Economic Crashes & Stock Market Crashes - 19 May 2020

One of the most confusing things in the world of finance at the moment is the rapid recovery in many stock markets around the world after the sharp fall in February and March this year.

For instance, in the US, the S&P 500 has bounced 28% higher (as of 15 May 2020) from the 23 March 2020 low after suffering a historically steep decline of more than 30% from the 19 February 2020 high. In Singapore, the Straits Times Index has gained 13% (as of 15 May 2020) from its low after falling by 32% from its peak this year in January.

The steep declines in stock prices have happened against the backdrop of a sharp contraction in economic activity in the US and many other countries because of COVID-19. Based on news articles, blog posts, and comments on internet forums that I’m reading, many market participants are perplexed. They look at the horrible state of the US and global economy, and what stocks have done since late March, and they wonder: What’s up with the disconnect between Main Street and Wall Street? Are stocks due for another huge crash?

I don’t know. And I don’t think anyone does either. But I do know something: There was at least one instance in the past when stocks did fine even when the economy fell apart.

A few days ago, I chanced upon a fascinating academic report, written in December 1908, on the Panic of 1907 in the US. The Panic of 1907 flared up in October of the year. It does not seem to be widely remembered now, but it had a huge impact. In fact, the Panic of 1907 was one of the key motivations behind the US government’s decision to set up the Federal Reserve (the US’s central bank) in 1913.

I picked up three sets of passages from the report that showed the bleak economic conditions in the US back then during the Panic of 1907.

This is the first set (emphasis is mine):

“Was the panic of 1907 what economists call a commercial panic, an economic crisis of the first magnitude?…

… The panic of 1907 was a panic of the first magnitude, and will be so classed in future economic history…

… The characteristics which distinguish a panic of that character from those smaller financial convulsions and industrial set-backs which are of constant occurrence on speculative markets, are five in number:

First, a credit crisis so acute as to involve the holding back of payment of cash by banks to depositors, and the momen- tary suspension of practically all credit facilities.

Second, the general hoarding of money by individuals, through withdrawal of great sums of cash from banks, thereby depleting bank reserves, involving runs of depositors on banks, and, in this country, bringing about an actual premium on currency.

Third, such financial helplessness, in the country at large, that gold has to be bought or borrowed instantly in huge quantity from other countries, and that emergency expedients have to be adopted to provide the necessary medium of exchange for ordinary business.

Fourth, the shutting down of manufacturing enterprises, suddenly and on a large scale, chiefly because of absolute inability to get credit, but partly also because of fear that demand from consumers will suddenly disap- pear.

Fifth, fulfilment of this last misgiving, in the shape of abrupt disappearance of the buying demand through- out the country, this particular phenomenon being pro- longed through a period of months and sometimes years…

…For the panic of 1907 displayed not one or two of the characteristic phenomena just set forth, but all of them…

Here’s the second set:

“During the first ten months of 1908, our [referring to the US] merchandise import trade decreased [US]$319,000,000 from 1907, or no less than 26 per cent, and even our exports, despite enormous shipment of wheat to meet Europe’s shortage, fell off US$109,000,000.”

This is the third set, which laid bare the stunning declines in industrial activity in the US during the crisis:

“The truth regarding the industrial history of 1908 is that reaction in trade, consumption, and production, after the panic of 1907, was so extraordinarily violent that violent recovery was possible without in any way restoring the actual status quo.

At the opening of the year, business in many lines of industry was barely 28 per cent of the volume of the year before: by mid- summer it was still only 50 per cent of 1907; yet this was astonishingly rapid increase over the January record. Output of the country’s iron furnaces on January 1 was only 45 per cent of January, 1907: on November 1 it was 74 per cent of the year before; yet on September 30 the unfilled orders on hand, reported by the great United States Steel Corporation, were only 43 per cent of what were reported at that date in the “boom year” 1906.”

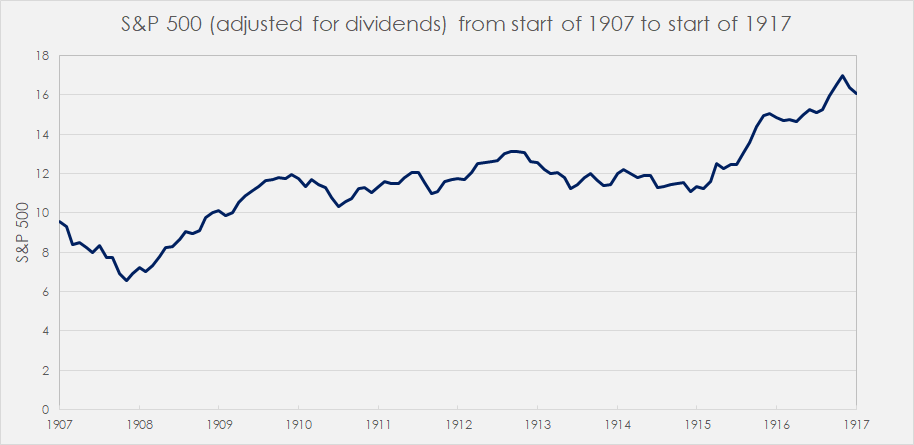

Let’s now look at how the US stock market did from the start of 1907 to 1917, using data from economist Robert Shiller.

Source: Robert Shiller; my calculations

The US market fell for most of 1907. It bottomed in November 1907 after a 32% decline from January. It then started climbing rapidly in December 1907 and throughout 1908 – and it never looked back for the next nine years. Earlier, we saw just how horrible economic conditions were in the US for most of 1908. Yes, there was an improvement as the year progressed, but economic output toward the end of 1908 was still significantly lower than in 1907.

April-May 2020 is not the first time that we’re seeing an apparent disconnect between Wall Street and Main Street. I don’t think it will be the last time we see something like this too.

Nothing in this article should be seen as me knowing what’s going to happen to stocks next. I have no idea. I’m just simply trying to provide more context about what we’re currently experiencing together. The market – as short-sighted as it can be on occasions – can at times look pretty far out ahead. It seemed to do so in 1907 and 1908, and it might be doing the same thing again today.