

The last risk we’re paying attention to is key-man risk. Hingham’s CEO, Robert Gaughen Jr, is already 74 this year. The good thing is there appears to be a clear succession plan in place with the promotion of Patrick Gaughen – who’s only 42 – to President and Chief Operating Officer in 2018. The younger Gaughen has been given plenty of air-time to speak and answer questions during Hingham’s annual shareholders’ meeting since 2020, at least. From our review of his comments (and we’ve shared snippets earlier in this article), we think he’s very much in the same mould as his father when it comes to managing a bank. Nonetheless, we’ll be watching the situation whenever Robert Gaughen Jr passes his baton to Hingham’s next leader.

Summary and allocation commentary

To sum up Hingham, the bank has:

- A massive market to grow into, in the form of the US banking industry’s US$3.1 trillion worth of real-estate related loans

- A robust balance sheet with its total assets to shareholders’ equity ratio of 10.9 at the end of 2022

- A leadership team with skin-in-the-game, a reasonable compensation plan, unique mindsets towards managing lending risk and stock marketing investing, and a long-term track record of excellent execution

- Recurring business from the nature of the real-estate-related loans it makes

- A long history of respectable growth in book value per share while keeping risks low

- A good chance of being able to continue growing its book value per share at a decent clip over time

As it is with every company, there are risks to note for Hingham. The main ones we’re watching include: The current downturn in the US housing market; the recent sharp rise in short-term US interest rates; the possibility that Hingham’s idiosyncratic way of managing lending risk may not be able to scale further; liquidity risk stemming from the bank’s high net loans to total deposits ratio; and key-man risk.

After weighing the pros and cons, we decided to initiate a position of around 1.5% in Hingham in late-December 2022. Our initial position in Hingham can be considered to be a mid-sized allocation. We appreciate all the strengths we see in Hingham’s business, especially the management team’s unconventional yet sensible mindset toward the business of banking. But we also want to further observe how Hingham’s business would fare if the US housing market continues its downward march and/or short-term US interest rates carry on rising rapidly.

And here’s an important disclaimer: None of the information or analysis presented is intended to form the basis for any offer or recommendation; they are merely our thoughts that we want to share. Of all other companies mentioned in this article, Compounder Fund only owns shares in Hingham. Holdings are subject to change at any time.